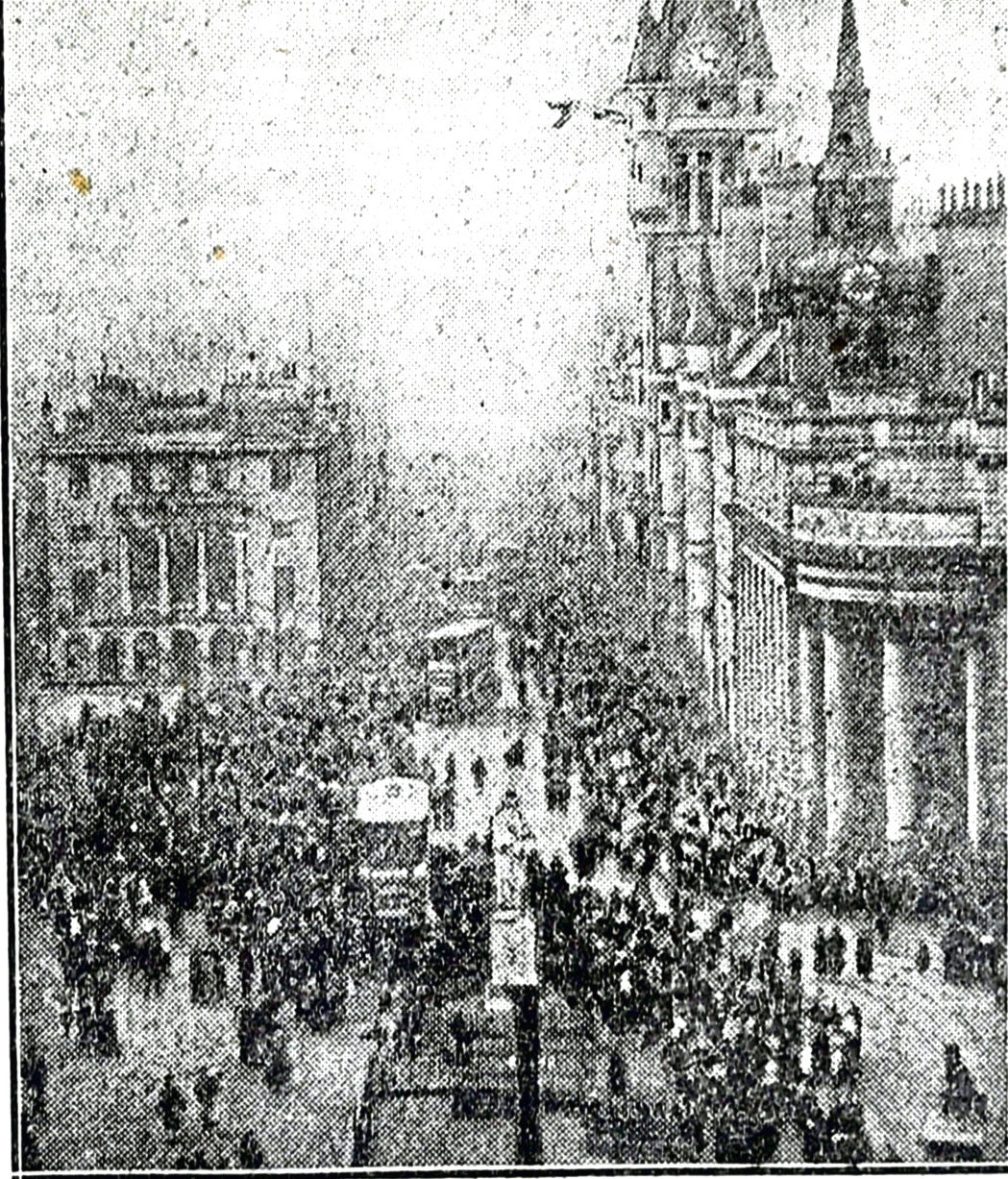

When Sir James Taggart, Lord Provost of Aberdeen, took to the townhouse balcony at midday on November 11, it was to hail a “glorious victory” that put the country “on the verge of peace”.

This though, he cautioned, was not the time to “lose our heads”.

“Let us be calm in the hour of victory, for we have a gigantic task of reconstruction before us,” he urged the throng below.

They might have guessed what he had to say, but it is unlikely a single soul heard a word, such was the cacophony of celebration already echoing across the entire city.

It had begun an hour earlier when hundreds gathered in anticipation at the Aberdeen Journal office in Broad Street, and erupted as a red, white and blue placard was put out, confirming the signing of the Armistice.

Immediately, those inside that office recorded in the following day’s paper, “from the docks and the Albert Basin there arose a tornado of sound” from the hooters and sirens of the boats in the harbour.

And added to the barrage of sounds was one silenced by decree since Hogmanay of 1914: the ringing of the Great Victoria and other bells.

The peals quickly spread all across the north and north-east as the telegrams bearing the news arrived in towns and villages.

Peterhead witnessed “great manifestations of joy”, bunting was run up in Buckie and Dingwall was among places to hold processions.

It was by no means the start of a nationwide party. Nairn received the news “very quietly”, Portsoy with “subdued enthusiasm”.

As a correspondent in Cruden Bay noted, there was “no jubilation, the people having memories of the gallant boys who have died”.

City dwellers, perhaps because in part spared the utter agony of losing such a vast proportion of their population, were more exuberant.

The streets of Inverness were filled with “squads of young workers from the railway shops, the Rose Street Foundry and munition works who formed processions carrying flags and singing”.

A “full share” was taken by “the munition girls in their khaki” it was reported – not to mention the “many young Americans” based in the Highland Capital as part of the huge North Sea mining project.

“They are no doubt pleased with the prospect of going ‘way back home’,” one observer noted.

Back in the Granite City, the revellers were just getting into the swing of it as the city and its citizens “literally blossomed into colour”.

Three colours in particular – red, white and blue – as Union Jacks were hoisted everywhere, on cars, trams, shops and homes.

Thousands of smaller ones were waved by people applauding parades of soldiers – all the more vigorously when it was the Gordon Highlanders marching behind their band, flags fluttering on their rifles.

They received a “magnificent reception along the route – cheers after cheer, and many a cheer through tears,” the Journal reported on the reaction of crowds swelled by works and schools closing for the day.

If such scenes surprised Aberdeen, “they also surprised its many visitors in navy blue and khaki who had perhaps hitherto thought Scotland in general, and Aberdeen in particular, a bit stolid”, it quipped. Students, led by drummers “who beat a vigorous rat-a-plan”, joined the procession, among them “none more demonstrative” than those who had themselves fought.

“As darkness fell it was as though a new Aberdeen had come into being,” the contemporary report suggested.

“Wartime restrictions were relaxed, the townhouse clock was striking the quarters and the hours as it had not done since DORA put her finger against the practice,” – a reference to the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, legislation which gave the government wide-ranging emergency powers and ushered in tight restrictions.

The relaxation of DORA’s grip meant not just more sound but more light too, with the end of anti-air raid blackouts no longer required.

“Shopkeepers assisted to give the occasion a festive atmosphere by lighting up in a style that was positively dazzling after three or more years of gloom.”

Equally illuminated, the clock face from the tower of St Nicholas which was “welcomed as only an old and almost forgotten friend could be”.

In Inverness “rockets and other fireworks banned during wartime were let off without hindrance and loud – almost alarming – reports were to be heard occasionally until a late hour.”

Despite some typical November weather “the houses of entertainment without exception were full to the doors” – a “striking reflection of the holiday or festive spirit that was abroad” – though pubs remained shut.

By 11 o’clock the “youthful and more noisy element” had gone home with its “melodeons, mouth organs, monster crow-mills, songs and flags” – “very tired, but still very happy, to the last echo”.

“Thus, outwardly, Aberdeen made a big stride back towards being its old pre-war self last night.”