James Addison is never far from the sea, his gaze firmly fixed on the Moray Firth which unravels like a blue ribbon from his vantage point in Cullen.

Despite having just celebrated his 90th birthday, he would, if given the chance, willingly clamber aboard a fishing boat and take to the water once more.

It has been 27 years since James retired from the boats and he is believed to be the last surviving fisherman who fished from Cullen’s waters.

Now suffering from macular degeneration, he believes the sea will remain vivid in his mind regardless of his failing sight.

Fishing has been going on in Cullen for more than 500 years and the village, which once boasted three curing houses, is also, of course, home to the famous Cullen Skink.

The tides rapidly turned against Cullen as the years passed and Seatown, which was the beating heart of the fishing industry, is now a mixture of holiday lets and renovated modern homes.

Although the humble cottage where James grew up is still standing, it is unrecognisable from the two-room but and ben in which he spent his childhood.

Through a mixture of photographs and the passing down of stories, James hopes the traditional fishing industry will never be forgotten.

Its history can be felt across the north-east, from the fishing community of Footdee – known locally as Fittie – in Aberdeen, through to Peterhead, Wick and Gardenstown.

Such communities lived, loved and lost to the sea’s wrath.

Here, some of those who are left tell their stories.

James Addison

“I still have the gansies my mother knitted me, all the women could knit a gansey and they kept us warm at sea.

“They would have a polo neck or buttons at the collar, that was known as your dress gansey.

“I grew up with fishing and it goes through my family for generations.

“I started fishing in 1943 when I was 14 years old and we fished for whitefish out of Cullen or Portknockie.

“During the war we had to be back before sunset and there was usually five of us on the boat.

“By 1944 I went out on the steam drifters and fished for herring.

“For a young loon fishing was absolutely great because it meant we could go places.

“It gave us freedom. I couldn’t swim when I started out in fishing and I didn’t learn to until I was 40 years old.

“I’ve lost two shipmates overboard and that is the worst thing that can happen, because it is a horrible death.

“I remember during the big January storm of 1953, we had a near miss.

“It was a lovely night when we set off from Orkney and just as we entered the Pentland Firth, our skipper decided to change direction.

“We went to Scrabster for another day’s fishing.

“The boat which was alongside us carried on home and it was like a light switch, the weather changed so suddenly – it was horrendous.

“That boat… she was lost.

“That was the reality of fishing and the women had a very hard time of it as well.

“My wife Betty came from a fishing family in Cullen.

“The women would gut the herring before packing them into barrels and curing them.

“I’ve always thought that the women did all the hard work.

“They endured the cold because they did all their work in the open and they worked hour after hour.

“If a fleet came in with a big catch, the women could be working from early morning until very late at night.

“But just as fishing appealed to men, it gave the same freedom to women.

“They would go across to Shetland and work in fishing yards and follow the herring south all the way to Yarmouth.

“That’s where they got better accommodation because they got to stay in holiday homes that had been used in the summer.

“We grew up in complete poverty, but as bairns we didn’t really know that we were poor.

“I miss the comradeship that fishing gave me and the sense of community in Seatown. Now I sit on the bench at the harbour and I think to myself, where have all my pals gone?

“There is no one left.

“I can’t explain how much Cullen has changed and I prefer Cullen as it was.

“It was all local people and there was 23 shops at one time.

“At the harbour alone there were eight grocery shops, two shoe shops and a drapers.

“You could buy absolutely anything.

“I could never leave Cullen, but it makes me really sad to see how different it is today.

“It was the EU that finished fishing off and people went into oil as well.

“I think fishing stands a chance of coming back but it will never be like it was.

“There is a bench down at the harbour in memory of Betty and I often come down here.

“I look towards the sand where she raised our children, they were always playing down here.

“I think it is important that we talk about fishing, about how it used to be.

“We were a real community and we didn’t need material things. I often think that if the people of Seatown were alive today, they would be amazed at Cullen.

“I look back and I think that I have had a really good life.

“If I could live my life all over again, I wouldn’t change all those years at sea.

“It’s where I belong and I’ll be buried next to my wife in the cemetery here.

“It looks out to sea, although I can’t imagine I’ll see much of it.”

Nora Reid

Nora Reid can also remember a time of great poverty where families lived in two rooms with no electricity or running water.

Her home in Westhill in Aberdeen is a world away from where she grew up, but Nora will always consider herself a Fittie quine.

Her 98-year-old mother still lives in the community down at Aberdeen’s seafront, which once existed as a world in its own right.

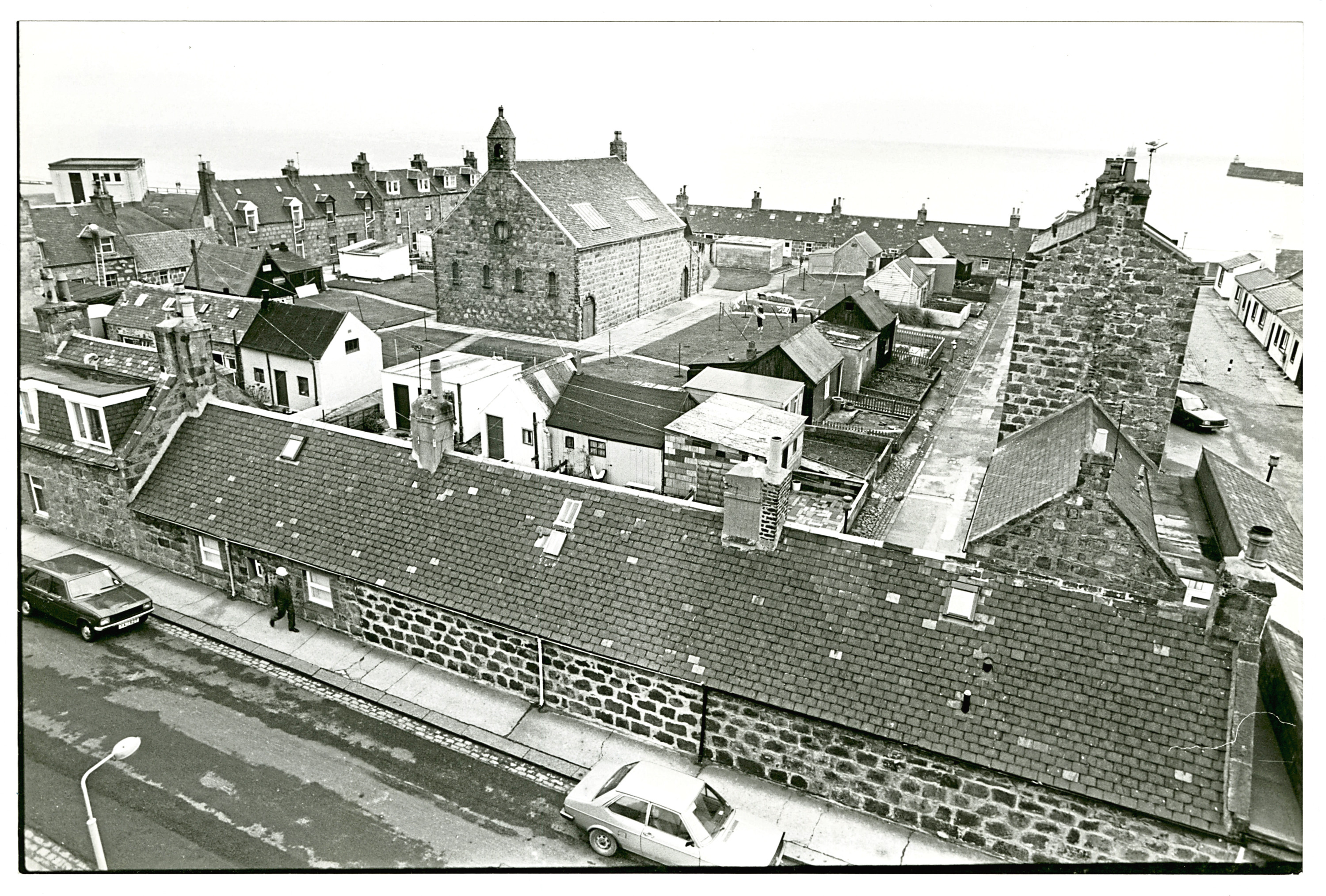

Generations of families lived cheek to cheek in the three squares and relied on a good day’s fishing to get by.

These days you are more likely to run into a bus-load of tourists than a born and bred Fittie resident, and the majority of cottages are now owned by newcomers.

Artists have also made themselves at home in Fittie, transforming the tarring sheds into studios.

For the current residents there is a respectful nod to the past with various projects focusing on Fittie’s history.

The original community was designed by architect John Smith, who was also responsible for Balmoral Castle.

The grandeur of royalty could not be more different to the hardened grit of life in Fittie.

But to many it is a community that must never be forgotten.

The people, the stories and the remarkable spirit of true Fittie folk live on.

“People won’t know me as Nora Reid in Fittie.

“You were always known by your maiden name, by where you came from.

“I’m Norma Webster to Fittie folk because that’s my Fittie name.

“I can remember Fittie as if it was yesterday.

“When the mist rolled in and the foghorn sounded, the gas lights could look quite eerie flickering in the gloom.

“I was an only child, which was quite unusual, but I was never alone.

“That was the thing about Fittie, I’d be round at a friend of my mother’s and I’d be treated as family.

“Everyone was related in some way and we lived at Number 13, South Square.

“You stepped down into the house in those days and the streets were black earth.

“I remember the call of the seagulls and thinking to myself, I am home.

“There were so many children in Fittie, maybe because of the baby boom after the war.

“I always had someone to play with and we protected our territory something fierce.

“I was told stories about people getting stoned if they dared to come into Fittie, but that didn’t happen when I was a child.

“We chased away people who tried to play on Fittie beach though, that was our beach.

“I think it was my great grandfather who was known as the doctor in Fittie.

“He wasn’t a proper doctor but he was the person people ran to if there was a problem.

“You would never play in the square on a Sunday, but my mother pushed the boundaries.

“She’d whisper to me to go and play at the beach and you always had your Sunday clothes.

“They were sized so that they’d last you a good couple of years.

“You’d never hang your washing out on a Sunday either.

“On a Monday we’d go to the mission hall and we’d sing a range of choruses.

“I can still recite John 3:16, for God so loved the world.

“Life was hard and some men did drink, but there was a focus on abstaining from alcohol.

“There were no doorbells and no such thing as locking your door.

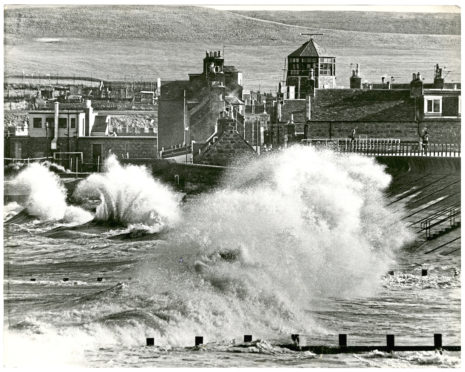

“Before the sea wall was built there was nothing to stop all the spray in north square, which was more exposed.

“The waves would hit the rock and the water would go so high that the spray would go straight down the chimney.

“That happened at Annie Mennie’s, she was stirring her soup on the range and the sea water went straight into the pot.

“I think people left because they wanted more, they wanted bigger houses with bathrooms and more bedrooms.

“In the morning you’d give yourself a rinse down with water boiled from the kettle and that was how it was.

“In the bedroom the bed would be on blocks so the children could squeeze in and go to sleep underneath.

“There were six shops but they were in people’s homes.

“Annie Murray would lift up her window and I’d ask for six ballies of ice cream.

“There was a wooden hut in Pilot Square where you could go for your tea as well.

“My granny would look after people and send me round to a widower’s house with fish.

“That’s missing nowadays, although people still keep an eye on my mother.

“I will keep her in Fittie for as long as I can because it was always drummed into us that you didn’t put old people away in a home.

“I still go down to the beach today and I can find ‘cave rock’ no problem.

“It was a gathering place for us children – a focal point.

“We had a deep respect for the sea and that’s how we were raised.

“My granny would always say we better be home after dark or the water kelpies would get us.

“I like to remember Fittie as it was rather than as it is today.

“My memories are where my Fittie lives, the Fittie I knew and loved.”