Life was grim for the legions of young soldiers who sustained injuries during the Great War.

Many in the trenches succumbed to sepsis, and the mud and grime which pervaded the conflict often meant that troops perished from apparently innocuous wounds.

However, one pioneering surgeon from Aberdeen did his utmost to transform the situation and ended up making a huge difference to the lives of thousands of casualties.

>> Keep up to date with the latest news with The P&J newsletter

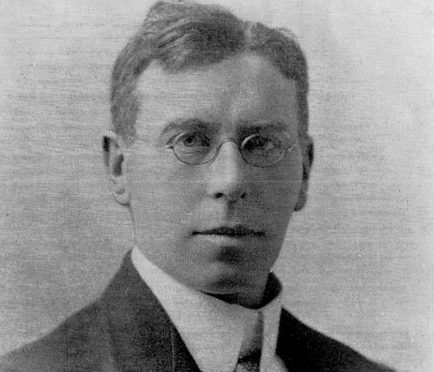

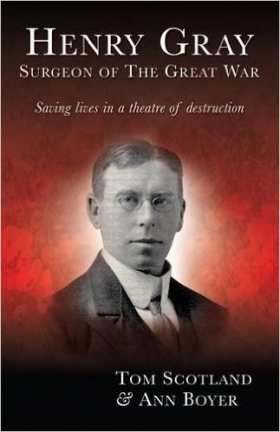

His name was Henry Gray, and now biographer Tom Scotland – another medical man from the Granite City – wants to make him better known in his homeland.

It has become almost a crusade for the retired orthopaedic surgeon, who has spent much of the last decade researching and writing a book in association with Ann Boyer, the great-niece of the distinguished north east surgeon, who died in 1938.

And he told the Press and Journal why it would be fitting if the centenary of the end of the war allowed a new generation of Scots to commemorate the achievements of one of the great unsung heroes of the conflict 100 years ago.

Mr Scotland said: “In 1914, surgical methods were hopelessly inadequate. Soldiers with filthy contaminated wounds had antiseptic dressings applied before being sent by hospital train to base hospitals on or near the French coast for definitive surgery.

“The journey took far too long and thousands of men succumbed to overwhelming septic wound infections and to gas gangrene.

“Gray pioneered wound excision, which is the early radical removal of all dead tissue and contaminated tissue from wounds; the removal of clothing, metallic fragments and excrement; and the conversion of a filthy contaminated wound to a clean one.

“Urgent limb and life-saving surgery was performed at Casualty Clearing Stations, much closer to the front. Effective surgery was delivered much sooner, significantly reducing the incidence of lethal wound infections and thousands of lives were saved.

“One of the worst wounds was the compound fracture of the femur (thigh bone) caused by gunshot or shell fragment. The percentage mortality in 1914 and 1915 was 80% because hopeless splintage of fractures resulted in excessive bleeding.

“Patients arrived at clearing stations in shock due to blood loss and they were unable to withstand wound excision to save their limbs and lives.

“In 1917, Gray ensured that all cases of compound gunshot fractures of the femur were immobilised much more effectively in a Thomas Splint.

“Most patients arrived in good clinical condition and were fit enough to undergo wound excision. Mortality was reduced to less than 20%.”

Mr Gray also opened a centre in 1917 to promote research into clinical shock, which was a major killer at the time. He was also an early advocate of blood transfusions.

Mr Scotland has closely studied his subject and has no doubt that Mr Gray was happier working in the field and adopting a hands-on approach to his vocation than following the example of some of his contemporaries, staying detached from the horrors of war.

He said: “Gray had strong principles and always put his patients first.

“He expected his team to do likewise. He was extremely supportive of young surgeons working in casualty clearing stations and was much admired by them.

“He was always in the thick of things when there were many casualties from a battle.

“But he got on less well with his contemporaries and he could be prickly. Some accused him of being too arbitrary and dictatorial.”

Nonetheless, his labours led to him receiving a knighthood and he continued to devise new means of tending to the sick and wounded throughout his life.

His biographer said: “Gray made enormous contributions to war surgery during three and a half years spent in France.

“He was mentioned in dispatches five times, he gained a knighthood for services to war surgery, and he was subsequently awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Letters by Aberdeen University.

“Yet hardly anyone knows his name in his home city. I wanted to make people aware of this great surgeon.”

Henry’s early life

Henry McIlltree Williamson Gray was born in Aberdeen on March 14, 1870 and was the fifth child of Alexander Reith Gray and Barbara Shand Anderson.

He attended Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh and studied medicine at Aberdeen University, graduating with honours in 1895.

After serving as house surgeon to Sir Alexander Ogston, Professor of Surgery at the university, he studied in Germany for eighteen months where he learned the techniques of aseptic surgery.

He introduced this in Aberdeen when he became a consultant surgeon in the city in 1904.

In the years leading up to the war, he established himself as a surgeon of outstanding ability who set himself very high standards and expected others in his team to follow suit.

In addition to being credited with bringing aseptic surgery to Aberdeen, he was instrumental in introducing local anaesthesia to surgery in Britain.

The letter

There are few artefacts left behind of the work which was carried out by Henry Gray in the trenches during the Great War.

But one item which has survived is a letter which was written by Gray to his sister Eva.

The correspondence was penned from base hospital in Rouen in 1916 and it happened in the most poignant of circumstances.

Gray`s brother John had just been killed in Mesopotamia and the surgeon was commisserating with Eva and at the same time as telling her about the litany of awful things he had to deal with.

He said: “Damn this war. It gets on my nerves so much, going round as I do and seeing the worst cases.”