Aberdeen University graduate, Helene Aldwinckle, was one of the hidden figures whose crucial code-breaking work at Bletchley Park helped the Allies prepare for D-Day and the Normandy landings in 1944.

She was recruited in August 1942 direct from university, as a junior assistant principal and adapted so quickly to the work in Hut 6 that when the American codebreakers began arriving a year later, she was asked to take charge of their training.

Mrs Aldwinckle, who was born Helene Lovie Taylor in Aberdeen, was awarded the Legion d’Honneur in 2019 by the French Government for her significant service during the Second World War, and died the following year at the age of 99.

But, prior to her passing, she related how she was recruited to join the ranks of those at the Buckinghamshire centre.

This is her story in her own words.

“Before I joined Bletchley Park, I completed a three-year degree course at Aberdeen University (they didn’t do the normal four years during the war).

“I was well known in the University, being on various committees and through

acting and I think that’s probably how I came to be one of a number of

female graduates recommended by William Hamilton Fyfe, Principal of the

University, for interview in London at the Foreign Office.

“I remember it being quite a big thing – I had only ever been as far south as the north of England, to visit an uncle, who was a headmaster!

“So after leaving Aberdeen at quarter to four in the morning, I eventually

arrived in London, during the blackout. The YWCA had no room but the lady

there kindly gave me an address in Gower Street.

I waited for all the ‘all clear’

“Thankfully there was room there, but the landlady didn’t provide meals. I was very hungry as I hadn’t eaten on the train; off I headed in the dark to the Lyons Corner House down the road. They served egg on toast, which was a great thing to have!

“But before it was served, the air raid siren sounded and we went downstairs. I remember it being so bare and cold and standing around for what seemed an age, after which the ‘all clear’ was given in the distance and we returned upstairs.

“After a poor night’s sleep, I went for an early lunch at Swan and Edgar at

Piccadilly Circus and went on to my interview at Burlington House, with the

Civil Service Commission. I didn’t know that I was being interviewed for

something specific – I thought it was for general Civil Service work.

“I recall at least 20 male interviewers around a long table, asking various questions

relating to mathematics, crosswords, interests, languages, etc. The interviewers knew all about Bletchley Park, but I don’t think they were from there and no mention was made of the place in connection with the work I would be doing.

“Afterwards, exhausted, I walked back to King’s Cross for the long journey back to Aberdeen, collecting my handbag from Swan and Edgar’s en route, as I had left it behind. It was some time afterwards, that Burlington House wrote to the Principal of

Aberdeen University to arrange further interviews for selected candidates, with Stuart Milner-Barry, at the Caledonian Hotel in Aberdeen.

Those of us invited were also written to directly – I seem to remember about ten to twelve of us in the room, all girls.

“It was obvious that they’d already selected who they wanted from the London interviews and that these interviewers were from Bletchley Park and making final checks that we were the right sort of people for the job. One particular tall and lean gentleman was present and spoke with me. He commented that he was pleased I’d

come along and that we’d spoken at the previous interview.

I had to leave Aberdeen quickly

“He later gave a ‘thank you’ speech and took me to one side, to confirm that I would be offered government-related work. I remembered wondering how he could be so sure I would be any good, to which he replied ‘I can tell you’ll be alright’.

“I realised then that he must be someone eminent in the organisation. He did warn me that I would receive departure instructions very quickly and would need to leave straight away, and indeed that was the case.

“I was taken on as a permanent Foreign Office Civil Servant, and four of us girls were made Temporary Junior Assistant Principals. I don’t remember if we had a pension, but we were paid between £3 and £5 per month, which was a lot of money at that time.”

“And so, in the summer of 1942, as well as a card being sent to me with instructions, a

letter was also sent to my parents to reassure them that I would be looked after. I caught the train at quarter to four in the morning and I remember my mother being very nervous, asking an Army chap on the station platform to take good care of me – he certainly kept an eye on me until Perth.

“I arrived at Bletchley late at night and went to the telephone on the station forecourt, as instructed on the card. I had been given instructions on what to say when picking up the telephone, to be given the number for Bletchley Park. I had to give my name and a description of myself and was told that someone with a limp would meet me.

It was all very mysterious

“Sylvia, whose surname I never found out, appeared very quickly, with a driver and car, probably within about three minutes! It was all very dramatic, I was put in the back of the car and driven to Bletchley Park and I recall the driver jumping out at the gatehouse

to announce us and jumping back in. We drove straight up to the end, to the

main office, not in the big house but in the outside part.

“We stopped at the last hut and I was welcomed warmly inside by a gentleman, who I had met at the interview in Aberdeen, and he asked if I was prepared to sign the

Official Secrets Act. There was no pressure to do so, other than that he could not offer me the job if I did not sign, but he said: “If you sign, you’re with us”. I read it quickly and once I had signed, he took me to Hut 6 and introduced me to everyone.

“One particular memory stands out, seeing rows of girls, all with similar hair styles. Then one of these girls, a Wren, Agnes Smith, recognised me from Aberdeen University, and said she had voted for me for the Student Council! It was a lovely way to start.”

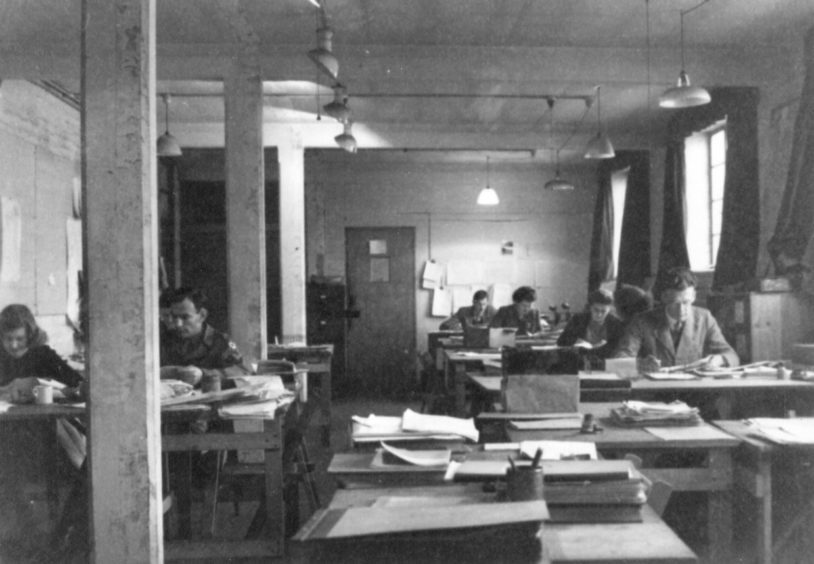

“My work started straight away and I was based initially in Registration Room 1

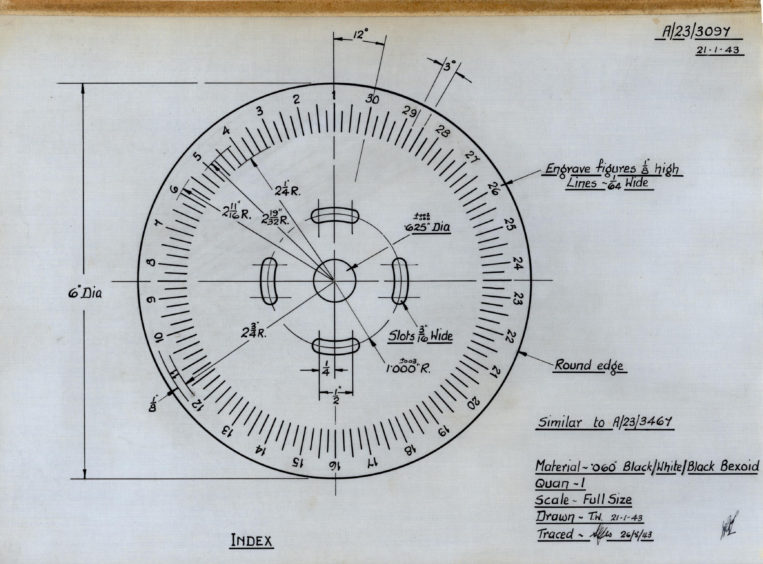

(RR1). We worked on encrypted signals that had been brought in by motorcycle from places like Beaumanor and Chicksands.

“I worked in both RR1 and RR2, for at least a year altogether. There was so much to learn, as I’d never worked on codes before. I sorted the traffic, looked at the call signs to see if there were any repetitions or trends. I was doing a fair bit of analysis work and didn’t have any managerial responsibility.

“After a while, I was invited to lead the training programme for American service personnel. I remember the school building being high up some stairs.

The Americans were full of banter

“I do remember being told by one of the senior people that it was a big job to take on these Americans, but that they were keen to learn. And indeed they were. They were full of banter and used to flirt at every opportunity, for example trying to accompany me to lunch, but it was always in good jest and they were enormous fun and a breath of fresh air in a rather stuffy environment. It was simply lovely to have them there.

“There were about seventeen personnel on the first course and I remember them being a particularly nice bunch. There were fourteen on the second course and in between the two courses I also trained a few British personnel.

“We would instruct them on what was going on at Bletchley, not just my previous Registration work but also wider information from higher up, for which we would have a lecturer. I was very much running the school rather than doing all the teaching – I would do the straightforward teaching (showing them call signs, etc) and calling in other lecturers as needed, from anywhere in Bletchley Park.

“The exciting thing for us was that we’d just got the Colossus machine and

we used to round off the whole programme on the last day by one of our personnel showing them the machine – they’d never seen anything like that before!

“After the courses, I went to work in the Quiet Room in Hut 6, where more

difficult, non-routine work was done. We would often work on longer-term problems and look for unusual trends. Because I had a wider knowledge from my involvement in the course, I was quite suited to the work.

“I went back home to Aberdeen just once, for a week, on the instructions of Jack Winton, who thought I was working too hard and needed a break. Other than that, all I could do was sit in digs in Wolverton, being quite bored.

“Whilst I was at Bletchley Park, we had a PO Box for correspondence and I received correspondence from my fiance that way, because he didn’t have a specific address for me. It was difficult to stay in touch. No one had a straightforward life in those days!

No shortage of interesting people

“I came across some wonderful characters. I remember Hugh Alexander and the rather intense-looking Dennis Babbage, white-faced and who would walk past you, looking as though you might shoot him on the way.

“Of the Americans, I remember Bill Bundy, who went on to become Foreign Affairs Adviser to Presidents John F Kennedy and Lyndon B Johnson, Howard Porter who went on to become Professor of Classics at Columbia University, and I also corresponded with Bill Bijur. I also met some of the Americans subsequently, because my husband worked in intelligence after the war.

“I was married in February 1945 and VE Day was an adventure in itself. I am missing from the Bletchley Park celebration photograph seen in some of the books, as I had gone down to London to celebrate with my husband.

He had previously been with an RAF special duties squadron, dropping SOE agents, and he had arrived back in England a couple of days prior to VE Day.

“He was en route for London, but I had no idea how to find out where he was and he didn’t know where I was. Jack Winton was so good to me, telling me, against the rules, that my husband was staying overnight in Harrogate.

Walking in the dark to the pub

“My problem though was how to get to a phone to call Harrogate, as there was no phone in the digs. The only place I could try was the Galleon pub in Wolverton, which was difficult as it involved crossing a dark field during the blackout.

“Out of the blue, a chap who I knew at Bletchley Park got on my bus and we got chatting. I told him my story and he offered to walk me across the field and collected me from my digs (to the rather obvious surprise of my landlords). As we walked into the pub everyone started clapping, as it turned out he was a musician – he wrote the music for Dylan Thomas’s funeral – and was going to play the piano for them.

“He helped me with the call to Harrogate and that way I was able to arrange to

meet my husband and celebrate VE Day with him in London. So that is why I

am not in the well-known photograph of Hut 3 and Hut 6 people on VE Day.

“I stayed on after VE day and worked on the history of Hut 6, but left before it

moved to Eastcote. I knew I wasn’t going to stay on with GCHQ as, in those

days, you had to leave if you were a woman and got married.

We all knew not to talk about it

“We were all bound by the Official Secrets Act of course and didn’t talk about

our work with anyone, not even after the war. When I first heard about the

[Denis] Winterbotham book [about Bletchley Park], I thought it was awful and shouldn’t have been written, as it let down everyone who had stayed quiet.

“After 1974, when it was published, I felt a little more relaxed about talking generally about Bletchley Park, though I’ve never discussed detail. I think we were all very clear of our responsibility under the Act and that’s why we were shocked when the book

was written. Today everyone seems to know about it.

“I even got a visit from a neighbour’s builder, who had heard I was at Bletchley Park and wanted to talk to me about it. It was quite funny. It‘s interesting that people regard Bletchley Park as something very special, which is rather nice.”

This testimony is courtesy of Bletchley Park’s Oral History programme. Helene Aldwinckle’s Roll of Honour entry is at: