As the nation prepares to mark the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings, Neil Drysdale learns how Aberdeen Royal Infirmary prepared for an influx of casualties

It is 75 years since preparations were being drawn up for the Allied invasion of Europe on June 6, 1944.

And, in the weeks leading up to that pivotal moment of the Second World War, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary was among a number of health centres across Britain which devised secret plans to cope with the arrival of casualties from the campaign.

Directors of ARI took steps to ensure they were ready to deal with large numbers of wounded troops, to the extent they curbed admissions to everybody but emergency cases in the north-east.

Following their efforts, the Queen and HRH Princess Elizabeth made a visit to the hospital to meet patients and staff at the start of October.

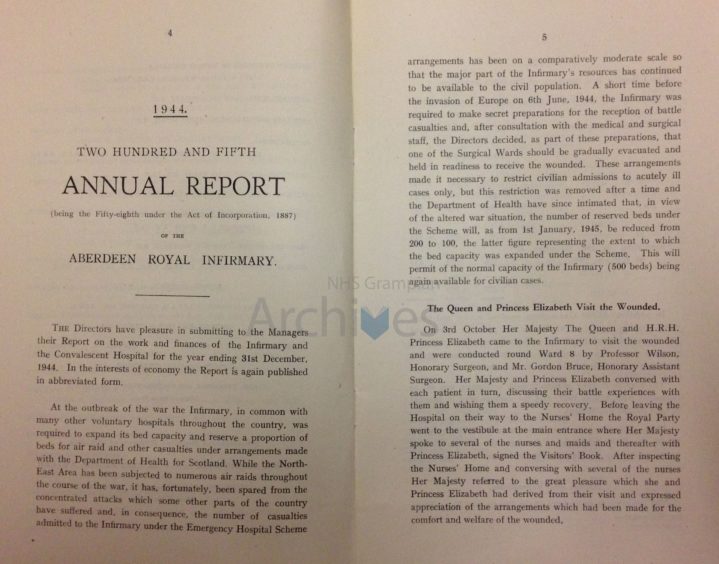

The directors stated in their annual report: ” A short time before the invasion of Europe, the infirmary was required to make secret preparations for the reception of battle casualties.

“After consultation with the medical and surgical staff, the directors decided that one of the wards should be gradually evacuated and held in readiness to receive the wounded.

“These arrangements made it necessary to restrict civilian admissions to acutely ill cases only.”

Fiona Musk, NHS Grampian’s archivist, added: “The managers of the infirmary worked hard behind the scenes to ensure that military casualties were well looked after within the hospital, and to minimise any disruption to ordinary civilian admissions.

“In the time surrounding the D-Day landings, only acute and emergency civilian patients were admitted, but things returned to normal in a matter of months, following the War Office decision to reduce the number of beds which were available to service patients by the end of the year.

“The public were well aware of the various disruptions caused by the war, and would have understood the decisions which were made at that time.”

By the end of the year, the impact of the allied offensive had turned the balance of the war in their favour and the ARI was able to return to something approaching normality.

The directors said: “The number of reserved beds will, as of January 1, 1945, be reduced from 200 to 100, which will permit the normal capacity of the Infirmary – 500 beds – being once again available for civilian cases.”

However, although it was a time of conflict and global hostilities, love blossomed in the Granite City between a wounded paratrooper and the nurse who tended him.

Jan Cooper, from Cockermouth in Cumbria, returned to the UK a few days after D-Day and ended up at the ARI, where he met his future wife, Celia.

She later recalled: “The hospital train with about 60 wounded men arrived at 11am. I was sent to help admit them and to look after the men in the first two beds.

“Then I was called to leave and I went to say my goodbyes, but Cooper had other ideas and told me that he would get me transferred back to ward eight.

“He was a lieutenant in the Parachute Regiment and he was used to giving orders.”

Given their important roles, they could only see each other sporadically, but they became engaged the following January and tied the knot in Ellon in July.

The nurse said later: “Even getting married was traumatic, everything was traumatic at the time. The ceremony was originally planned on July 3, but it had to be delayed.

“Eventually we got married on July 7, but we couldn’t find a place for our honeymoon, so the minister’s sister let us borrow her flat in Edinburgh.”

Mrs Cooper became one of the first married nurses in the country, following new legislation, which allowed wives to go back into nursing or teaching.

Mr Cooper was subsequently sent to Palestine “under cover” and was there for a year and a half working alongside the Palestinian police.

His wife later recalled: “Jan had more escapes there than he did in Normandy.

>> Keep up to date with the latest news with The P&J newsletter

“He was an intelligence officer, but in Palestine you could not defend yourself. They were part of a peace-keeping force, so they couldn’t shoot, but they were shot at.

“He had two or three narrow escapes and some people were kidnapped.”

He finally left the Parachute Regiment in November 1946 by which time he had become a captain.

In May 1947, the couple moved to Brazil where they lived at St Sebastien on the coast and Mr Cooper ran a ranch growing bananas and citrus fruit.