It was the global conflict that led to a lost generation and, in the words of Wilfred Owen, created an anthem for doomed youth.

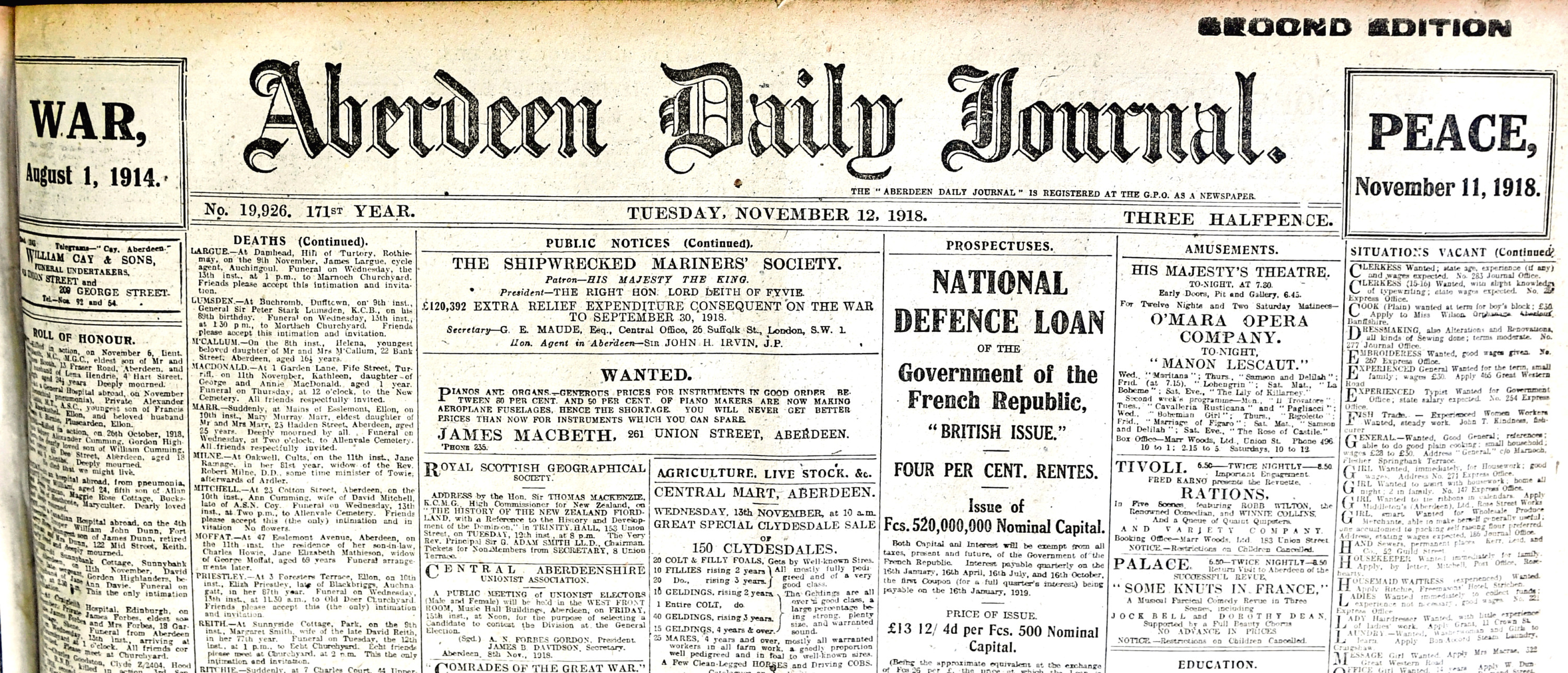

And although the First World War finally ceased 100 years ago this weekend, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, its impact still resonates in every community across Europe and further afield.

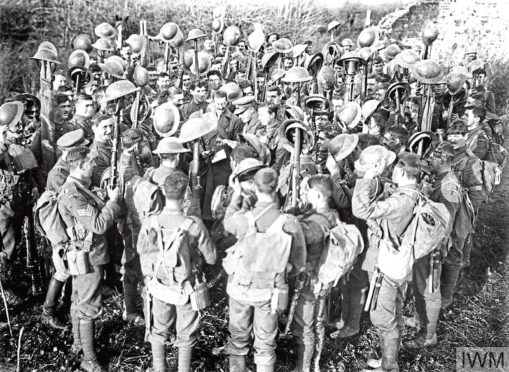

Triumphant scenes greeted Armistice Day in 1918 and huge crowds rejoiced in Britain’s major cities.

From the throng that assembled outside Buckingham Palace to the cheering masses in Aberdeen, Inverness, Edinburgh, Glasgow.

The British people had endured loved ones perishing and pals’ battalions fading into the ether in the trenches, or at sea, in the air, or in previously unknown battlefields.

The Press and Journal reported the ecstatic scenes that greeted the Allied victory, but it did so in terms reflecting both patriotic pride and exhausted relief.

Prime Minister David Lloyd George declared: “The Great War has been like a giant shell-star, flashing all over the land, illuminating the country and showing up the deep, dark places.

“We have seen places that we have never noticed before and we mean to put these things right.”

That, of course, offered scant consolation to the injured and families of the fallen, who suffered on an almost unimaginable scale.

The casualties on the Western Front from 1914-18 amounted to more than two million Allied fatalities and nearly 1.5 million German and Austrian losses.

Those officially wounded numbered at 5,157,000 among the Allies and 2,589,000 on the opposing side.

But there were many millions of others who were left haunted by the scenes of horror they had witnessed in the worst of the protracted hostilities.

Nobody was immune. Stories abounded of terrible sacrifice such as that endured by the Tocher family in Aberdeen.

When war broke out, Peter and Elspeth Tocher had five sons, Peter, George, James, John and Robert, all of whom served in the Gordon Highlanders regiment.

And all five of them died.

George Tocher was the first to perish after being injured while fighting near Ypres in May 1915. He later succumbed to his wounds and was buried in a military cemetery in Belgium.

The Battle of the Somme then claimed the lives of three more of the north-east men.

James and John Tocher died in July 1916, but their bodies were never found. Robert Tocher died in November, and was buried in France.

Peter Tocher was captured by the enemy in 1914, and spent the rest of the war in a German prisoner of war camp.

Their father, Peter, was so distraught at these unfolding tragedies that he enlisted in early 1916, but was deemed to be too old for military service.

There was even a bitter counterpoint to the story when eldest son Peter, who had survived the war, contracted tuberculosis during his time in the prison camp and never fully recovered, breathing his last in October 1923.

However, because his death came after the war, he was not entitled to a Commonwealth War Grave and was buried in a pauper’s grave in Trinity Cemetery in Aberdeen.

Such stories explain why Scotland both celebrated on Armistice Day and resolved that such a conflict should never happen again.

For a time, it was decreed this would be the “war to end all wars”. But only for a time.

Longer lasting was the social change and scale of technological advances which happened both during and after the war.

At the outset, soldiers still campaigned as if they were fighting in the Victorian era.

But, in the space of a few years, there was the development of tanks, submarines, fighter planes and chemical weapons.

So, too, those who stayed at home saw action and suffered casualties unlike in previous campaigns. And, whether in crowded cities or on remote islands, death was a constant intruder.

More than 800 men died when a series of internal explosions destroyed HMS Vanguard in Orkney on the night of July 9 1917.

The dreadnought battleship, which was involved in the Battle of Jutland, had been anchored in Scapa Flow when it was devastated by on-board explosions.

Just three of the 845 men who had been on the vessel were recovered alive, and one later died of his injuries.

The wreck now lies in 14m of water, to the north of the island of Flotta and has statutory protection as a designated war grave.

During past conflicts, the civilian population could only read about what was happening through heavily-censored newspaper reports. But this time there was no disguising the scale of losses on both sides.

And with vast numbers of men being conscripted as the casualties mounted, women became increasingly important to the war effort; a development that was as significant to them eventually gaining the vote as the Suffragette movement.

Some even journeyed to Europe to become nurses and old class and gender barriers were broken down on an unprecedented scale.

There were the redoubtable females who formed the Scottish Women’s Hospital unit and travelled to Salonika in the summer of 1916, then remained on the Balkan Front until the following year.

They included characters in the mould of Isobel Ross, who was born on Skye in 1890 and joined the hospital ship Dunluce Castle, on her way to a nursing station in Greece.

Her diary – published by Aberdeen University Press after her death – gives a vivid impression of their invaluable contribution.

By the middle of 1918, weary troops had almost reached the stage of being punch-drunk.

In a final throw of the dice, the Germans launched five major offensives – Operations Michael, Georgette, Blucher-Yorck, Gneisenau and Friedensturm – but they ultimately failed to produce a major breakthrough.

And, with the Allied forces being bolstered by 200,000 American soldiers per month, the tide eventually, decisively turned in their favour.

Following the success of the Battle of Amiens – where the British Fourth Army captured 80 square miles, 27,000 POWs and 450 guns in a single day on August 8 – they launched a series of co-ordinated offensives in late September.

And their mission to pierce the Hindenburg Line succeeded in the first week of October, as the prelude to the Germans asking US president Woodrow Wilson to broker an Armistice agreement.

This finally came into effect on November 11, and there were raucous celebrations, including an orchestral concert at the Tivoli Theatre in Aberdeen and other celebratory events across the north and north-east of Scotland.

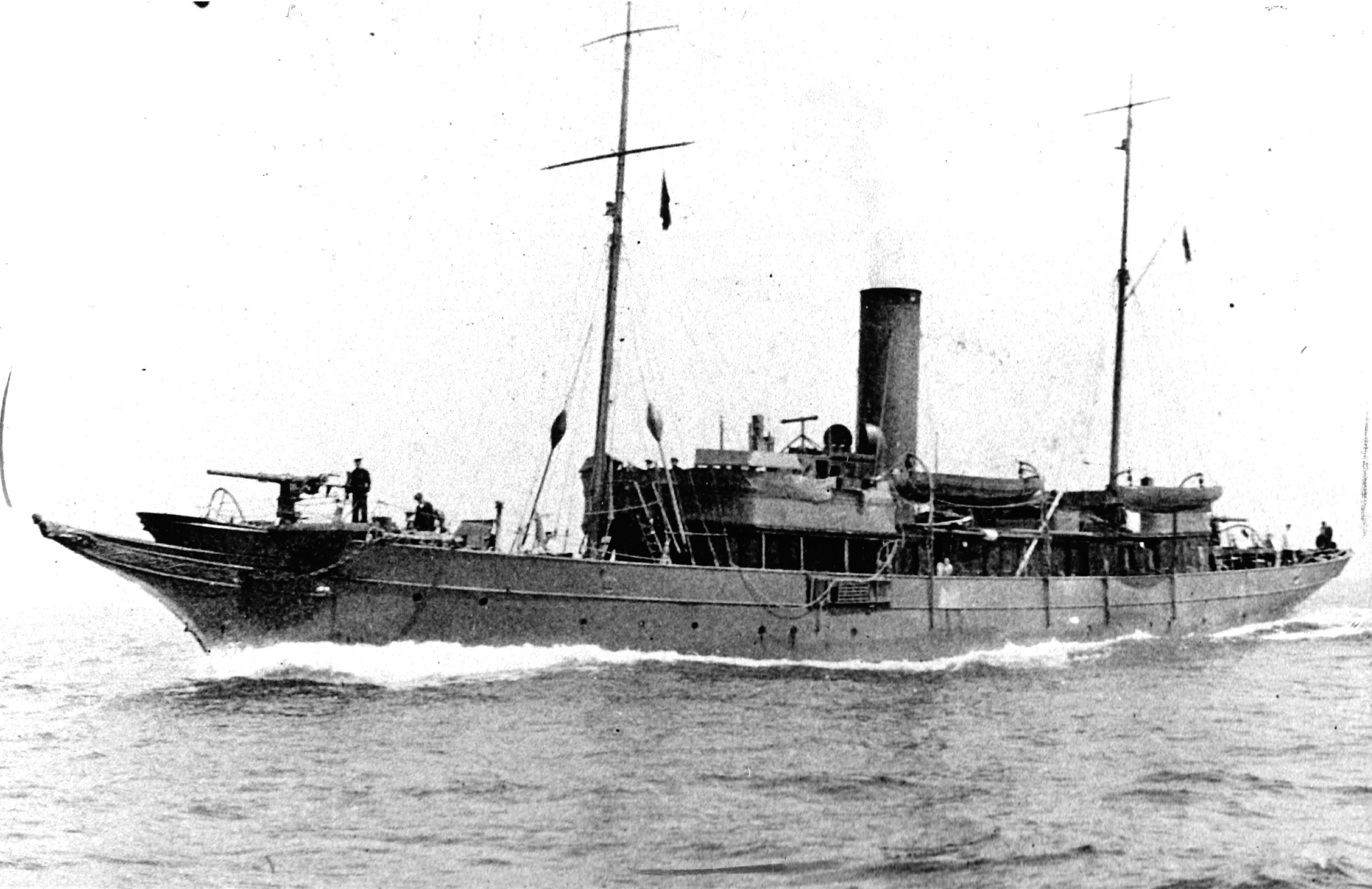

But any triumphalism was tempered by how many men remained in Europe, either incarcerated in prison camps – such as the Aberdeen crew of the fishing vessel Rubislaw which had been captured at the very outset of hostilities – or mired in red tape.

Many did not return to their loved ones until 1919.

Others, including the crew of the Iolaire, suffered the cruellest fate of all when they survived the war only to perish within touching distance of peace.

No fewer than 205 people died in the disaster on New Year’s Day: 174 Lewis men and seven Harris men, sailors who had survived the slaughter, were only yards from the shore, and whose families watched to welcome them home.

Lloyd George famously said he wanted “To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in.” And there was a radical construction programme and determination to transform urban society after the war.

A Ministry of Health was created. The 1918 Education Act raised the school leaving age to 14 and introduced state nursery schools.

Within a decade, there were women in the House of Lords and Commons.

But what of rural society? What of the countless farming and fishing villages whose men were scythed down or tormented by U-boats?

Lewis Grassic Gibbon, the author of Sunset Song, mourned the loss and deprivation of these Mearns towns and Highland villages and said they would never be the same again.

Then he wrote: “You hated the land and the coarse speak of the folk and learning was brave and fine one day; and the next you’d waken with the peewits crying across the hills, deep and deep, crying in the heart of you and the smell of the earth in your face, almost you’d cry for that, the beauty of it and the sweetness of the Scottish land and skies.”

Those who returned to these surroundings found some solace in being released from the trauma of the trenches.

But very few spoke of it.

Some were changed personalities, in the days before post-traumatic stress disorder was known or acknowledged.

What was irrefutable to those who curate at such places as the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen was that Britain was never the same place again after 1918.

In these pages, we pay tribute to those whose sacrifice ensured victory.