Foo’s yer doos or fit like… if you’re sat there in bafflement then you clearly dinna ken yer Doric.

But if you’re nae bad or chavin awa, the mother tongue of north-east Scotland courses through your blood and no doubt runs through the generations.

The language has an incredibly rich history, yet there was once a time when school pupils would be given the belt for speaking Doric.

Thankfully those days are far behind us, but the mental scars still run deep for those who were taught that Doric was a barbarian language that should not be spoken.

The fight is on like never before to not only preserve the ancient language but champion both the learning of Doric and its cultural heritage.

From the first ever Doric Film Festival set to take place later this year to the rise of Doric taught in schools, and workshops offered at Aberdeen University, the quines and loons of the north-east are ready and waiting to be heard.

For Frieda Morrison, of Scots Radio, it’s not a moment too soon.

As director of the film competition and a fluent Doric speaker, Frieda believes people should be proud of their native language.

She can recall being sent out of the classroom for speaking Doric and is particularly keen to receive film submissions from community groups.

“We wid love to see hunners o’ entries fae a range o’ fowk fae a’ across the north-east o’ Scotland,” said Frieda.

>> Keep up to date with the latest news with The P&J newsletter

The event is set to take place in June with screenings of the best submissions and there are six categories in total.

Frieda is looking for original scripted films of no longer than five minutes, with a £500 prize for winning entries.

Entrants should demonstrate what the north-east means to them with scripts including both Doric and music.

“I used the Gaelic Film Festival as a model and the response so far has been fantastic,” said Frieda.

Prior to setting up Scots Radio, Frieda broadcast in BBC English, otherwise known as a clear enunciated way of speaking.

“I can easily slip between Doric and English,” she said.

“That is the beauty of an indigenous language, it enhances your enjoyment of it.”

Frieda grew up on the north-east coast in a rural community where Doric was widely spoken.

But both herself and fellow pupils were forbidden from using their native tongue in school.

“We were punished and told that Doric wasn’t acceptable,” she said.

“The teacher spoke Doric outside of the classroom but told us off for using it in school.

“That was just the way it was and I think this concept that Doric wasn’t allowed still impacts on people today.

“People need to have confidence in Doric and be proud to speak it.”

But why is the language so important?

Frieda hopes this will come across at the film festival.

“‘Why’ is the big question; we need to show why Doric matters so much,” said Frieda.

“The answer will differ slightly for everyone, but for me personally, it’s about pride.

“I am proud of where I come from and the folk I come from.

“Doric is a noble language and we need to do all we can to preserve it.

“It’s a language for telling stories and it’s a language that needs to be spoken.”

Numerous initiatives are underway at Aberdeen University in a bid to bring Doric both to native speakers and those who wish to learn.

Alistair Heather, of the Port Elphinstone Institute, may not have grown up speaking Doric, but there’s not much he doesn’t know about its remarkable role in Scottish language.

“Here at the institute we’re working on making north-east Scots accessible to all ages,” said Alistair.

“Doric is a byname for dialects of north-east Scots, of which there are quite a few.

“We promote them all equally and at the moment we’re trying to increase the visibility of Doric Scots.

“I’m from south Angus which is the dividing line for Doric Scots; I was raised speaking south-northern Scots.”

Alistair believes that Doric is the final piece in the puzzle for Scotland’s linguistic history, although its promotion reaches beyond heritage to its role as a language today.

“To say someone was speaking Doric was once considered an insult,” he said.

“Doric was the term for a type of barbarian Greek, and began being used by Edinburghers to describe the Scots language spoken by anyone from a rural part of Scotland.

“Fifers and Ayrshire folk were all accused of speaking Doric, an unsophisticated language.

“Now only a community in the Borders and parts of the north-east refer to their own dialects as Doric’.

“There has been a massive turnaround and using Doric is now seen as a mark of respect.

“It is our tongue and a mark of identity.

“Only 40 to 60 years ago, children were beaten with a leather strap for using Doric.

“They would be told not to speak to the minister like that and I think a lot of people still bear those mental scars today.”

The university is currently offering workshops in Doric for both beginners and advanced speakers.

A fresh set of classes started this week and sold out immediately, and workshops will also start in Huntly on January 22.

“We are working towards an undergraduate introductory course in north-east Scots, both online and in person at the university,” said Alistair.

“We also work closely with tourism agencies, so that when visitors come in to the north-east they become aware that they are in a different linguistic area.

“Now the majority of Historic Environment Scotland sites in the north-east have north-east Scots content, either interpretive signs or bairns’ quizzes.

“It has been pretty uplifting to run blocks of classes for primary and secondary schools.

“The classes reveal the hidden abilities in the pupils and encourage them to produce new work in north-east Scots.

“We get great buy-in from parents and grandparents, as Doric homework is something they can really help with, where they might struggle with algebra or chemistry.”

For Doctor Fiona Jane Brown, Doric gives a voice to Aberdeen’s fascinating past.

Raised in Peterhead, Fiona’s parents and grandparents were physically punished for using Doric.

“I used to correct my mum at home and it’s only now that I can appreciate how terrible that was,” said Fiona.

“We didn’t really speak Doric in school, although my parents were amazed that we were taught Doric poetry.

“It’s important to realise that there are so many different sub-dialogues and words used in Peterhead, for example, that won’t be used in Aberdeen.”

Fiona regularly uses Doric to regale visitors on walking tours of Aberdeen as part of her business.

She believes the vocabulary brings the characters to life and educates those who aren’t from the area.

“Local customers absolutely love it when I use Doric because I am speaking something they recognise,” she said.

“Visitors from outside the north-east actively ask me about the language.

“I remember reciting the bothy ballads and people were enthralled by it.

“We need to normalise Doric, that’s the main thing; you should be allowed to use the voice in your head.”

fit’s Scots, fit’s north-east Scots an fit’s Doric?

Scots is the Germanic language spoken around Scotland that arrived around 800AD, and has developed ever since.

It shares much vocabulary with Scandinavian languages – German, Dutch – due to shared Germanic roots and language contact over years of North Sea trade.

It was the official language of Scotland for hundreds of years, and was used by everyone from kings to ploomen up to the Acts of Union.

Scots, like any language, has dialects.

They are usually grouped quite broadly, into north-east, central, insular.

North-east Scots covers roughly from the River Tay to Nairn, but the boundary is porous.

It is marked by pronunciations such as “steen”, for “stane” or “stone”, and “meen” for “moon”, and the use of ‘f’ instead of ‘wh’ for words such as fit (what), far (where) and fan (when).

Whereas in much of lowland Scotland, Scots displaced Gaelic, in the north-east there were centuries of bilingualism.

That is showcased in the number of Gaelic and Scots placenames such as Mounthooly, Pittodrie and Guestrow.

The Gaelic connection is thought by some linguists to have led to many distinctive north-east features.

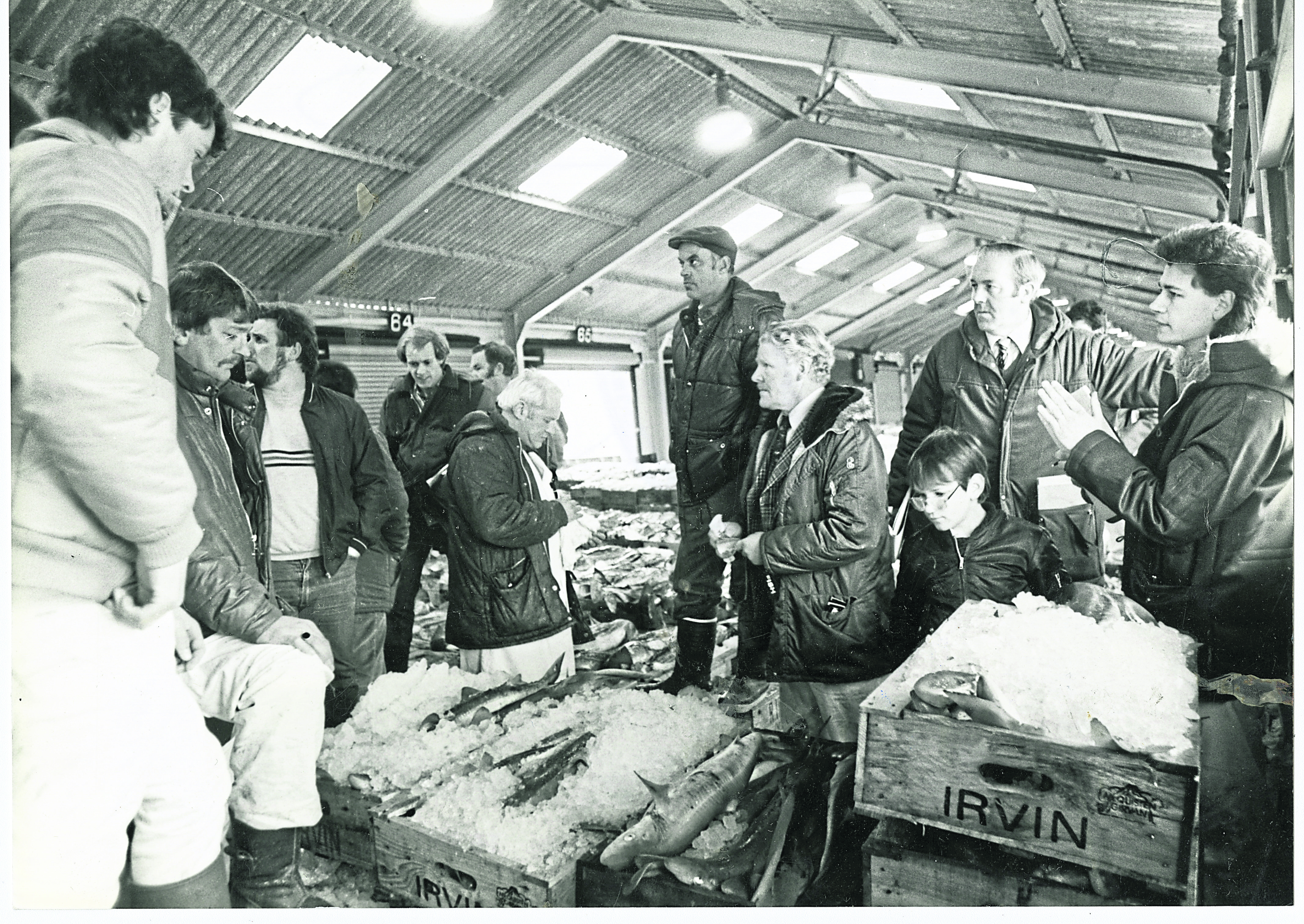

The tight-knit linguistic communities built up through fishing and farming, and the lack of disruption from industrial revolution taking place elsewhere in Scotland, ensured that the north-east developed a very distinct character in its Scots.

The bothy ballads of the north-east form one of the great treasures of European folksong.

Written in the 1800s, they tell in north-east Scots the life of the average farm labourer.