It was one of the most important military encounters of World War II.

And even today, on the 75th anniversary of the Battle of El Alamein, when the dwindling number of survivors’ eyes are old and grey and full of sleep, the significance of what happened in the desert between October 23 and November 4, 1942, cannot be overstated.

As Winston Churchill declared, in the aftermath of the hostilities: “Before Alamein, we never had a victory; after Alamein, we never had a defeat.”

And Scots were pivotal to the success of the action, which raged around the Egyptian town 60 miles west of Alexandria.

Nine battalions – the 1st, 5th and 7th Black Watch, the 1st and 5/7th Gordons, the 2nd and 5th Seaforths, and the 5th Camerons and 7th Argylls – formed the Highland Division’s three brigades: 152, 153 and 154.

And many of these troops, who had endured myriad privations and escaped by the skin of their teeth at Dunkirk and elsewhere, were finally able to settle a score with Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the German commander of the Afrika Corps, who had proved himself a tactically astute and charismatic figure.

At the forefront of the conflict, the British fought shoulder-to-shoulder with Australians, South Africans, New Zealanders, and men from 11 other countries involved in the struggle.

Yet it was a measure of the impact which the Caledonian contingent had on the rest of their Allied colleagues that the 51st Highland Division, which had sailed from the Clyde to Egypt four months earlier, was so effective.

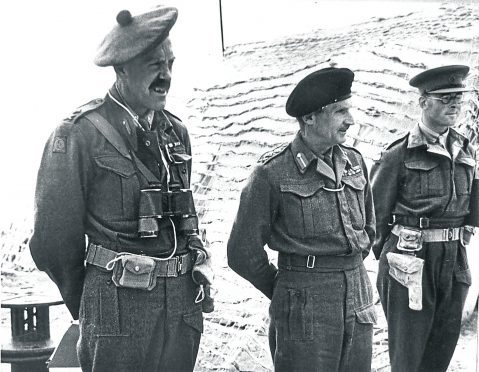

The commander of the 51st was Major-General Douglas Wimberley, a Cameron Highlander – and Inverness man – who had fought on the Western Front in World War I.

And, although he died in 1983, one of his final interviews was with the Evening Express journalist, James Lees, now 94 and still living in Aberdeen. As Mr Lees recounted: “General Wimberley lost no time getting his men trained for the battle. In an area of open desert, an exact replica was made of the part of the Germans’ defences which the division were to attack.

“Names of Scottish towns and villages, including Aberdeen, Inverness, Stirling, Nairn, Ballater, Kintore, Cruden and Killin, appropriate for the regimental area, were given to enemy positions they had to capture.

“The men knew an attack was coming, but none of them knew the place or the time. Then, on October 6, all senior officers went to a full dress conference, held by Lt General Sir Bernard Montgomery, where the Eighth Army commander revealed that 30 Corps was to carry out the big assault later that month.

“The 51st was the only one from the United Kingdom. The plan was for the 10 Armoured Corps to pass through when the 51st had captured their objectives.”

Nobody expected it to be easy. Rommel and his compatriots were tenacious, resolute antagonists, who knew their terrain and weren’t prepared to relinquish their grip on it.

And yet, as one visit to the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen makes very clear, the courage and sacrifice of those who participated in the battle from across the north and north-east of Scotland was all-encompassing.

Ruth Duncan, the curator of the museum on Viewfield Road, has understandable awe for those indomitable warriors who joined the fight against the Afrika Corps.

She said: “A lot of them were young people and it must have been their first experience of such conditions, but the bravery they displayed from the start of Operation Lightfoot was remarkable.

“It was an extremely well-organised campaign, and Montgomery was meticulous – he had worked on the strategy for months before it started – but there was still a massive human cost.

“The casualties added up to 13,500 soldiers, who were killed, wounded or missing in action. There were over 7,000 deaths recorded of Commonwealth personnel at the Alamein memorial. There are also more than 9,000 names of soldiers with no known grave. The hostilities continued until November 4 and, although it turned out to be a success for the Allies, there were so many individual stories which testified to the sacrifices of those involved.

“One young man, Private Walter Drake Hendry, was only 20, and he was killed on the first night of the battle. He had sent a Christmas card to his family, but it didn’t arrive until weeks after his death.

“There was a lot of preparation before the hostilities began, but you can only do so much. And so many officers were mortally wounded at Alamein that all the subalterns were promoted to temporary captains.

“In the end, though, it definitely proved to be a turning point. Churchill said later it wasn’t the beginning of the end, but it was the end of the beginning. It helped turn the tide in the Allies’ favour.”

All the same, Maj Gen Wimberley recognised the scale of the losses. He later wrote: “As I motored forward, I saw, every 100 yards or so, wounded men, mostly sappers who had become casualties on the mines.

“At intervals all down the road, mile after mile after mile, the enemy had spread shovel-loads of sands and, under every sixth heap or so, a mine had been buried. The roads, with the corpses of our poor dead, who we lost out on patrol, were all booby-trapped, when the burial parties went out later to clear the battlefield and bury them.

“Never again, while I commanded the Highland Division, did we ever meet such a heavily-mined area.”

Those who survived were treated as heroes. But it was not until the night of November 1, when Montgomery launched the second phase of his attack, Operation Supercharge, that the momentum inexorably shifted in his favour.

By the following day, Rommel warned Hitler that his army faced annihilation, but the Fuhrer ordered the “Desert Fox” to “stand and die”.

It was to no avail as the Allies streamed forward, and the Germans were forced to retreat.

At midday on November 4, Rommel’s last defences caved in and, eventually, he received orders from Hitler to withdraw and eventually move out of Egypt into Tunisia.

It was a critical victory and, back in Britain, the church bells were rung for the first time since May 1940, to celebrate the Eighth Army’s triumph.

The outcome was momentous, not only in the North African campaign, but also the greater conflict.

It ended the long fight which had raged in the Western Desert and was the only major land battle won by the British and Commonwealth forces without direct American participation.

And, as Mr Lees stated, while Montgomery gained most of the accolades, Maj Gen Wimberley’s role was crucial to the undertaking’s success.

He recalled: “As we left his study, he pointed to a pennon on the wall. It was the one he flew on the Jeep which had been destroyed by a mortar or mine at the start of the battle.

“It was later discovered intact and he used it during the rest of the North African campaign.

“It was a reminder of the long and arduous conflict fought by the men he commanded. And, in his words, ‘the Jocks lived up to the words: Scotland forever and second to none’.”

‘In the traditions of their past’

By Ruth Duncan, curator, Gordon Highlanders Museum

In June 1942, a newly formed 51st (Highland) Division set sail for Egypt. Now part of the renowned Eighth Army, they were keen to avenge the capture of the original 51st at St Valéry-en-Caux in June 1940 by none other than the opponent they now challenged – Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the ‘Desert Fox’.

1st and 5th/7th Battalion The Gordon Highlanders played their part in the advance of October 23 and also in the ensuing days of fighting which followed. Major-General Douglas Wimberley, commanding the Highland Division, wrote later that the Gordon battalions had “fought in the best traditions of their great past” during this important battle.

Lieutenant Ewan F Frazer of 1st Gordons was just one of the many men who played a unique and unforgettable role in this famous campaign. Frazer was commanding a platoon of ‘A’ Company on the night of October 23 when it came under heavy fire from a German machine-gun position. Taking a section of eight men, he attacked and destroyed the enemy position. By the time he returned to his own position, two senior officers had been wounded. Taking charge of ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies, Frazer led them forward to secure their objectives.

A short while later, the battalion soon came under further machine-gun fire. Frazer went forward, this time alone, armed with a rifle and bayonet and a stock of grenades. He attacked four German dug-outs, destroying all of them in turn. At dawn, he again attacked an enemy position alone, taking seven Germans prisoner. For his leadership and courage that night, he was awarded an ‘immediate’ Distinguished Service Order.

El Alamein ended with the German and Italian forces in full retreat, but was won at a considerable cost to the to Allies, as nearly a quarter of the Eighth Army’s number was killed, wounded or missing.

Mines mission

A company of Gordon Highlanders who were detailed to break through a minefield at El Alamein and attack enemy machine guns rode into the thick of the action on the afternoon of November 3, clinging five apiece to the tops of tanks.

One of those involved in the foray, Sergeant George McHolland, from Aberdeen, subsequently described the incident as being akin to something from the Battle of Waterloo.

He said: “We felt like knights of old, going into battle on our armoured chariots.

“What struck me was that we were reliving the days of Waterloo when the Gordons held on to the stirrups of the Scots Greys and got into the thick of the battle.”

Sgt McHolland continued: “I sat on the side of one tank with a Bren gun at the ready. We came to the minefield and followed behind the tanks.

“But we could not get through until the armoured divisions came forward next morning after a good deal of hard fighting.”

During the incursion, 14 men were killed and 46 wounded, while four officers perished and another four were wounded.

Six tanks were burnt out and 11 were severely damaged.

But the mission ultimately achieved its objective.