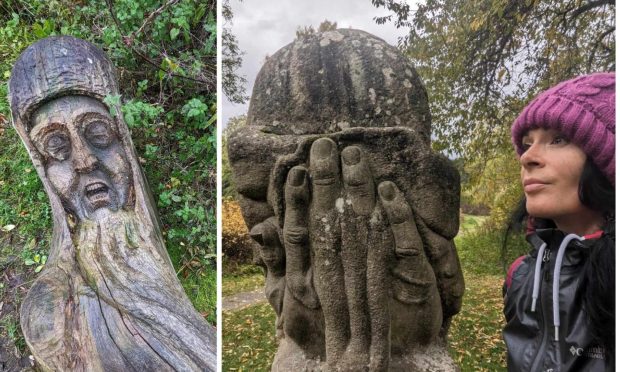

A wooden face with sunken eyes emits a soul-stirring, silent scream.

Nearby, a rotting, insect and fungi-ridden figure lies on the ground, grimacing in horror.

Walking through Frank Bruce’s sculpture trail is a surreal and haunting experience – and one that will stay with you for quite some time.

Hidden deep in woodland near Feshiebridge – about eight miles from Aviemore – many of the sculptures have toppled over or been laid to rest on the forest floor.

Most are slowly decaying, and returning to the earth – which is exactly what Bruce intended.

Nature cycle of birth, life and death

The Aberdeenshire-born sculptor always anticipated a relatively short life-span for his work – his vision was to allow his pieces to endure the natural cycle of birth, life and death.

Huge works of art carved from timber and stone, vividly depicting a wide range of human emotions, are dotted throughout the forest and inside a walled garden.

None of the figures are smiling – most appear to be suffering intensely or deep in thought.

To describe it as the stuff of nightmares would be to simplify Bruce’s work, but truth be told, I wouldn’t fancy wandering along the trail in the dead of night.

Open-air art gallery

The little-known open-air art gallery opened in 2007 to showcase the acclaimed self-taught sculptor’s work.

It was a wet, blustery morning when I rocked up there recently, and autumn leaves were being violently ripped from the trees.

A short stroll from the Forestry Commission car park west of Feshiebridge brought me to the winding wheelchair-accessible trail.

The Archetype

The first sculpture, The Archetype, was lying prone on its side and gazing to the heavens.

It had once stood sentinel, keeping watch over the forest, and despite its change in position, it retains an air of wisdom and power.

The Walker, an enormous, eight metre sculpture, has also tumbled to the ground, or been moved there for health and safety reasons.

This abstract piece, a bit like an upturned tree, clutches a walking pole and appears to be taking a giant stride, although it’s now flat on its back and sprawled out like a drunken triffid.

Inspired by Rabbie Burns

The Man’s a Gowd, meanwhile, inspired by Bruce’s love of Robert Burns, features a belted knight looking with contempt at a workman.

Both sport a skull – a symbol of mortality – over their heads, indicating that we all return to the dust, no matter who we are, whether nobility or working class.

Creepy

I’m completely creeped out by Inner Man. This remains upright, and boasts a rather terrifying figure with a crack through his face.

Inside his wooden “body”, there’s a sad, or perhaps, morose-looking face.

The interpretation board beside the work says: “You can see my outward physical appearance. My inner self is far more difficult to discern”.

Third World

Bruce was fascinated by our relationship with the developing world, and one work in particular, Third World, shows developed-world men blinded to the suffering and condition of the developing world.

Another, Two Patriots, uses the division of the tree trunk to make his point – that in war, we fight ourselves, and that we rely on patriots to create suffering.

In Bruce’s words: “To make a war a patriot on both sides is needed. A winner and a loser. Eighty per cent of casualties are civilians. Hitler needed patriots”.

Horror and sadness

The Onlooker, meanwhile, features two heads – one looking in horror at the conflict of the patriots, and the other in great sadness.

There are also three stone pieces on the trail which will remain as a legacy to Bruce once the wooden ones have gone.

One is The Sailor, featuring the haunting face of a sailor screaming from an unhewn stone block.

It’s an intensely personal work – a representation of Bruce’s brother’s terrifying last moments as he was trapped inside a sinking battleship during the Second World War, with no hope of escape.

Intensely personal work

Another stone sculpture simply bears the carving: “I was privileged to be.”

There’s also Millennium, in which a big hand holding the universe represents the force that started it all.

So, how do I feel about Bruce’s sculptures? I’d be lying if I said I liked them. I find them unsettling and deeply disturbing but they’re certainly impactful.

Deeply disturbing

They’ve made me think – about life, death, poverty, politics, Scottish culture and human relationships, which, I imagine, is what Bruce intended.

His art is exactly where it should be – deep in woodland in which it was “born”, and not in some stuffy indoor gallery.

It changes with the weather, becoming saturated and then drying out, and being altered by the wildlife that gnaws and nibbles at it.

Essentially, it is art that lives and dies.

Frank Bruce

Born in the fishing village of St Combs near Fraserburgh in 1931, Bruce left school at 13 to work in a sawmill.

Despite being dyslexic, he taught himself to read using comic books, and found expression through manual labour.

As his sculpting skills developed, he created his huge wooden pieces, some 20ft tall. They first filled his garden, and then Banff’s Colleonard Sculpture Garden. When Bruce moved to Aviemore in the 1960s, he moved his sculptures to Feshiebridge.

Return to spiritual home

Many had been carved from the ancient Caledonian pines of Inshriach Forest, so it was fitting to see them return to their spiritual home.

Throughout his career, Bruce, who died in Inverness in 2009, shied away from the commercial art world, never selling his works, instead, asking for donations to help him continue his craft.

He maintained that his art should be free for people to enjoy. As such, there’s no charge to visit the trail.

- The sculptures are cared for by Forestry Commission Scotland. For more information about the Frank Bruce Sculpture Trail see frank-bruce.org.uk/

Conversation