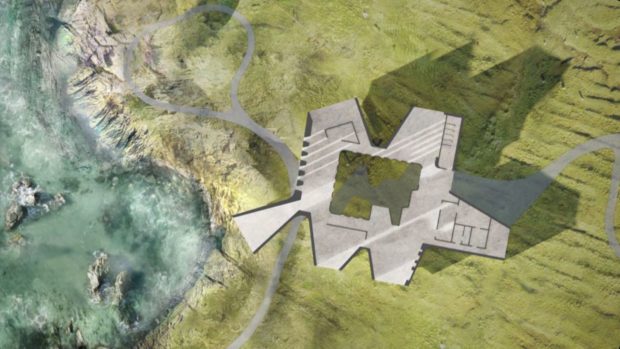

Stunning new images have been revealed that highlight the efforts of a community in the far north of Scotland to build a world-class visitor centre to celebrate the history of St Kilda.

The preferred site in Uig, on the Isle of Lewis, features a dramatic design for the base which will focus on the remarkable history of the UNESCO World Heritage site.

In 2009, four public bodies and the National Trust for Scotland promoted a competition to create and locate a heritage centre in the Hebrides that would celebrate the human and natural environment of St Kilda.

The final decision was unanimous to move ahead with the project at Uig, on a cliff edge where an abandoned radar station once kept an eye on the Western approaches.

When the capital funding required proved not to be forthcoming, the arduous task of developing the venture was left to a local committee.

They have stuck to that task ever since.

And their labours have now been chronicled in a new documentary, which will be screened on BBC Alba on March 3.

Planning approval has been secured for the first phase – A Chiad Cheum – costed at around £2 million. If this is successful, further phases will follow.

Calum Angus Mackay, of Mast-Ard Studio, who directed the programme Oir an Dòchais (Edge Of Hope) said: “Their plans are hugely ambitious.

“It has a total price tag in the region of £5.5 million, with a world-leading architect delivering a concept that will bring great opportunities to remote villages that have struggled with depopulation and a changing demographic.”

The new centre is being designed by multi-award-winning Norwegian architect, Reiulf Ramstad, who has a groundbreaking vision for the project.

He has designed numerous structures and buildings across Europe, including The Whale Visitor Centre and Trollstigen Visitor Centre, in Norway.

Mr Ramstad draws from nature for the design and appreciates the unique qualities of St Kilda.

Since childhood, he has held a passion for maps, and his first visit to the Uig site in Lewis was, in his own words, “like entering dreamtime”.

His designs have taken inspiration from the archaeology of Celtic brochs.

As he said: “We proposed an interior space as a kind of lens, where the distant silhouette of St Kilda would project itself onto a large glass window.”

Iain Buchanan, chairman and director of Ionad Hiort Ltd, a crofter who lives in the village of Mangersta, close to the proposed site, also features in the programme.

Mr Buchanan has led the campaign during the last 10 years and is convinced the ambitious scheme is coming to fruition.

He said: “Like many in Uig, I would like to see an ambitious and bold development plan that can shape the next generation’s future.

“I believe passionately in the concept designs for The St Kilda Centre, but I also realise this project was never going to be straightforward.”

Ionad Hiort – Oir an Dòchais /St Kilda Centre – Edge of Hope is on BBC Alba on Tuesday, March 3, at 9pm.

St Kilda remains one of the world’s most remote and fascinating places

St Kilda is one of the most remote island archipelagoes in the world and has attracted international attention, given its remarkable history and the resilience of those who used to live there.

Situated 40 miles from North Uist, in the Atlantic Ocean, St Kilda contains the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

The largest island is Hirta, whose sea cliffs are the highest in Britain, while three others – Dun, Soay and Boreray – were also used for grazing and seabird hunting.

The medieval village on Hirta was rebuilt in the 19th century, but illnesses brought by increased external contacts through tourism and the upheaval of the First World War contributed to the island’s poignant evacuation in 1930.

The story of St Kilda has attracted artistic interpretations, including Michael Powell’s film The Edge of the World and, every year, thousands of tourists make the formidable journey to breathe in the atmosphere of a place where time has stood still.

Permanent habitation on the islands possibly extended back at least 2,000 years, but the population is unlikely to have exceeded 180 and there were no more than 100 souls enduring the harsh life it offered towards the end of the 19th century.

St Kilda houses a unique form of stone structure known as cleitean. A cleit is a stone storage hut or bothy and, while many still exist, they are slowly falling into disrepair.

There are known to be 1,260 cleitean on Hirta and a further 170 on the other group islands.

At the moment, the only year-round residents are military personnel, together with a variety of conservation workers, volunteers and scientists.

The National Trust for Scotland owns the entire archipelago, which became one of Scotland’s six UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1986 and is one of the few places in the world to hold mixed status for both its natural and cultural qualities.

Parties of volunteers work on the islands in the summer to restore the many ruined buildings that the native St Kildans left behind.

They share the island with the small military base which was established in 1957.

Two different early sheep types have survived and thrived; the Soay and the Boreray.

These animals often embark on incredible and dangerous efforts to find food and the former human residents used to risk their lives to look after them.

The islands are also a breeding ground for many important seabird species, including northern gannets, Atlantic puffins, and northern fulmars, while the St Kilda wren and St Kilda field mouse are native subspecies.