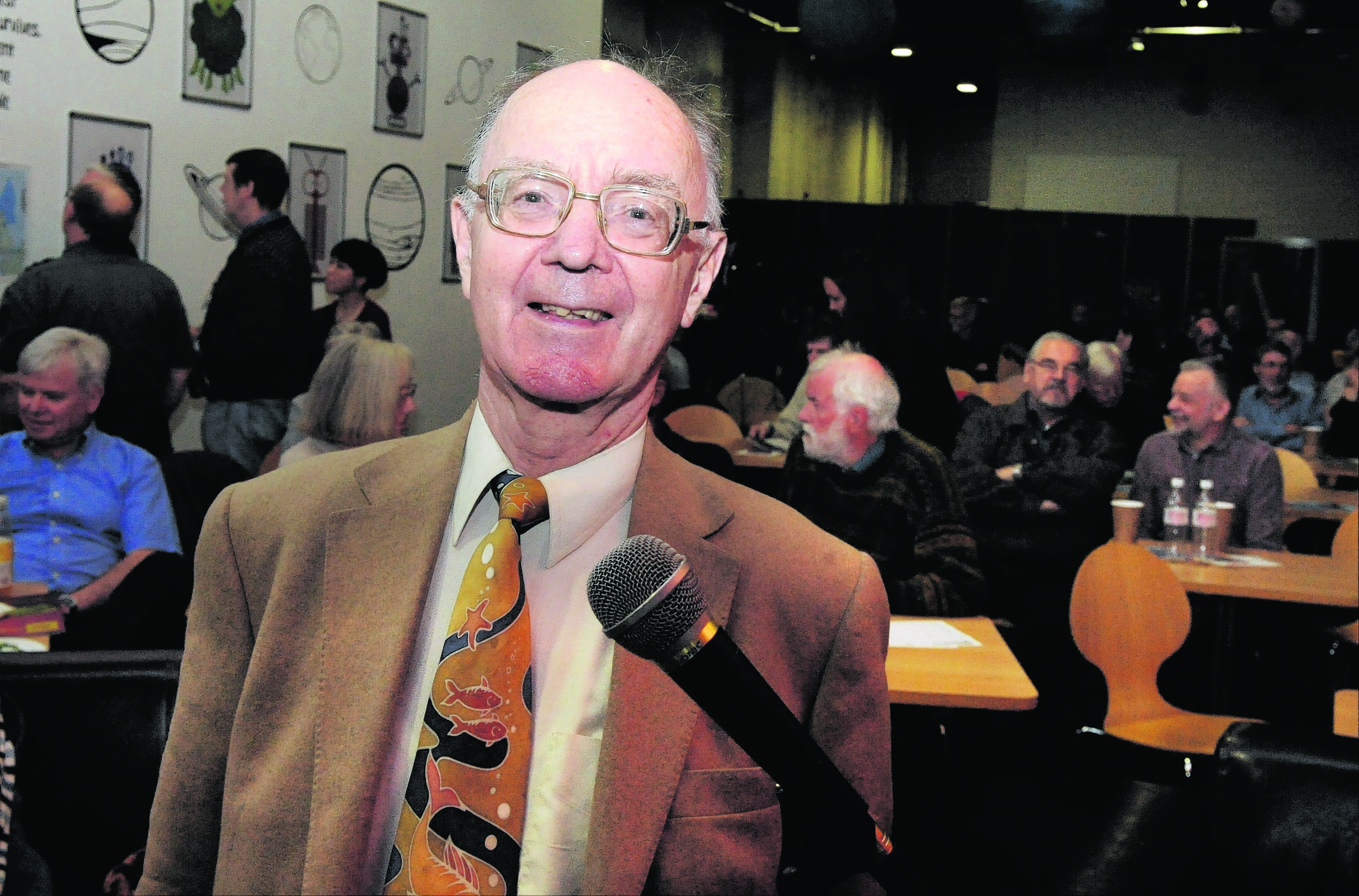

Alex Kemp, professor of petroleum economics at the University of Aberdeen, sifts through the political spin to explain why there has been such wildly varying projections on remaining North Sea oil reserves.

The debate on Scottish independence comes at a time when the North Sea oil and gas industry is arguably at a crossroads in its historical evolution.

Currently, the sector reveals major paradoxes.

Thus field investment is at all-time high levels with the supply chain being extremely busy.

But production has been falling at a brisk rate for some time and production efficiency (the ratio of actual production to the maximum efficient rate) has fallen from 81% in 2004 to 61% in 2012.

The exploration effort has fallen to historically low levels.

Yet interest remains high as reflected in the award of 410 blocks in the 27th Licensing Round. This is an all-time high.

The remaining overall potential has been estimated by Oil and Gas UK to be in the range of 15-24billion barrels of oil equivalent (bn boe).

The Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC) has recently updated its views, indicating best estimates of the remaining potential in the 11.1-21bn boe range but with a significant upside possibility.

These estimates should be seen in comparison with the 42bn boe produced to date.

The present author and Linda Stephen, using detailed financial modelling, has produced estimates of potential cumulative production to 2050 of 14-15bn boe if key recommendations in the Wood Review are successfully implemented.

Production would also continue beyond 2050 on a limited scale.

But projecting production and activity levels generally is difficult because the extent to which the Wood Review proposals relating to exploration, field developments and enhanced oil recovery will bear fruit is unclear.

Thus widely differing views on future production are plausible. DECC has produced very cautious projections of cumulative production to 2050 of 10.4bn boe.

Similarly, differing views are taken on prospective oil prices.

The Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) adopts falling prices over the next few years while others including the International Energy Agency, DECC, and the US Department of Energy contemplate rising prices in the medium term.

All this impacts on the constitutional debate because oil revenues would constitute a substantial element in the GDP and public finances of an independent Scotland.

On the (realistic) assumption that the median line would be employed as the basis for the demarcation of the boundary in the North Sea between Scotland and the rest of the UK, over 95% of oil production would have been in the Scottish sector in recent years.

This proportion is likely to increase in the future. In recent years, the share of total gas production in the Scottish sector has been in the range 46-61%.

The Scottish share of tax revenues has been in the range 85-94% in recent years, reflecting the much higher market value of oil compared to gas.

The tax revenues have historically been large and volatile, reflecting the major variations in oil prices, production and capital allowances.

Recently, they have fallen sharply due to declining production and large capital allowances.

It is quite likely that volatile tax revenues will remain a feature of future activity in the North Sea.

But the uncertainties surrounding the key factors determining them permits differing views regarding their overall size.

The OBR projects continually falling revenues based on relatively low prices and production, while the Scottish Government foresees a revival of these revenues based on higher prices and increased production.

The UK Government has highlighted the problem of reliance on volatile oil revenues for a substantial element of budgetary requirements, while the Scottish Government has emphasised the use of a stabilisation fund to deal with the volatility problem.