The descendants of 13 north-east men who were killed in a maritime attack in the Second World War will this week mark the 80th anniversary of the tragedy.

On November 28, 1939, the Aberdeen-built ship SS Rubislaw struck a mine off the south-east coast of England and sank within two minutes.

Most of the crew went down with the vessel and only four sailors survived, after they were rescued by a passing mine-sweeper.

The Rubislaw was built by Hall Russell and Company in 1904, commissioned by the owners for the trade between Aberdeen and Hamburg in Germany.

For 10 years, she sailed regularly between the two ports, carrying cargo and passengers, and was a well-known and welcome visitor in Hamburg.

When Britain declared war on Germany in 1914, she was in Hamburg harbour and ready to depart for home.

The ship was impounded, and the crew of the Rubislaw spent the next four years in Ruhleben, a civilian prisoner of war camp on the outskirts of Berlin.

It wasn’t until February 1922 that she sailed once more into Hamburg – where she was given a hearty welcome.

Many of the crew were the same people who had been on the ship before the conflict and had spent the war years as prisoners in Ruhleben.

Trade between the two cities continued up until the summer of 1939, just before the outbreak of the Second World War, when the Rubislaw was taken off the Hamburg route and switched to coastal duties.

And it was while carrying a cargo of cement from London to Aberdeen that she struck the mine.

The tragedy was reported in detail in the Press and Journal, which revealed the heartache and hardships of the families left at home.

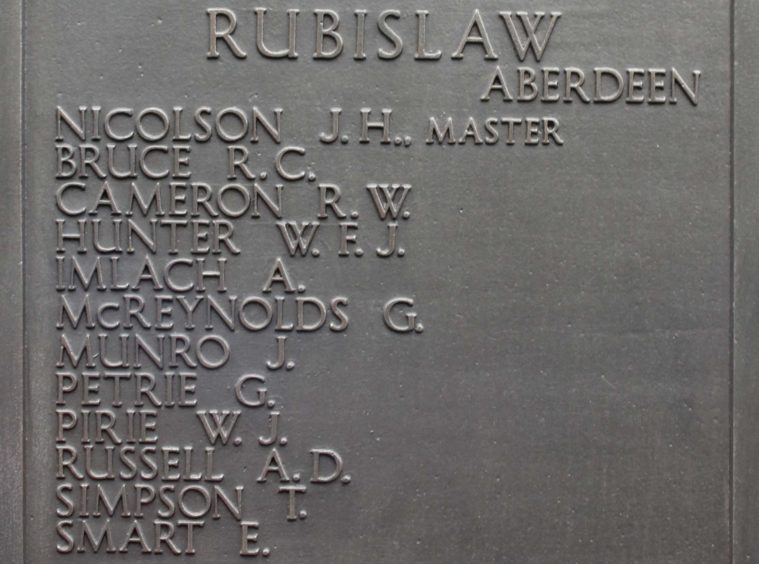

The captain, James Nicolson, had been on the Rubislaw for 14 years, first as mate, then master. He and chief officer Alexander Imlach were on the bridge as the ship sank.

Alexander Dyce Russell was an experienced sailor, and had been with the Rubislaw for four years. His grandson, William Stevenson, spoke this week about the impact the disaster had on his whole family.

He said: When my grandfather was lost with the ship, he left a widow and seven children, two girls and five boys.

“His youngest daughter Stella, his last surviving child, mourned her father until her death in 2014.

“He was among the first of many thousands of men who gave their lives and my family were some of the hundreds of thousands who subsequently bore the lifetime loss of those nearest and dearest to them.”

Margie Mellis, whose book A Crew That Time Forgot explored the vessel’s relationship with Ruhleben, said the destruction of the ship demonstrated how quickly ordinary seamen could become victims of wartime hostilities.

She said: “The sinking of the Rubislaw was a tragic case, but it made me think about all the other merchant seamen and fishermen from the north-east who lost their lives in both world wars, and of their families at home.

“Wives, mothers and children were expecting the men back by the weekend, and many had received messages from the men to that effect.

“George Petrie’s wife was still holding his note in her hand when the port missionary and a representative of the company arrived to break the news.”

The names of those who died are commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial in London, which was created by the Imperial War Graves Commission to remember Merchant Navy seamen and fishermen who have no grave but the sea.

Further information about A Crew That Time Forgot is available at rubislaw1914@gmail.com