Aberdeen’s Lord Provost has paid tribute to campaigners in the north-east, including a key figure in the history of the Press & Journal, for bringing an end to the slave trade in the 19th century.

Barney Crockett, responding to recent events in the United States and Britain, where statues of plantation owners have been destroyed, said it was important to recognise the “significant role” played by individuals such as James Ramsay from Fraserburgh and James Beattie from Laurencekirk.

Mr Crockett also revealed how journalist John Chalmers launched a campaign in the weekly Journal and the monthly Aberdeen Magazine in the 1780s and 1790s to demonstrate the strength of feeling against slavery in the region.

And he said this led to a “hail of petitions from Presbyteries, the Town Council, and the Incorporated Trades in the city, which supported the abolitionists”.

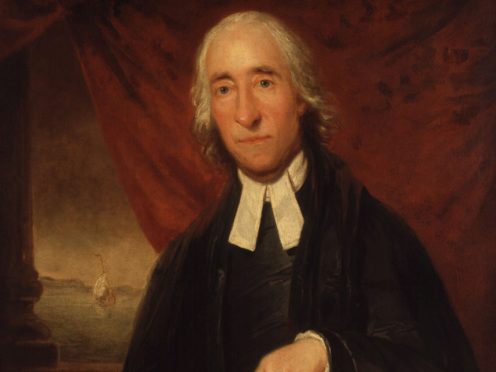

Mr Ramsay, who was born in the Broch in 1733 and educated at King’s College in Aberdeen, was one of the driving forces of the movement.

After his original career as a naval surgeon was cut short by injury, he studied divinity and became an Anglican priest on the Caribbean island of St Kitts.

While in the priesthood, he welcomed African slaves into his church and encouraged them to convert to Christianity.

He also publicly criticised the planters’ maltreatment and abuse of the slaves.

But they responded by conducting a public campaign of vilification against Ramsay, which eventually forced him to leave the island.

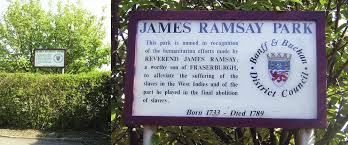

He persevered after returning to Britain, met with other abolitionists, such as William Wilberforce, and was instrumental in the collapse of the slave trade, although he died in 1789 before he could see the results of his labours.

Mr Beattie, who was encouraged in his studies by the parish minister, gained a bursary and a place at Marischal College, Aberdeen, at the age of just 14 in 1748.

He also joined forces with Wilberforce and prepared a petition, signed by the chancellor of Marischal College, before the two men finally met in Bath in 1791.

His pioneering work was rooted less in his publications than in his job as a teacher, where he communicated his deeply-felt horror at the social evil of slavery.

Many of the young men in his classes became schoolmasters and clergymen and preached the abolitionist gospel in the classroom and the pulpit.

His influence snowballed and Aberdeenshire became a centre of abolitionist enlightenment while his friend, Mr Ramsay, is remembered in Fraserburgh by a plaque in St Peter’s Episcopal Church and a public park named in his honour.

Mr Crockett said: “I think it’s right that we are having a debate about the way in which many Scots were part of the slave trade.

“But we should also be emphasising how many others were passionately opposed to it and they became trailblazers for its abolition.

“Aberdeen and the wider north-east was central to this happening and it’s overdue for the efforts of people such as Ramsay, Beattie and Chalmers, who were ahead of their time in speaking out against the evils of slavery, to be recognised.”

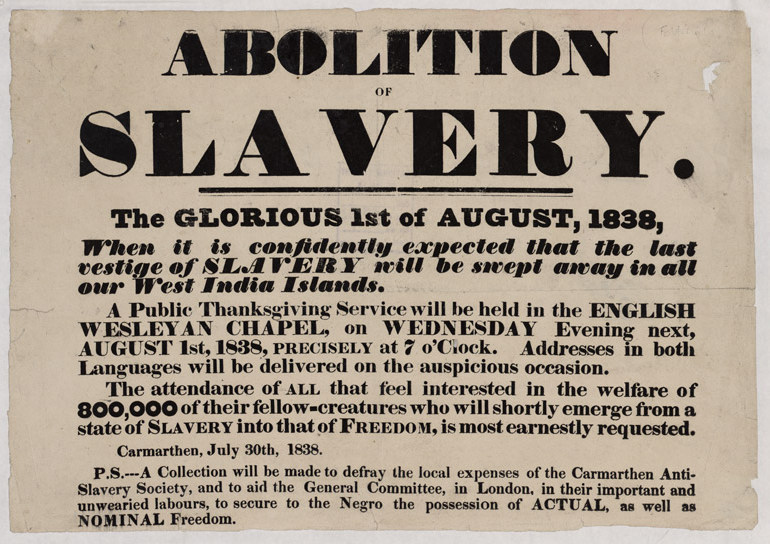

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 abolished the trade throughout the British Empire.