Britain’s defence chiefs were on heightened alert in the build-up to D-Day.

So there was consternation in their ranks when a newspaper started carrying clues whose answers were key components of the Allied offensive in Normandy.

The affair even led to the involvement of MI5 and the arrest and interrogation of the setter, whose unique way of creating the puzzles sparked the crisis.

Leonard Dawe, the Telegraph’s crossword compiler, devised his grids at his home in Leatherhead.

He was also the headmaster of Strand School, whose pupils had been evacuated to Effingham in Surrey.

Next to the premises was a big camp of American and Canadian troops preparing for D-Day, and yet security around the facility was lax.

Indeed, there was so much contact between the schoolboys and soldiers that the latter’s conversations, including D-Day codewords, were heard by many of the youngsters.

Mr Dawe, it emerged, had developed a habit of saving time on his crossword-compiling work by calling boys into his study to fill crossword blanks with words. Afterwards, he would provide clues for those words.

As a result, the codenames began appearing in his work on a regular basis, even though he insisted he was unaware they were supposed to be hush-hush.

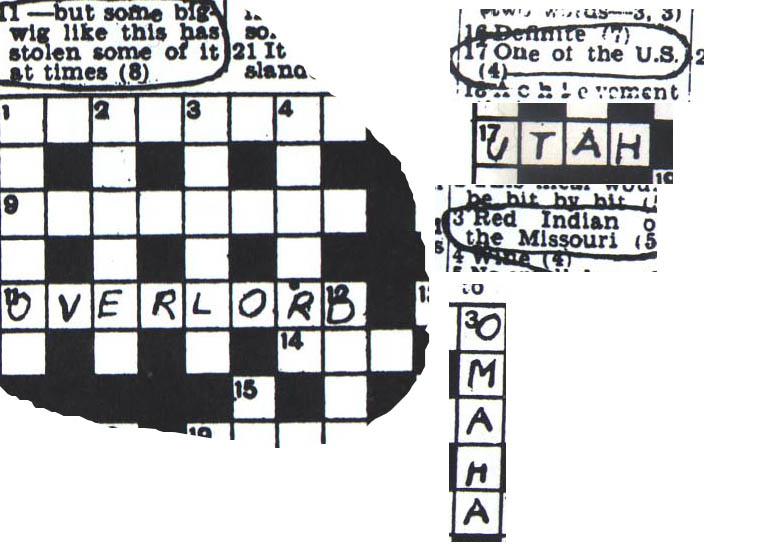

Between May 22 and June 1, 1944, the crosswords were awash with the terms: different puzzles featured ‘Utah’, “Omaha’ ‘Overlord’, ‘Mulberry’ and ‘Neptune’.

MI5 eventually became involved and arrested Mr Dawe at the school and his senior colleague crossword compiler, Melville Jones, at his home in Bury St Edmunds.

Both men were interrogated and left in no doubt as to the serious consequences if they were found guilty of leaking information.

But, eventually, it was decided that they were innocent, although Mr Dawe nearly lost his job as a headmaster over the affair and it rankled with him thereafter.

Afterwards, he asked one of the boys, Ronald French, where he had learned about the D-Day references and was alarmed at the contents of the pupil’s notebook.

He gave him a severe reprimand about secrecy and national security during wartime, insisted the notebook was destroyed, and ordered the boy to swear secrecy on the Bible.

It was only 40 years later that Mr French, by then a property manager in Wolverhampton, came forward and explained that, when he was a 14-year-old at the Strand School, he had inserted D-Day codenames into crosswords.

He believed that hundreds of children must have known the terms.

Fortunately, in this case, careless chalk didn’t cost lives!