With your life in their hands, it’s little wonder some patients see surgeons as living gods.

But no amount of skill with a scalpel can change the fact surgeons are real people too, with emotions and frailties that usually remain hidden behind those sterile surgical masks.

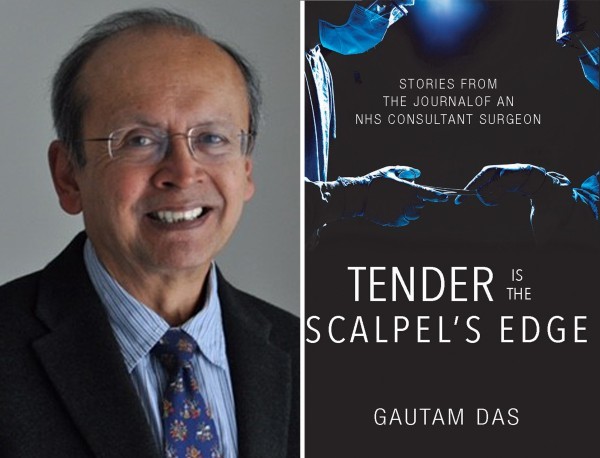

After serving more than 40 years in his profession, retired surgeon Gautam Das lifts the lid on the thoughts and feelings behind the professional surgical demeanour, in his new book Tender Is The Scalpel’s Edge.

And here are the eight things you need to know about being an NHS surgeon:

1. A calm demeanour is an essential skill

Das, 67, believes part of a surgeon’s skill is remaining calm, no matter what unexpected turns an operation takes.

“Before an operation – and in my book there’s no such thing as a small operation, every one is big to me – as soon as I gowned up and put on the rubber gloves and heard them snap on, a calm used to descend,” he explains.

That calm professionalism has enabled Das to perform operations as complex as kidney transplants and radical cystectomies (removal of a cancerous bladder together with the prostate/uterus, regional lymph nodes and the urethra).

2. The job requires precision focus and absolute concentration

When you know mistakes can cost lives, staying alert and on focus is important.

Das writes in his book: “Absolute focus and concentration is required as one is working with sharp instruments at very close proximity to large blood vessels which are unforgiving if disrespected.”

3. But job satisfaction is pretty high when you know you can save lives

One of the things Das loved most about his job was the satisfaction of knowing he’d performed an operation “meticulously”.

“At the end of the day, surgery is art,” he says. “Of course you need your knowledge base, but if you do the operation well, you feel great.

“Saving a life may sound cliched, but when it’s there and it’s real, it’s a wonderful feeling.”

4. Confidence comes with the job description

Surgeons have to carry themselves with a certain level of confidence – after all self-doubt doesn’t inspire trust among patients.

But sometimes people can forget that surgeons too are humans.

“As a consultant surgeon in the NHS, you have a huge responsibility – you’re like an army commander, and the most important thing is that you command confidence,” he says.

“But behind that there’s a human being with all the things that come with that, and some of it is self-doubt. That’s what I wanted to get across – it’s not a text book of surgery, it’s not about me, it’s about the emotions, the love, the tenderness.”

5. Your job can emotionally affect you

Das admits in the early years of training, he questioned whether he could cope with the harsh realities of his profession.

“Seeing disease in a text book is one thing, but when you come to the ward and see a little boy crying and missing his mother and yet we’re learning about his childhood cancer, it’s hard.

“I nearly gave up medicine because I thought I couldn’t be doing with that side of it.”

6. You go through heartbreaking experiences

Despite the impressive letters after his name, Das is a sensitive man who is at pains to stress that doctors should never become hardened to the suffering and death sometimes associated with their work.

“If you don’t feel anything when a patient dies, it’s time you stopped and did something else,” he insists.

Das’s career saw him practise as a surgeon for 26 years, during which time he only lost one patient – a 64-year-old man undergoing a radical nephrectomy (the removal of a cancerous kidney) – on the operating table, and it’s imprinted on his mind as one of the worst things he ever experienced in the job he otherwise loved.

In the book, Das writes: “We are not encouraged to fold up. Yet, if one is entirely honest, some recollections, and their effect, are impossible to entirely erase. Some things are inescapable, even for surgeons.”

7. Patients need care and support

Doctors have to find a tough balance between seeing as many patients as possible and sometimes being the messenger delivering heart-breaking news.

Das says when a doctor has to see many patients within a certain time-frame, but one has to be told he has cancer, “you just can’t say, ‘You’ve got cancer, here’s a leaflet, go away and read about it and we’ll talk about it in two weeks’.

“You just can’t. You have to take time, and your clinic goes on and there are people outside waiting. That sort of thing can grind you down.”

8. Working for the NHS is a privilege

Despite the current furore about lack of funding and efficiency in the NHS, Das insists the UK’s health service is fantastic.

“Our NHS is amazing – people in the rest of the world don’t realise what a great thing the NHS is. It’s incumbent on all of us who have the great honour and responsibility of practising in the UK to bear that in mind.

“People talk about an adversarial relationship between clinicians and managers, but I don’t think that’s fair because the poor managers are doing a very difficult task.

“I would hate to be the chief executive of some of these front-line hospitals, with all the pressures of juggling the finances with the service you have to provide.”