It was a disaster which had lasting repercussions for generations of people in the Western Isles.

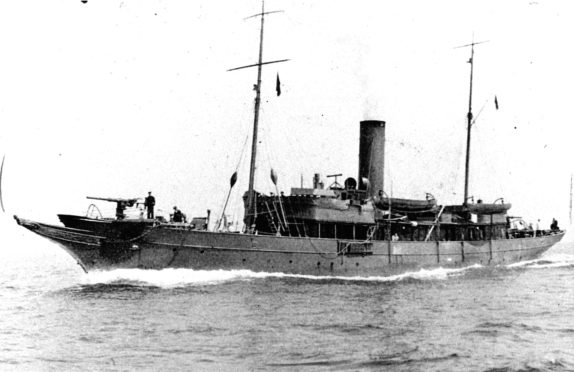

The tragedy of the Iolaire, which sank on New Year’s Day in 1919, with the deaths of more than 200 men, is being commemorated with an exhibition, a series of commemorative events, and other artefacts which will remember those who died almost a century ago.

However, few people have captured the resonance and scale of the catastrophe as poignantly as Scottish author, Donald S Murray, whose book “As the Women Lay Dreaming” brings the story vividly to life.

It affected every member of the community and cast a ghastly shadow over whole communities. Many of those affected could not move on with their lives – such was the impact of so many losses on such a sparsely populated part of Scotland.

Mr Murray has written myriad evocative words to explain how people responded to the Iolaire’s destruction. This is one of these stories.

“Uncle Norman used to draw to entertain us as children. His repertoire was limited. One of his specialities was the whooper swan that swam on nearby moorland lochs.

“He would sketch this quickly, using any available pen and piece of paper, creating what was in effect a cartoon equivalent of the bird.

“Its long slender neck was more upright than its real equivalent, its wings tufted and puffed out. And then there would be the rare occasions when he would sketch the birds that were often found near the swans on the banks of that loch.

“The lapwing – or ‘curracag’ – that skirled as it rose above the nearby peat banks, its distinctive quiff drawn roughly on the page.

“The oyster catcher – or ‘trilleachan’ – with its long strange beak. But most of the time he used to draw cartwheels. Sometimes it would just be the inner hub; occasionally a few broken spokes would appear, jagged and splintered, from its centre.

“Rarely would he draw them whole with rim and felloes intact. In this way, they resembled the shape they were in by the time I grew up on the croft.

“They no longer whirled along the village road, bringing goods from the town of Stornoway to our small village store.

“Neither were they employed to take either peats, our winter fuel, or hay home to our house. Instead, they would lie beyond repair in the barn or, more usefully, forming the foundations of the stacks of hay and oats that stood beside the house.

“They would be weighed down by rope and stone, a fishing net that would thrown upon its summit – a way of ensuring that they would not be toppled by the force of the Hebridean wind.

“The cartwheels performed an entirely different function, providing one of the means by which the lower levels of hay or sheaves of oats remained dry when rain fell and bogged the surrounding ground.

“Yet this may not have been the reason that my uncle drew these cartwheels so often. When he was a child, he saw a large number of horses and carts trundling through the district of Ness to which he belonged.

“In the early days of January 1919, these vehicles brought a large number of corpses – either single or in pairs – to the district.

“They were victims of one of the worst maritime disasters in Britain’s peacetime history, when over 200 men died in the early hours of the morning of New Year’s Day; their vessel the ‘Iolaire’ struck the Beasts of Holm in Stornoway Harbour.

“There was a bitter irony to all of this. Those who drowned on the edge of their native island were returning servicemen, mainly members of the Royal Naval Service, who had survived four years of the war at sea.

“My uncle would have been one of the many islanders who watched that grim procession on the edge of their village; the rotation of these cartwheels a pattern that, for all he never spoke of it, would never leave his mind.”

“As the Women Lay Dreaming” is published by Saraband.