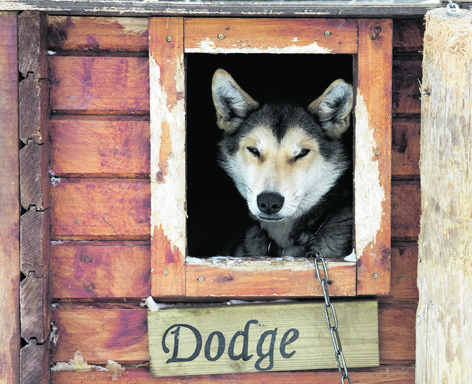

“Most people have forgotten how to look after themselves”, sighs Norwegian Eirik Nilsen as he harnesses up six of his prize cross-breed Alaskan huskies for an afternoon sled ride through the freshly laid snow.

Owner of the Holmen Husky dog farm and an experienced musher who’s competed in Europe’s longest dog sledding race, the Finnmarkrace, 14 times, Eirik is – by contrast – someone who does know how to survive in the great outdoors.

Recalling the difficulty I’d had trying to ignite the wood burner in my swish, heated Sami lavvo tent (a bit like a North American tipi) the previous night, I shudder at my own incompetence. I’m exactly the sort of paralysed urbanite Eirik shuns.

But when faced with the frozen wilderness of Finnmark, Norway’s northernmost and least populated county, it’s fair to assume most city dwellers would feel out of their depth.

A 10-minute drive from Alta, the area’s main city, Holmen Husky is one of several places where tourists can learn how to grapple with extremes of nature, while enjoying the peace and solitude of the

Arctic Circle.

As the weather warms up – from April onwards – Eirik runs multi-day dog sledding expeditions, camping along the way. I’m happy, though, with the 15km tour offered in winter, using it as a warm-up for the real purpose of my visit – a chance to see the northern lights.

As the weather warms up – from April onwards – Eirik runs multi-day dog sledding expeditions, camping along the way. I’m happy, though, with the 15km tour offered in winter, using it as a warm-up for the real purpose of my visit – a chance to see the northern lights.

Sitting beneath the aurora ‘oval’, where activity is generally concentrated, and with a good track record for clear skies, Alta is a popular spot for northern lights hunters. Kristian Birkeland, a Norwegian scientist who developed groundbreaking theories about the aurora, even chose to build an observatory close by in the late 19th century.

Smaller than northern lights capital Tromso, and attracting less tourists, Alta feels just that little bit more off the beaten track.

Hurtling through snow-dusted forests, sunlight streaming through regimented rows of spindly, upright pine trees, civilisation feels very far behind me. My dog team speeds onward like a runaway freight train, and I end up heaving my full body weight onto the metal brake, to try and slow them down.

Very soon, my accelerated heartbeat thuds in time with their heavy panting as I anticipate a crash at every undulating rise and fall in the trail. But when we coast along it’s euphoric, and I feel as if I’m flying through the air.

Eirik’s words echo across the icy valley: “Always make sure the dogs know who’s in control.”

Eirik’s words echo across the icy valley: “Always make sure the dogs know who’s in control.”

As enjoyable as the ride is, I’m quite relieved to relinquish command and head to Holmen Husky’s hospitable ‘barn’, where dinner is served at a communal table and beers are readily available from the family-size fridge.

After eating, I slope off to my lavvo, kept warm by a wood burner (lit by someone else if you, too, lack fire-making skills), to wait for the northern lights to show up. The sound of 80 barking dogs ensures I don’t fall asleep too early, but unfortunately, the aurora fails to materialise. Instead, I settle into my cosy tipi-style tent -so toasty that at some point, I have to fling aside my blankets in a sweat.

It’s a thought I try to hold onto when I arrive at my next destination, the Sorrisniva Igloo Hotel, a 20-minute drive from Alta.

Every year, when the ice is good enough, a team works for five weeks to build a 30-room property with a bar, and even a wedding chapel, with pews draped in reindeer skins.

The property is set alongside the frozen Alta River, where I venture in a second attempt to catch the aurora, making sure I steer clear of cracks in the ice, where water surges violently to the surface.

The property is set alongside the frozen Alta River, where I venture in a second attempt to catch the aurora, making sure I steer clear of cracks in the ice, where water surges violently to the surface.

This time I’m lucky, and although the burst of activity is short, it is intense: swirling green strands coil and ripple as if a cavalcade of cosmic horsemen are frantically cracking their whips before galloping into the night.

Satisfied with the display, I seek comfort in the hotel’s permanent wooden structure, which houses a restaurant, log fire, hot showers and sauna. But soon, I have to face the inevitable – a night spent sleeping in the deep freeze.

Satisfied with the display, I seek comfort in the hotel’s permanent wooden structure, which houses a restaurant, log fire, hot showers and sauna. But soon, I have to face the inevitable – a night spent sleeping in the deep freeze.

Grabbing a thermal sleeping bag, I battle through a snow shower to reach the grand igloo, where intricate ice carvings of reindeer-pulled sleighs and forbidding Vikings fill the hallway. The temperature inside is -7 degrees, and I can already see clouds of condensation forming as I breathe.

Electric lights illuminate a faux fireplace, which fails to evoke any sensation of warmth, and my bed for the night is a block of ice covered in reindeer hides, which reek of dead animal.

Some past visitors claim to have had the “best night’s sleep ever” here, but after seven hours of mimicking a woodlouse, curling into a tight ball, I conclude they must have either been drunk or lying.

One night is an adventure; two nights would be endurance.

After a 7am sauna and hot breakfast though, the igloo becomes a more hospitable place. I muster enough energy to snowshoe along the frozen river and to go tobogganing down the steep sides of a valley, seated on a plastic sack.

After 10 attempts, my shoes are full of snow and my clothes soaking wet, but I’m not especially bothered. After a quick stint – fully dressed – in the sauna, they soon dry out.

Making use of all your resources is, after all, the key to survival in the wilderness. Contrary to Eirik’s belief, some urbanites do know how to look after themselves.

TRAVEL FACTS

Sarah Marshall was a guest of the Visit Norway (www.visitnorway.com) and the Northern Norway Tourist Board (www.nordnorge.com/en).

An overnight stay at Holmen Husky (www.holmenhusky.no) with dog sled ride, breakfast, dinner and transport from Alta costs £227pp (two sharing).

An overnight stay at the Sorrisniva Igloo Hotel (www.sorrisniva.no) with breakfast costs £171pp (two sharing).