Malcolm Macdonald’s father had been harbouring a dark secret for years. One he chose to share with his son when he was 10. The secret was that his father, also called Malcolm Macdonald, had drowned in the Iolaire tragedy, one of the darkest days in Britain’s naval wartime history.

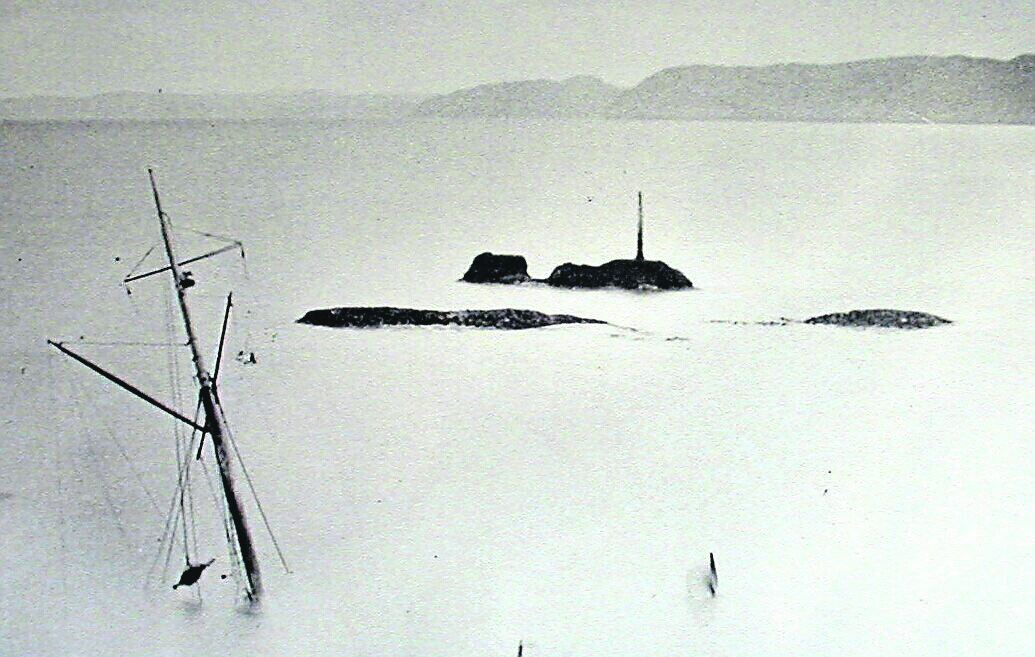

HMY Iolaire, a yacht packed with sailors who had managed to survive the horrors of the First World War, sank on the Beasts of Holm rocks, just yards from the entrance to Stornoway harbour in the early hours of January 1 1919 – with the loss of 201 lives.

The bitterly sad event caused ripples of pain, suffering and distress through the generations and altered the lives of hundreds of islanders, including those who survived.

Among them is Malcolm Macdonald, co-author of best-selling book The Darkest Dawn, which tells the story of the Iolaire tragedy.

“My father was a very easy going person, he never lost his temper and was always smiling, but he held a deep secret that my sister and I weren’t aware of until I was 10 and she was 17,” said Malcolm.

“That was his father, Malcolm Macdonald, who I’m named after, was lost on the Iolaire.

“We didn’t know anything about the tragedy until 1958 when it was suggested a memorial be erected on the island.

“We thought our grandfather had been lost in the war, not drowned within sight of Stornoway.”

What makes it all the sadder is that Malcolm had already cheated death twice.

He’d survived a sinking and the world’s worst maritime disaster and would undoubtedly have experienced feelings of relief that, as the lights of Stornoway harbour came into view, for him, the horror of war was finally over.

“My grandfather had survived the sinking of HMS Calgarian,” said Malcolm.

The merchant cruiser, built in Glasgow, was sunk by a U-boat in 1913.

Forty-nine people drowned, but Malcolm survived by clinging to a raft with another man from the islands, John Mackenzie, who, by a twist of fate, was also on the Iolaire that fateful night – but John survived.

“They had also been in Halifax, Nova Scotia, when the whole city was devastated by a huge explosion when an ammunition ship blew up. It was the biggest explosion the world had witnessed until Hiroshima.”

What they’d experienced in Halifax was horrific.

A French cargo ship laden with explosives was accidentally hit by a Norwegian vessel. Fire broke out and ignited the cargo causing a devastating explosion that killed around 2,000 people and injured 9,000.

To learn that relatives had survived those experiences only for them to perish within sight of their homeland caused such distress that, for decades, people simply didn’t talk about it, although the sinking had a knock-on effect that lasted for years.

“My grandmother had died of TB in 1911, so my father and his brother were made orphans by the tragedy,” said Malcolm.

“They were split up and brought up by uncles.

“The impact on children across the island was immense and many were orphaned, put into orphanages or split up and raised by relatives, and this was at a time when there was no social security system to help out,” explained Malcolm, who spent 20 years researching the book he co-wrote with Donald John MacLeod, who has since died.

The story of his grandfather is included in the book The Darkest Dawn, as is the story of each and every man on board – survivors and those who were lost – as well as details of the families and the communities they left behind.

There are many tales of bravery, but two which stand out for Malcolm are the stories of John Finlay MacLeod and Donald Morrison.

“John Finlay MacLeod was one of the last Iolaire survivors.

“He died in December 1978 when he was 90.

“I knew his family and he was a very, very shy and modest man.

“He was a carpenter and in 1917 had asked permission not to serve but he was forced to and ended up becoming a reluctant hero.

“He only spoke to his son twice about the events of that night, once in 1939 and again when the Iolaire monument was erected in 1960.”

His actions that night – for which he later received the Royal Humane Society’s silver medal for an act of gallant bravery, as well as other honours – saved the lives of 40 men, and in turn hundreds of people are alive today because of his bravery.

“John was from Port Ness, a small fishing port, and aged 30 at the time of the tragedy.”

His son, John Murdo, who sadly died a few weeks ago, shared the story of his father’s courageous actions in an interview in 1969.

He said: “A flare went up and he identified the area.

“Having decided on his course of action, he gave the end of a heaving line to a fellow beside him and told him that he must not let it go.

“My father didn’t put the rope round his middle, but two times round his left hand and locked the end of the rope with his thumb.

“Then he dropped into the water. At the first attempt, the surge carried him away from the shore.”

Malcolm said: “By his own account John said that he was far from the best swimmer on board but he’d studied the waves and could tell that every third wave would crash higher on to the rocks.

“The waves were dragging men back down into the water and because there’s a conglomerate-type surface on the rocks, a bit like harling, it was tearing the skin off their hands and knees.

“John managed to get a wave that crashed on to the grass, pulled himself up then got a hawser line set up and by all accounts managed to rescue about 40 people who clung on to the rope to reach safety.”

Donald Morrison’s story is also one of bravery.

“When the ship began to sink, Donald, known as ‘Am Patch’ Morrison, who was little more than a schoolboy when war broke out, climbed up the mast.

“When he saw John Finlay MacLeod going underneath the boat he said ‘Well, that’s the last we’ll see of him.’

“Thankfully, he was wrong.

“By the time he climbed the mast there was a force 10 gale blowing and the seas were wild.

“He survived by hanging on to the mast from five past three in the morning until he was rescued at 10 o’clock the next morning.

“At six in the morning the wireless aerial fell on his head and he heard a large crash – the other mast had broken off halfway up and the two men who were hanging on to it disappeared.

“He had a horrendous time, as his brother Angus, who was also on board, drowned.

“When he moved home he said he’d wished he’d stayed in hospital as he had to face his mother and imagined she was thinking ‘Why had he survived when his brother had drowned?’

“A lot of those who survived the tragedy had what was referred to as ‘survivor guilt’.”

Another terribly sad story relates to a chap called John Macaskill, from Lower Sandwick, outside Stornoway.

“There’s a cemetery there and his body was washed up on the beach outside the cemetery.

“On the far side of the same cemetery was his house.

“He must have been the only sailor who, after fighting for four years in the war, was washed up on his own doorstep.

“That’s terribly tragic.”

While the story of this tragedy wasn’t spoken about for years, as the 100th anniversary of the tragedy approaches, that’s all changed.

“People are suddenly aware of it and even locally the reaction has just been phenomenal,” said Malcolm.

He believes part of the fascination is due to the monumental sadness of the event – and the human experience of loss – as well as the enduring mystery of what caused her to hit the rocks.

“I think the stories were so sad that it plucked at the emotions and, as families, we’ve all gone through sorrow.

“Death doesn’t go away.”

The Darkest Dawn: The Story of the Iolaire Tragedy is available from www.acairbooks.com

The video shows a time lapse of the Iolaire installation In Stornoway Harbour – East