It was the moment the end of one global horror came face-to-face with the height of another.

A procession of discharged soldiers, parading through the gleeful throngs celebrating news of the Armistice, came to a sudden, sobering, halt.

Coming the other way had appeared another military party, Gordon Highlanders with a marching brass band.

In contrast to their colleagues, they wore no smiles, their rifles were reversed and the flag they carried was draped not on shoulders but on a coffin.

It was the Stars and Stripes and it covered the remains of Private Walter Stout, a New Yorker from the American Air Force and a victim of influenza.

He was one of up to 100 million across the globe to succumb to “Spanish” flu in a global pandemic regarded by academics as among the most catastrophic medical events in human history.

Somewhere between 22,000 and 70,000 of those were in Scotland alone.

And the outbreak was reaching the deadliest of its three peaks in the north and north-east in exactly the month the mass killing came to an end on the fields of Flanders.

Young, healthy adults were particularly affected by a strain so virulent they could fall ill on the way to work and be dead by bedtime.

Schools were closed and theatres and cinemas closed to under-14s in an effort to control its spread.

A journal reported on families losing three or more members and one November 11 court report tells the tragic tale of a young man locked up after being rendered so delirious that he took a knife to the throat of his beloved two-year-old daughter.

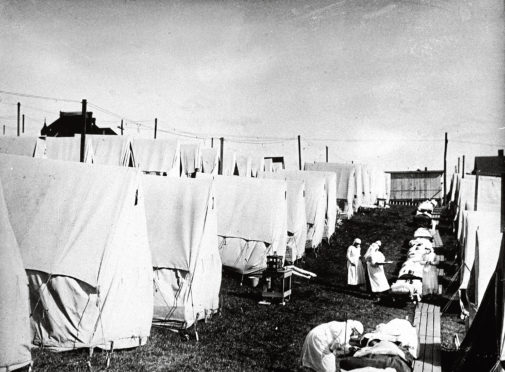

Aberdeen was not lacking in medical facilities at the time – the Ist Scottish General Hospital welcomed up to three ambulance trains a week from the front.

Red Cross vehicles had “become as common on the streets of the city as the Corporation tramcars”.

But doctors were overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the flu – not least because so many of their number were on the front line themselves.

So, along with the war that raged as it took hold, the influenza robbed an entire generation of its potential.

And yet there was – at the time and to some extent since – a strange reluctance to talk about or properly acknowledge such an enormous catastrophe.

A recent study of the issue published by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh looked at the possible reasons.

“The Great War had been such a traumatic experience that the authorities, and the general public, could take no more tragic news and the result was an uncanny silence,” authors Professor Tony Butler and Dr Julia Hogg suggest.

“Scotland had its full share of suffering but, strangely, the calamity had little effect on the public consciousness and the memory of what occurred rapidly faded.”

There is some evidence that a public “weary of fatalities” was perhaps deliberately shielded from the worst by the media of the age – at least one newspaper carried a regular joke column on the subject.

The study quotes from the diaries of a solder in East Africa who talked of rumours that this was “THE END: that a God weary of war had determined to wipe humanity off the world by means of a plague more fatal than man’s destructiveness”.

“Perhaps the idea of the pandemic as retribution for the folly of the Great War occurred to others,” the modern medical experts speculate, “and was so frightening that there was another reason for pushing the whole episode into the limbo of ‘the world’s collective amnesia’.”

Private Stout, who was moved from a training centre in Montrose to Aberdeen’s Albyn Place military hospital after contracting pneumonia but died 10 days later, was the first United States serviceman to be buried in the city – in a headstone-less lair of Allenvale Cemetery.

Records suggest his remains were later repatriated.

Remembering his story and those of the millions more who died in the outbreak may now help us prepare better today for new outbreaks.