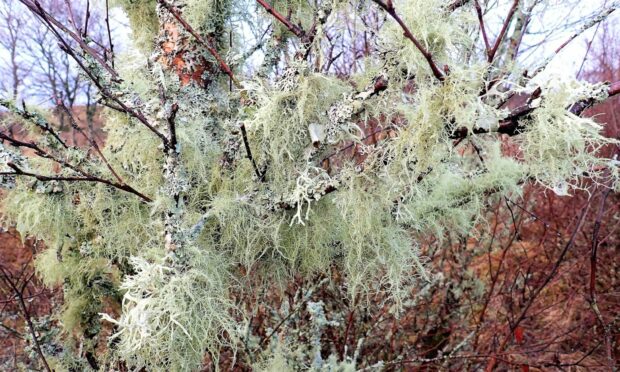

It was a natural adornment of extraordinary lushness – a thick and copious covering of grey-dripped lichens that bedecked a small birch by the edge of woodland in the Trossachs.

I brushed my hands across this thick flush of unusual life, marvelling at the intricate shape and form of these magical lichens.

The birch was covered from top to toe in a powderpuff of grey and subtle greens, a wondrous silvery shroud that glinted under the soft glow of the low winter sun.

Hanging in thick tassels

The predominate type was ‘old man’s beard’, which hung in thick tassels from the birch branches, but there were several other more compact lichens, one of which I identified as a species known as monk’s-hood lichen.

As I examined these lichens, it was difficult to get my head around their complex and intriguing biology.

Rather than one organism, lichens consist of a symbiotic association of fungi and algae, or sometimes with cyanobacteria, which is a type of blue-green algae.

These composite organisms work in a mutually beneficial partnership where the fungus gleans nourishment from the photosynthetic properties of the alga (or cyanobacterium), while the fungus provides protective shelter for the alga, ensuring optimal living conditions.

In effect, lichens are mini ecosystems.

Beauty and variety

Lichens exhibit infinite beauty and variety in form, and a short while after encountering this lichen adorned birch, I found another tree encrusted with a yellowish lichen on one of its branches, which I tentatively identified as golden shield lichen or yellow scale, although I might have been wrong.

Lichens are a bedrock of the natural environment and even occur in some of our harshest environments such as the arctic tundra, mountain tops, hot dry deserts and rocky coasts.

But it is in woodland where they come into their own, benefiting wildlife by providing shelter for invertebrates, which in turn are feasted upon a range of other creatures, including birds such as tits and treecreepers.

Many birds use lichens as nesting material during spring and summer.

Lichens are also useful indicators of air quality, thriving in places where the atmosphere is clean and pure.

Carpet of moss

As I descended into thick woodland by a rocky gorge, I stopped to examine an old oak, which was covered in a verdant carpet of moss.

As with lichens, moss forms and important refuge for invertebrates, a place to shelter and breed.

A profusion of polypody ferns also gained tenure on this oak, providing the aura of a tropical rainforest where abundant epiphytes cling to trees.

A green woodpecker yodelled in the distance, which reinforced the rainforest comparison, as its repetitive call had a lyrical stridency that would not have felt out of place in more tropical climes.

Yet, the air was cool and damp, with a hint of frost.

As I strode for home, a coal tit busied itself on the bough of another gnarled oak, its thin bill eagerly probing the moss and lichen for the hidden bounty of invertebrates that lay within this enchanting Trossachs rainforest.