Once the guns and the shelling had been silenced and the war was over, one might have imagined that most of the combatants would have returned home in a matter of weeks.

But the truth was appreciably different for many of the Allied troops, who were consigned to unwanted months in the midst of red tape and demobilisation on an unprecedented scale.

One soldier later wrote: “We had little time to think about getting back to Scotland while we were in the trenches, but it was hellishly frustrating to know the fighting had stopped, and yet we were stuck.

“When Christmas came and went, we wondered how long it would take. By the time spring came, there was a real sense of frustration and even grievance.

“And it led to unrest.”

Part of the problem lay in the structure of the demobilisation scheme which was drawn up to oversee the rapid reconstruction of the UK’s industry.

Coal miners came first in this programme and the Gordon Highlanders had a considerable number of men from the collieries in their ranks.

The official diary of the 1st Battalion recorded that its initial demobilisation party “40 strong, which left for home on December 28 1918, was mainly made up of miners, while the first draft of the 5th Battalion, which entrained on December 11, consisted of 34 men, all miners.

“Most troops did not worry too much about the miners. They did, however, find it unfair that large numbers of men of other categories should be released before men with longer service.

“This was their chief grievance. First in, first out, seemed to them the fairest principle, though if that had been put in force from the start of demobilisation, it would have resulted in even more unemployment than actually occurred.”

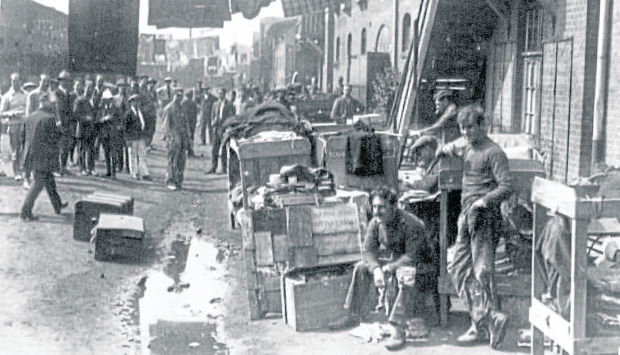

Amid the often chaotic scenes across Europe after the Great War, there was little coherent pattern to those awaiting their release documents.

Among those who had became the enemy overnight were the crew of the Aberdeen ship Rubislaw, which sailed into the German port of Hamburg days before the outbreak of the conflict.

They spent the entirety of the First World War in a prisoner of war camp, interred alongside around 4,500 or so other unfortunate souls in the heart of Germany.

The 18-strong crew, and about 32 other Aberdonians, who were used to life on the open sea suddenly found themselves incarcerated in a foreign land and yet their collective spirit was undimmed by their ordeal.

Indeed, they were a resilient group and, as the months passed and they adapted to their circumstances, they gradually transformed their barren landscape into flourishing gardens.

Then, when they finally returned to the north-east, they brought these horticultural skills to good use and highlighted the fortitude which they had shown during years of captivity.

Elsewhere, the majority of Gordon Highlanders were demobilised by June 1919. However, a cadre from Peterhead, who served in 5th (Buchan and Formartine) Battalion only returned to the north-east on October 14, more than 11 months after the Armistice.

Understandably, following such a long hiatus, they received a rousing welcome and local children were given the day off from school to greet the soldiers as they marched from the train station to the Kirk Street drill hall, where they were treated to a civic lunch and formally greeted home.

At least, they finally reached their destination intact. The same could not be said for the ill-fated passengers on the Iolaire, which was carrying hundreds of men back to Lewis and Harris in the Western Isles on New Year’s Day in 1919, when it smashed into rocks and sank, killing more than 200 servicemen, on the very last leg of their long journey back from the conflict.

It was a terrible disaster which had a grievous impact on the island population, as chronicled by writer Donald S Murray in his new book, As the Women Lay Dreaming.

He said: “The people of the islands suffered the highest losses of any part of the British Isles during the conflict.

“On one day alone, there were no less than nine deaths reported to those in one parish.

“After Iolaire, this led to many households being occupied by single women, either widowed or unmarried, the only clothes hanging in their wardrobes a uniform and unrelenting shade of black.

“They wore this outfit day in, day out, and they did so for decades.”

Occasionally, though, there were happier twists of fate, such as the extraordinary story which appeared in the Aberdeen Journal on Hogmanay, 1918.

It related: “Lieutenant Ronald Hume, one of the region’s prisoners of war, who have just returned home, has had the strange experience of reading his own obituary.

“On April 18, Lt Hume took part in the gallant stand made by the Black Watch at Givenchy, and a series of conflicting reports were received regarding his fate.

“First, he was officially reported as missing. Then, a day or two later, the announcement was received by his father that he had been killed in action.

It was, at least, a Happy New Year for the Hume family. But nothing was straightforward either during or after the hostilities had ceased.