With its glorious sandy beach, extensive dune system and colony of seals, it’s no wonder Newburgh beach is so popular.

But when I set out for a stroll there a few days ago, I was in search of something rather unusual – ‘Hitler’s Graveyard’.

I’d long known of its existence, but a recent post on social media from Cruden Bay author and historian Mike Shepherd inspired me to finally hunt it down.

For readers wondering what on earth I’m going on about, I should point out that ‘Hitler’s Graveyard’ is in fact a unique carving on a concrete tank trap, dated 1940.

It’s very often buried in the sand, but knowing Mike had just seen it, I set off, armed with a sweeping brush and plastic scoop, as advised by the man himself.

It was a gorgeous, sunny summer’s day and I wasn’t in a rush.

Spotting seals

Seals galore were out to play, and I paused to watch as they splashed and frolicked in the sea and on the sands.

Hundreds of the creatures can be found at what’s known as the “Ythan haul-out”, the place they come ashore to rest, moult and breed.

At peak times, there can be more than 1,000 hanging out together in the vast colony.

They’re very vocal animals, singing, wailing, and emitting bizarre grunts, barks and honks.

A few grey seals were swimming round the partially-submerged wreck of Halcyon, a boat which came ashore during a storm in 1854 with the loss of eight lives.

Walking south, it didn’t take long to find what I was looking for.

The hunt for ‘Hitler’s Graveyard’

I knew ‘Hitler’s Graveyard’ was about half a mile down the beach from the seal observation area, in amongst a row of about 40 concrete defence blocks.

The artwork faces the sea, and to my delight, most of it was exposed. To fully uncover it, though, I needed to use my yellow plastic scoop!

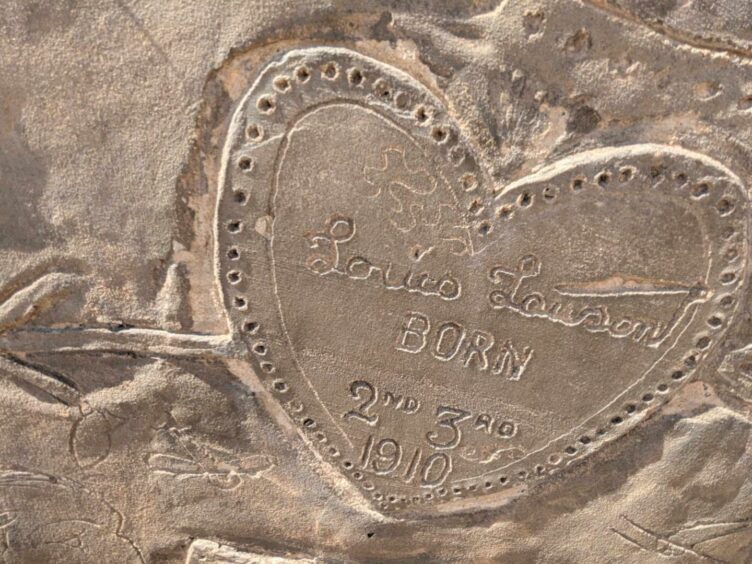

The decorated block, signed by Louis Lawson, and dated 1940, is pretty impressive.

It shows caricatures of Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler, who is gazing up at a falling bomb. And at the bottom is the chilling message: Hitler’s Graveyard.

So who was Louis Lawson? According to the carving, he was born in 1910, and it can be presumed he was one of the men putting in the line of defences.

Graffiti artist probably in Polish Army

Another local historian, Peterhead-based Mark Salt, reckons Lawson was probably in the Polish Army.

He told me: “The story I came across during research is that after the withdrawal from Dunkirk in 1940, the British went on a massive defence building spree around the UK using whatever troops we had, which included those of the allied captured nations.

“The story goes that a large group of Polish Army personnel were sent north to facilitate such a build of pillboxes (concrete bunkers) and tank stops on the beaches.

“During the build they left graffiti on some of the concrete builds while they were wet or uncured.

“In the case of Lawson, l couldn’t say for certain that he is Polish, but he may have been attached to a Polish unit at that time.”

And what, in Mark’s mind, does the phrase ‘Hitler’s Graveyard’ mean?

“That could have come about from any intended invasion area,” he said.

“Any troops landing on northern beaches would have been killed by defending troops thereby making a German graveyard.”

It’s pretty fascinating to think that after 84 years this carving sometimes surfaces, and yet remains hidden when wind blows sand over it.

I recommend heading along for a look soon while it’s relatively easy to find.

Beach defences

The reason for the tank traps on Newburgh beach?

When the Second World War broke out, the north-east of Scotland was considered an especially vulnerable site for a beach landing by the German army.

Beach defences, in particular, were deemed necessary to prevent tanks landing during the feared Nazi invasion.

The man responsible for the erection of beach defences in northern Scotland, from the Forth to Wick, was Chief Royal Engineer G A Mitchell, a veteran of the First World War.

In just a few months in 1940 he organised the construction of a vast array, including concrete blocks and complexes of interlocked tubular scaffolding poles which would hinder the landing of tanks and other vehicles.

He also designed barbed wire entanglements, pillboxes, mine fields and gun emplacements.

The tank blocks were usually cubes of concrete, cast on site, often with jagged rocks set on top, to further damage tanks. They were laid in a long line at high water mark.

Those building the blocks, as well as local children on occasion, sometimes scratched their names, messages, and simple graffiti in the still wet concrete of newly cast blocks.

The unusually richly decorated ‘Hitler’s Graveyard’ block is well worth checking out.

The effects of coastal erosion

The original positions of some anti-tank blocks have been altered heavily by coastal erosion over the years.

Some no longer stand upright, but lie on their sides, exposing the concrete rafts that they were placed on for stability.

On a few blocks, erosion has exposed iron latticework embedded in the concrete and pebbles and stones used in the concrete mix.

- Mike Shepherd’s new book, The Jacobites of North East Scotland, is out in September. See here.