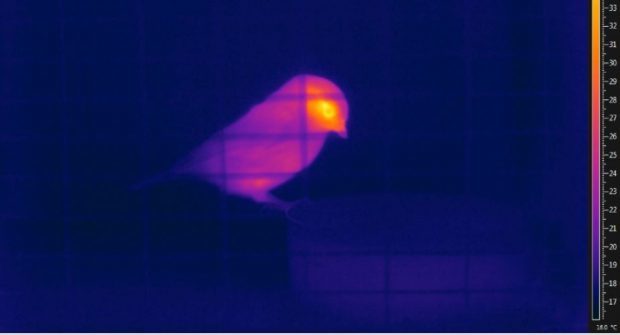

A new study using thermal imaging cameras is helping scientists monitor the wellbeing of wild animals without the need for them to be trapped and handled.

The work could transform how biologists investigate the responses of wild animals to environmental change and has been carried out by Glasgow University at the Scottish Centre for Ecology and the Natural Environment (SCENE) at Loch Lomond on a native population of blue tits.

The skin temperatures around the bird eyes were found to be lower when the creatures were in poor health and also those which have high stress hormones in their bloodstream.

Animals experience high levels of stress if food is scarce during spells of bad weather and it is possible that they could be trying to conserve energy by reducing their body temperatures.

The thermal imaging technique means biologists can now learn how animals are responding to their surroundings without having to capture them for examinations.

Paul Jerem, from Glasgow University’s Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine faculty (IBAHCM), said: “These findings are important because understanding physiological processes is key to answering the questions of why animals behave the way they do, and how they interact with each other and their environment.

“Changes in the physiological processes we detected using thermal imaging are generally the first response to environmental challenges. So being able to easily measure them means we might be able to identify populations at risk before any decline takes place – a primary goal of conservation.”

Dominic McCafferty, senior lecturer at IBAHCM, added: “Current methods of investigating physiological state in free-living species still generally mean animals need to be trapped and handled, something which is difficult, potentially invasive, and limits research to those species which can be easily caught. Additionally, natural patterns of behaviour are also interrupted.”

For more information please visit: https://t.co/mPkglKU2mX