Her story testifies to how she became one of the most remarkable late developers in the history of the Doric language.

Even now, 20 years after the death of north-east writer, Flora Garry, at the grand old age of 100, she remains one of the most cherished figures of her generation.

A redoubtable individual, who meticulously observed day-to-day life in her beloved Mearns, she was a “makar” and a “scriever” whose works are held in high esteem by those who are working to encourage Doric across the north-east in the 21st century.

As Professor Peter Reid of Robert Gordon University, said this week: “Flora was arguably one of the greatest Doric writers.

”I cannot emphasise strongly enough how great a figure she was and still is. I love [another Doric stalwart] Charles Murray, but I venerate Flora Garry.”

He is not alone in his assessment of a woman who never made a big fuss about her talents, and yet created an archive of memorable work which is still gaining new followers across the generations.

So what exactly was the secret behind the success of this Aberdeenshire acolyte?

As a youngster, born in 1900, she was as bright as a button and advanced from Peterhead Academy to Aberdeen University, where she continued to blaze an illustrious trail en route to gaining an Honours degree.

In these days, she would derive pleasure from wandering down the Chanonry, one of the most picturesque streets in the Granite City and, as the writer Jack Webster recalled: “And there, through uncurtained windows, she would gaze in at swell dinner parties, hosted by professors and their families.

”The result, as we would discover much later, was her classic Doric poem ‘The Professor’s Wife’, which highlighted her keen eye for the contrast between the academics and her vastly different background in rural Buchan.”

Eventually, Flora married her own cousin, Robert Garry, a young doctor at Glasgow Western Infirmary, who was the driving force behind the introduction of insulin to Scotland, where it quickly became a life-saver for many people.

He went on to become Regius Professor of Physiology from 1947 to 1970 and it was only after he retired that Flora began publishing the many works she had already created.

As Webster noted: “Though she was writing privately, Flora was an old-age pensioner before her work appeared in book form and we realised what we had been missing.

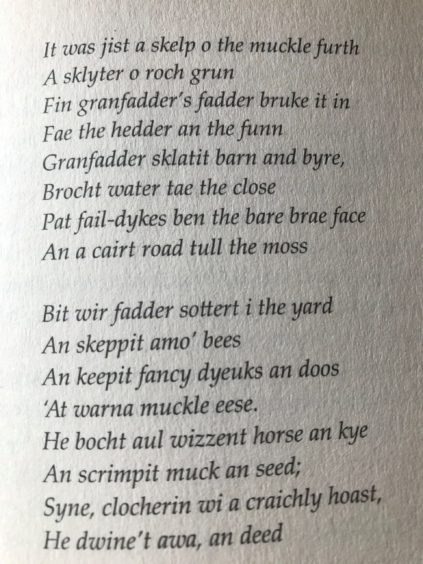

“She perceived beauty in the rolling farmlands of Buchan and there was always Bennachie, away to the west, as well as her own Bennygoak, the title of an early poem.”

The words convey a rich sense of her love for the environment in which she dwelled. And she spoke later about the influence of the natural world on her life.

Indeed, Flora outlined the impetus which lay behind her writing in much the same terms as those employed by “Sunset Song” author, Lewis Grassic Gibbon.

She explained: “I don’t think I could have written about anything else than the land as I knew when I was growing up on the farm there in the middle of Buchan.

“That was what I felt I could write about; it was in me to write about the land and the folk there and the work and the weather and everything there.

“I wanted to write about that. I felt I knew it and it needed to be written about and when I began to write, it had to be in the speech I knew and had grown up with because you have to remember that the Buchan dialect was my first language and I learned English only after I went to school.

”It [the land] was a sort of religion. It was thing they lived for and thought about. It was every day that they were practising this religion.

“Religion, using the word in a different sense, meaning the Kirk on a Sunday was in a way a much more superficial thing than this feeling they had about the parks and crops and the beasts. It’s the land and the work of the land and the changes brought about by the work over the generations.

“But it is more than that; there was music in every one of those crafties and fairms, there was somebody who could sing, play the melodeon, play the fiddle and dance.

“And when you think of the generations of labour – toil that we can hardly imagine now – that went to make all that.

“Their ambition was to own a bit of land and then work it and that was made them take these small crofties – family crofts – and they slaved at them and they worked at them, they improved them and added to them but they held on to the land.

“They had determination and they had courage, but behind all that, there was this feeling for the land.

“And there was also the wanting to have a bit of land and wanting to work it and make it produce.”

As with Grassic Gibbon, her message was profound and yet it was resolutely down to earth.

In the grand scheme, only the land endures.