It was one of the pivotal campaigns in military history: an offensive which didn’t end the Second World War, but sparked the beginning of the demise of the Nazis’ domination in Europe.

And the Gordon Highlanders were at the heart of the action when Allied troops arrived in vast numbers on French beaches during D-Day, 75 years ago.

Detailed planning for the invasion of Europe had been going on for years but finally June 1944 was chosen as the time, and Normandy the place, for Operation Overlord.

It was vital to keep the Germans guessing about where the incursion would take place.

Hitler was convinced it was going to be further east, near Calais. Many of his commanders agreed and thought that the landings in Normandy were just a diversion.

The main objective of D-Day was to land enough troops that all German counter-attacks could be resisted.

Shortly after midnight on June 6, 24,000 British, American and Canadian airborne troops parachuted in or landed by glider, tasked to secure bridges.

At daybreak, the landings on the beaches started. Over 160,000 troops landed on five beaches over a 50-mile front.

At the same time, the French Resistance carried out numerous acts of sabotage against German rail, electricity, fuel, ammunition and command systems.

The landings were successful, though at great cost in men and materials.

It took the Allies 20 days to capture Cherbourg and its valuable harbour and a month to capture Caen.

But, by the end of July, General Montgomery was ready to start the drive east, to Paris and on to Germany.

Ruth Duncan, the curator of the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen, explained how the regiment was involved in the operation.

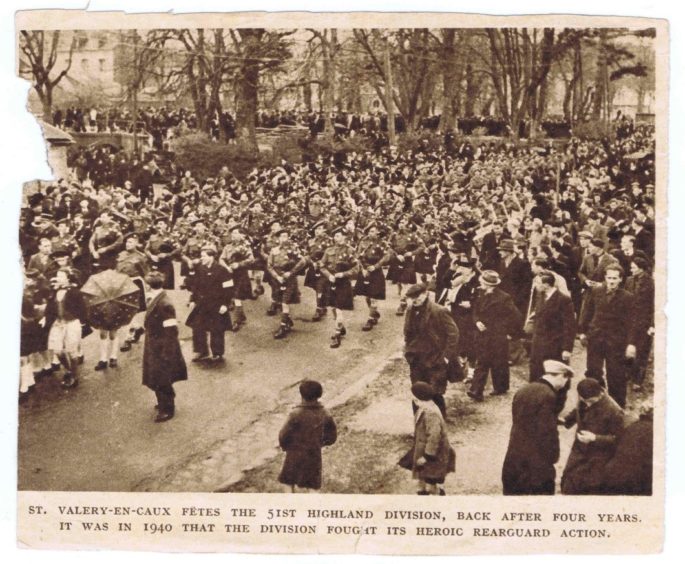

She said: “1st and 5th/7th Gordons were part of the 51st (Highland) Division and landed on June 6.

“2nd Gordons was part of the 15th (Scottish) Division, who landed on June 20.

“1st and 5th/7th Gordons landed on D-Day after the ‘western wall’ had been breached and the leading divisions had started their advance inland from the coast.

“They were the first battalion of the new Highland Division to set foot in France.

“They had trained in Buckinghamshire for this new campaign, practising with new weapons and in new tactics, such as training with the Sten Gun, learning to work with Churchill tanks, mine lifting and laying and street fighting in the bombed and devastated areas of Limehouse in London.

“In May 1944, they were moved to a marshalling area, with the camps ‘sealed’ in the interests of security.

“Inside the camps, troops were furnished with kit and equipment, arms, ammunition and everyone was paid 200 francs.

“Even as late as May 30, the men still did not know where they were going or when they were leaving.”

Ms Duncan added: “The landing, on the western side of JUNO Breach on D-Day, was unopposed but the 5th/7th Battalion had lost its first casualty, Private John Rowe from Lisnaskea in Northern Ireland, who drowned after being swept under a neighbouring vessel.”

While the fight for Caen was going on, both 1st and 5th/7th Battalions were fully occupied to the east and south-east of the city, facing tenacious German resistance for two months.

Small hamlets – Touffreville, Breville, Escoville, Herouvillette, Colombelles – all had to be cleared and it was work that required patience, resilience and courage under fire.

The Gordons and their fellow units may not have gained much ground in terms of distance, but they played a vital role in tying-up – and defeating – German troops who would otherwise have been fighting in Caen or further west.

Ms Duncan added: “The Allied plan called for Caen to be taken on D-Day+1. Bayeux, only 12 miles away, was liberated, but the Germans held on to Caen tenaciously.

“The Allies resorted to bombing to try and dislodge them. On June 7, more than a thousand Lancasters and Halifaxes dropped one thousand tons of bombs.

“Over the days and weeks that followed, there were numerous other raids, together with shelling from the heavy naval guns offshore.

“The Deputy Mayor, Joseph Poirier, wrote that the battle was a 65-day nightmare which destroyed three quarters of the city’s infrastructure, leaving its university, churches and hotels in ruins. Over 1,000 civilians were killed.

“Colonel Charles Usher, a Gordon Highlander, was 53 when he landed in Normandy on June 10 in charge of the Civil Affairs detachment for Caen.

” It was July 9 before he and his staff could get to work in the city and July 18 before the whole of the city was in Allied hands.

“A Second Army report credits Usher for the prevention of panic among the inhabitants:

“It stated: ‘Much credit must be given to Colonel Usher, who… was here, there and everywhere in his kilt’.”

He was awarded the Legion of Honour and the Croix de Guerre fir his work and also presented with a special medallion by the city of Caen.”

Precious few of those veterans who fought in these exchanges are still alive.