Our fascination with Egypt never grows old.

Last month alone saw two major TV shows – Egyptian Tomb Hunting with Tony Robinson, and Egypt Unwrapped – hit the small screens.

Meanwhile, a new exhibition entitled Discovering Ancient Egypt is bringing together objects and hidden stories from the collections of National Museums Scotland and Montrose Museum to reveal how ancient Egypt has captivated Scotland over the past 200 years.

Stories of tomb-raiders, ancient worlds and mysterious gods can still send a shiver running along the spine but not many people are aware it was an Aberdeen-born woman who helped shape our interest in Egyptian history and archeology, and that even today, experts rely on her work and drawings to help them put together pieces of the puzzle surrounding ancient Egypt.

Annie Abernethie Pirie Quibell was a fascinating, extraordinary woman, says Dr Daniel Potter from the National Museums Scotland (NMS).

Her name may not be too familiar but she’s considered to be so important that she was chosen by NMS to be a woman worth celebrating this year on International Women’s Day.

“Annie was born in 1862 into what was a modestly distinguished family in Aberdeen,” said Dan.

“Her dad was connected to the university and her brother would later become a professor of mathematics, so they were quite an educated family.”

The family home was at 13 Bon Accord Square and it was there that a young Annie would have been encouraged to learn more about the world and study art, a subject she was particularly good at.

“She trained as an artist at Glasgow College and some of her work was exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy,” said Dan.

“In the 1890s she attended university in London and gained a degree in Egyptology. That was pretty unusual as, at the time, University College London was the only university in the country that allowed women to take a degree course.”

Annie set off for Egypt – at that time it wasn’t unusual to find women such as Annie working on archeological sites and digs.

At university she’d met famous archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie. He and his wife, Hilda, were responsible for excavating several key archaeological sites across Egypt and made many significant discoveries, including the Qurna burial.

In 1895 he asked Annie to join them and she went on to excavate at several key sites, including one of the earliest temples in Egypt, at Hierakonpolis.

“While the work women like Annie were doing was vitally important, they were often regarded as an invisible pair of hands,” said Dan. “Any significant discoveries made would be credited to the person in charge of the dig, while those working alongside would be lucky to get anything more than a mention in notes.”

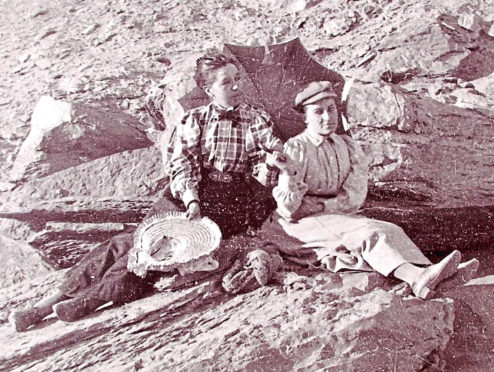

During one excavation Annie met renowned Egyptologist, James Quibell. They met in a most unromantic way, as both were suffering from a bout of food poisoning. They married in 1900 and worked together in Egypt until 1914, including spending eight years at the site of Saqqara.

“When she married Edward, they became a bit of a dream Egyptology team and were always spoken about as a couple, which really reflects how much work they both shared,” said Dan.

“She was responsible for a huge amount of work. For example, we have letters in the archives where Edward starts writing but can’t finish off the paperwork so Annie completes it.

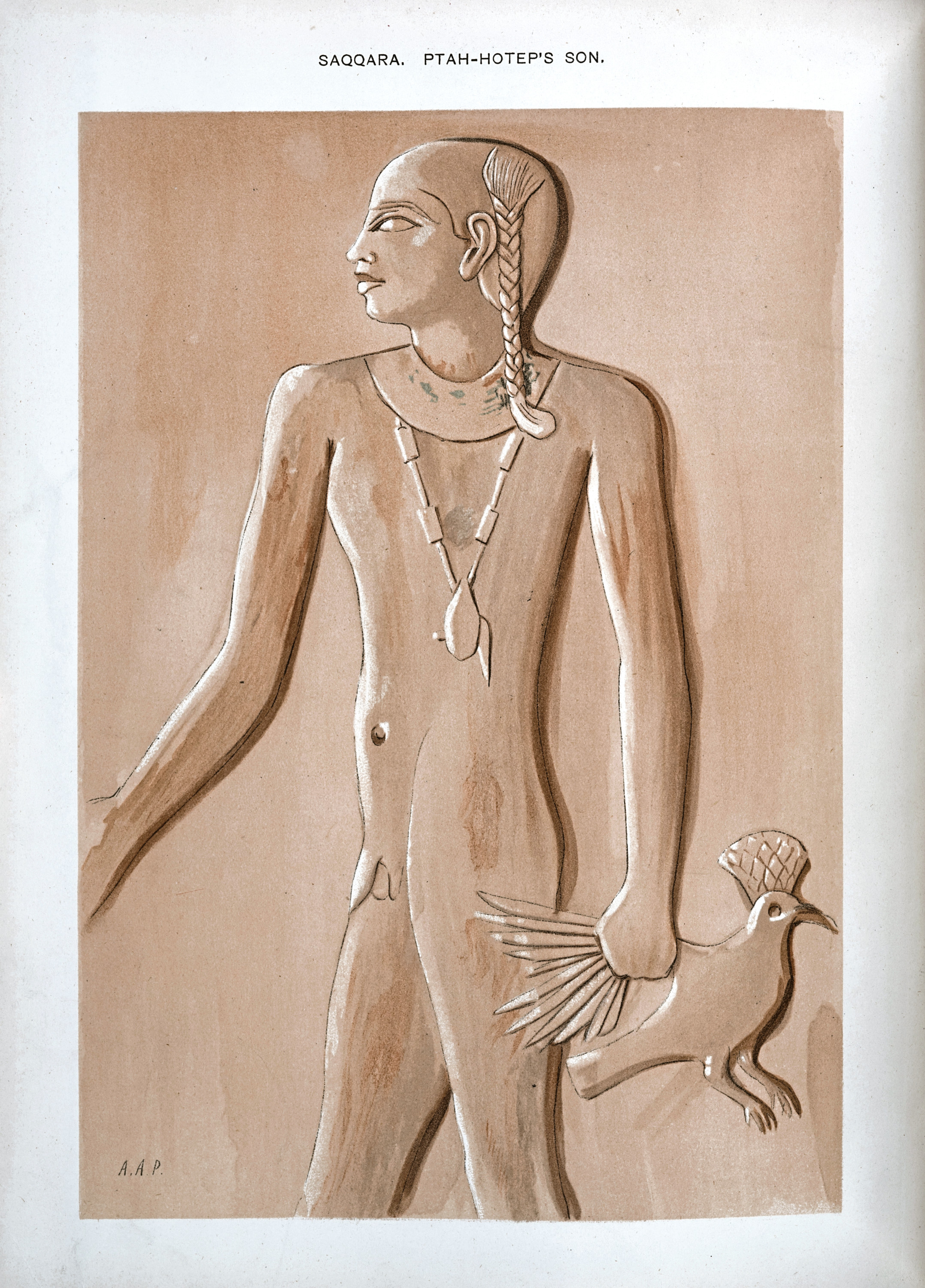

“The work she was doing, particularly the intricate, detailed drawings she did, were really vital to research. Photography wasn’t a big thing then so the drawings she made are completely vital and still used today.

“As with all aspects of archeology, things get lost or broken but Annie’s drawings are full of detail, but also include details of exactly where things were found.

“Her drawings have become a very useful tool for us.”

Swapping the cool weather found in the North of Scotland for the heat of Egypt, doesn’t seemed to have affected Annie. Nor did swapping a comfortable home life for basic facilities.

“Sometimes they would live in a tent at the dig site but at other times they lived in a tomb,” explained Dan. “Annie is famous for saying: ‘Of all the different dwelling places, give me, for choice, if not too long a time, a good tomb.’

“She took to life in Egypt like a duck to water, although it was totally different to the life she’d had in Aberdeen.

“Clearly she relished the time she spent in Egypt with her husband and illustrated hundreds and hundreds of unique finds and objects, and helped excavate numerous items.

“She also wrote guide books which are wonderful to read, as she has a lovely turn of phrase.”

Annie produced many of the object illustrations for the excavation publications of the Egypt Exploration Society, which was founded in 1882 by the writer and Egyptologist Amelia Edwards, and which funded many of Petrie’s expeditions.

Her illustrations include objects found at Hierakonpolis which are now in the National Museums Scotland collection and she was responsible for arranging the Egyptian gallery at the Marischal Museum at Aberdeen University.

One of the biggest events they were involved with was the St Louis World Fair where they created life-size recreations of ancient Egyptian life which generated a huge amount of interest.

In 1927, at the age of 65, Annie died of leukaemia, and is buried in Old Machar Churchyard in Old Aberdeen.

Through her intricate drawings and books, she left a lasting legacy, which is still used by researchers today.

“Those who knew of her work thought very highly of her,” said Dan.

“There was much going on at the time in terms of discovering more about Egypt and Annie definitely had a part to play in that.

“She was well read and well received. When she died, she received a glowing obituary.”

It would be good if this Aberdeen-born heroine was more widely recognised but at least we can explore the legacy she left behind.

Objects excavated and illustrated by Annie can be seen in the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery on Level 5 at the National Museum of Scotland and in the touring exhibition Discovering Ancient Egypt.

The exhibition looks at Scotland’s contribution to Egyptology through the lives of three people, including Annie, whose work helped to improve our understanding of ancient Egyptian culture. The others include Wick-born Alexander Henry Rhind (1833-1863), the first archaeologist to work in Egypt, and a pioneer of systematic excavation and recording. On display will be objects from a tomb he excavated including a Book of the Dead papyrus belonging to a Prime Minister and inscribed wooden labels which were discovered with the mummified remains of 10 princesses who shared the same royal tomb.

Also featured is Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900) who served as Astronomer Royal for Scotland and carried out the first largely accurate survey of the Great Pyramid and the first-ever photography of its interior with his wife, Jessie.

Earlier this year, three new galleries opened at the NMS of Scotland including one dedicated to Ancient Egypt.

Discovering Ancient Egypt will be on display at Montrose Museum from June 8 to September 7. Contact

nms.ac.uk/egypttour

for more details.