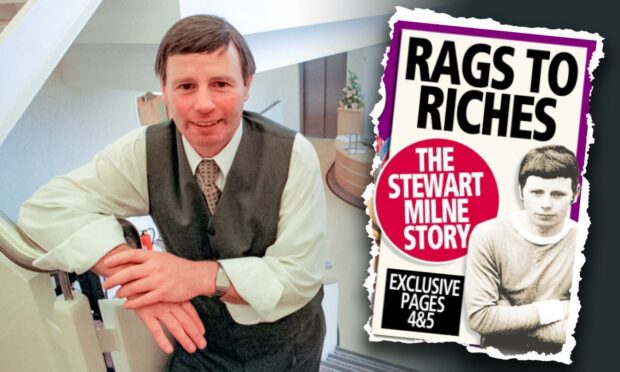

With Stewart Milne announcing his retirement, we searched our archives to find Moreen Simpson’s epic feature on the businessman’s rags to riches tale.

Originally written in 2004 by the former assistant editor of the P&J, we’re taking a look back at how the multi-millionaire rose to the top.

When the going got tough, the boy from Tough just got going

The year is 1965 and a lonely 15-year-old from the country is living hand-to-mouth at the YMCA in Aberdeen.

He’s later to describe it as the worst year of his life.

The big city was a huge culture shock for the teenager from a tiny village near Alford.

The long-established boarders at the hostel didn’t take kindly to newcomers and delighted in bullying the gawky youngster with the thick Aberdeenshire accent.

However, coming from straight-talking, sturdy farming stock, the young lad was no wimp and soon learned to stand up for himself.

Unhappy in his job at an engineering firm, he day-dreamed of becoming a star winger with his beloved Dons. Little did he know he’d one day rise to become Aberdeen FC’s chairman – and the man some fans love to hate.

Life in the YMCA hostel and many other experiences in his younger life have all gone to shaping the outlook, personality and driving force of Stewart Milne – the north-east’s best-known, self-made millionaire.

It’s a classic rags-to-riches story.

From humble beginnings

Brought up in a wee cottage, Stewart and his four brothers grew up with no electricity or bathroom.

Today, he’s the owner of luxury homes in Bieldside and Gleneagles, a yacht in the Mediterranean and runs the most successful, privately-owned, housebuilding firm in Scotland.

Yet his roots are still deeply embedded in the now crumbling old family home in Tough.

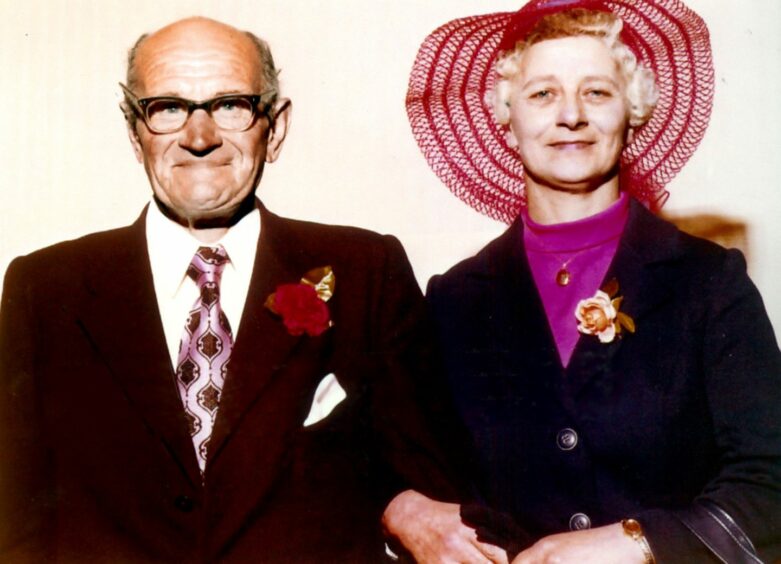

His father, Willie, died when Stewart was 29, but the bond stretches far beyond the grave.

“The main thing he taught me was: ‘Don’t expect to be paid until you’ve done the work – and done it well.’

“He was strict and when I was still at home we would have disagreements and I’d think he was too hard on us.

“I used to see him as thrawn, whereas I thought of myself as determined.

“But after I left home we became extremely close and I could see all the principles he was trying to instil in me.

“And those principles have undoubtedly been a key part of my success. Hard work, commitment, determination and at times, yes, stubbornness.”

A Tough upbringing

Willie hired himself out to farmers for back-breaking work in the fields like draining and ditching.

He was 53 before he married Helen, a local girl in her late 20s, who also worked on the land.

For the next five years Helen gave birth to a son more or less every 12 months – Bill, Sandy, Hamish, Stewart and finally Gordon in 1951.

The three-roomed old schoolhouse was lit by tilly lamps and later – great breakthrough – gas lamps.

The family used a tiny, outside lavatory and bathtimes were in a metal tub in front of the fire.

Each day after school, the boys had their own round of household chores and every weekend they joined their father and mother toiling in the fields.

The young Stewart enjoyed life at tiny Tough Primary school, but at Alford Secondary he spent most of his time staring out of the window thinking about football and girls.

“I suppose I got more than my fair share of the belt for thinking about things I would rather be doing,” he admits, with a smile.

“But that ability has come in really valuable in business.

“I still operate on the basis of giving time to looking forward and imagining what I would like to achieve.

“I’m ambitious for the company. That’s fundamental to the way I operate.”

I thought of myself as determined…”

The little day-dreamer was steered away from academic to technical subjects, which he enjoyed.

But he was hell-bent on leaving school and getting a job, hopefully as an electrician – possibly because he had been without power for most of his life.

At 15 and armed with his leaving certificate, he discovered he was a year too young for an apprenticeship, but the determined teenager got a job in Aberdeen at an engineering firm and a bed at the YMCA.

A start ‘five shillings short’

“I was earning £2-12/6 a week and my lodgings were £2-17/6 a week, so I started off my working life being five shillings short!” he says with a chuckle.

“Every weekend I’d take the bus home to try to persuade mum and dad to supplement my income.

“There was always a bit of negotiation on the Sunday night when I was going back, although they couldn’t afford to give me very much.”

The next year the teenager got accepted as an apprentice electrician and, while doing his day-release City and Guilds, discovered to his surprise that quite a lot of what he had learned at secondary school had actually stuck.

Towards the end of his five years, Stewart and some of his workmates were earning spare cash by doing “homers” at evenings and weekends. That, he says, gave him his first, extremely pleasant taste of working for himself.

His boss told a young Milne he had no chance of suceeding

From a rented flat in Urquhart Road, he moved to Claremont Place, where one of his neighbours, Gordon Bruce, was a newly-qualified plumber.

With the boldness of youth and bursting with enthusiasm, they decided to form their own little company, Bruce and Milne.

The boss with whom he had served his apprenticeship was understandably furious. He told young Milne he had no chance of making it alone.

And pointed out that when he failed, he needn’t bother going back to him for a job.

But this sparky was made of sterner stuff. He was about to put his foot on the first rung of a ladder which – like a powerful magnet – was gradually to draw him to the top.

Overcoming hurdles

However, Stewart had a major hurdle to overcome before starting out on his own – breaking the news to his dad.

“I was quite fearful of the reaction I’d get. I remember getting the bus home and resolving to tell him immediately.

“But it wasn’t until I was leaving on the Sunday night that I finally plucked up the courage.

“His reaction took me completely by surprise. Instead of being hostile, he just said that if that’s what I’d decided to do, I should have a real go at it.

“And he gave me £200 – a huge sum to him – demonstrating how much he was behind my decision.

“That became a major driving force for me.

“I was determined to prove my old boss wrong. But most of all I was determined to repay my dad for showing faith in me.”

Who wants to be a Milne-aire?

Stewart Milne’s multi-million-pound empire began with just £200.

It was a gift from his dad, Willie, to help Stewart set up in business.

Newly-qualified electrician Stewart and his business partner, plumber Gordon Bruce – also armed with £200 – headed for the bank.

The young tradesmen managed to borrow another £400 and the fledgling company Bruce and Milne was formed.

“That was our entire working capital at the time. Neither of us had any idea about cash-flows or any other aspect of business,” says Stewart.

“The money didn’t last very long – even after my girlfriend, Barbara, gave us some more – because we were finding it difficult to get people to pay us for our work.

“Let’s just say for a few months there wasn’t much exotic food or drink about the place.”

Gaining steady work

By the beginning of the 1970s, their company was getting steady work doing tenement conversions.

However, Gordon was newly-married and wanted time with his wife.

Bachelor Stewart wanted to work all the hours God sent to build up the business.

The good friends reluctantly agreed to split their company, with their two employees opting to go with Stewart.

With the council offering whopping grants to install bathrooms in Aberdeen’s traditional tenement flats, demand for the mod cons was growing by the week.

Most companies contracted out the various parts of the work to different tradesman.

Conversions could take as long as three to six months – a huge disruption to the residents, who could rarely move out.

Stewart was convinced there was a better way and gathered together a small team of men covering every trade.

Stewart Milne Construction was born.

Finding a better way of working

“We got to the stage where we could complete a conversion in just three days, apart from decoration. That meant two a week,” he recalls.

“We started on the Monday morning with one and completed it by Wednesday night.

“Then we’d start on the second on the Thursday morning and finish that on the Saturday night. Sunday was used to prepare for the next two conversions.

“Then it came to the point where we prepared all the plans and grant applications as well.”

Householders were delighted with the speedy, one-stop service and were happy to pay premium prices.

Stewart says the young company worked well because of teamwork, planning and people being valued and rewarded for achievement.

They got a good basic wage but could earn more by meeting targets.

“The fundamentals of what I learned then are still important,” he says.

“Never take anything on in a half-hearted way. And never let problems become overpowering.

“Once you’ve committed to delivering something, do the job well and face head-on any issues that arise along the way.”

Long hours away from his young family

Meanwhile, Stewart married Barbara in 1973.

The couple bought a £1,500 flat in Hartington Road and the street was also the base for the company.

Their eldest sons, Gary and Michael, were born there.

Stewart admits that when the boys were little he spent long hours building up the business.

Juggling a relentless work schedule with a young family was tough and he says Barbara’s strength and support were invaluable.

As a young dad, he passed his passion for sport on to his boys, encouraging them to play golf and – of course – football.

The fundamentals of what I learned then are still important.”

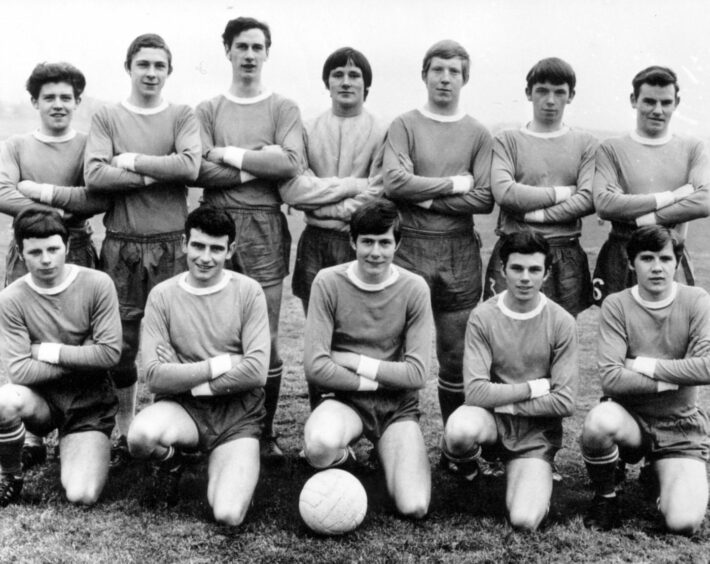

A former Inverurie Loco player who had to give up when he started his business, he loved helping his sons and others develop their skills.

In fact, so much did his enthusiasm get the better of him, he became involved in running Milltimber Primary team, before trying his hand at management with Culter Boys’ Club.

Expanding the business

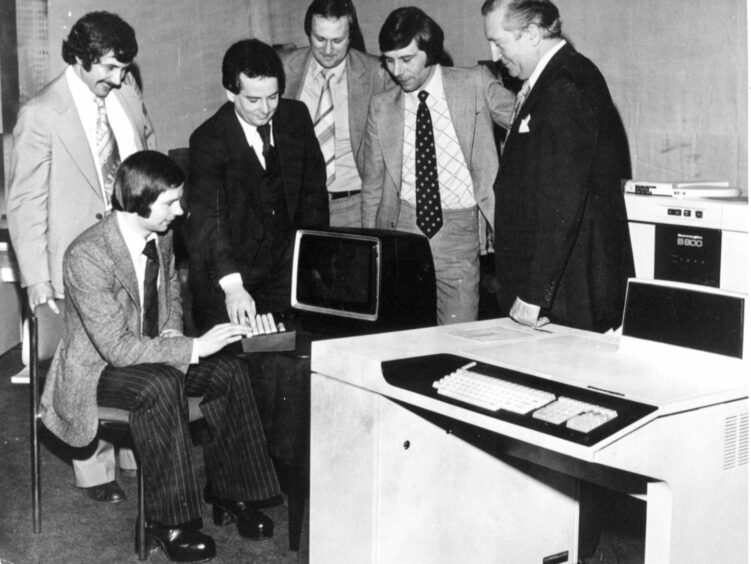

In 1975 Stewart Milne Construction became a limited company with his brother Hamish – a former maths teacher – in charge of finance.

Stewart also head-hunted an engineer with Aberdeen Construction Group, Hugh MacKay, who took on the technical side of the business.

The time was right to expand out of conversions into house-building, opting for timber frames rather than the traditional build.

This proved to be a key to new success.

The natural progression was to build their own houses rather than just servicing other developers.

The first three were built in Kintore in the mid-70s, followed by 30 in Westhill in 1978, then mushrooming all over the North-east.

By the mid 1980s they had three divisions – Construction, House Building and Timber Frame Manufacturing – with a £20 million annual turnover.

Then disaster struck. The bottom fell out of the oil market.

Hundreds of businesses closed down, thousands lost their jobs.

The market collapse

The property market collapsed.

“The next two or three years were extremely painful,” Stewart admits.

“We had to come to terms with the fact we weren’t as good as we thought. Painful decisions had to be made about some staff as well.

I had to face up to the fact I wasn’t as good as I thought I was…”

“And I had to face up to the fact I wasn’t as good as I thought I was and had to develop my own capabilities.”

He emerged from the bleak years knowing the north-east market place would return, but the company would remain vulnerable if it didn’t broaden its horizons.

First they bought Kildonan Homes, then started looking to push into the Central Belt.

This was the move which would put Stewart Milne into the big league.

Building for the future

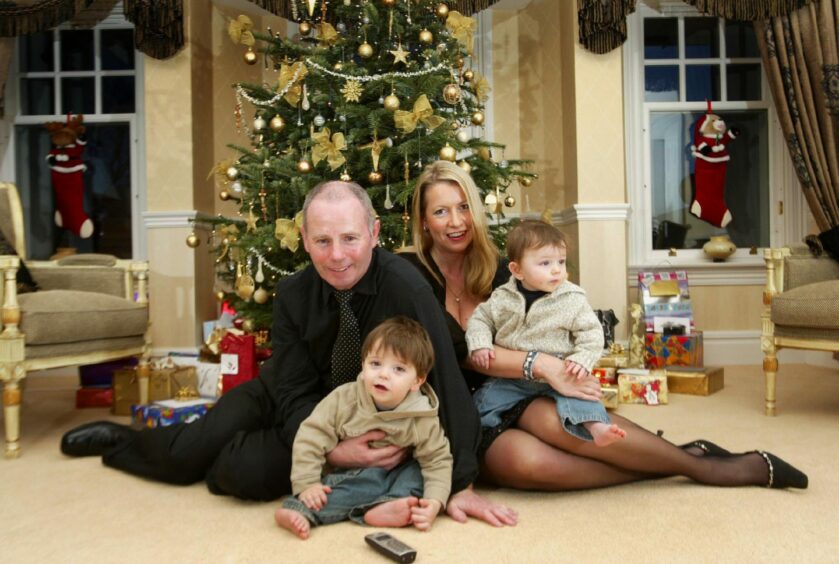

Family and football joined house-building as life-changing passions in the most recent chapters of Stewart Milne’s rags-to-riches story.

The last decade of the century started with the birth of Stewart Milne’s third son, David, in 1991.

The company was going from strength to strength, and two years later came the opening of the new HQ at Westhill to cope with the increasing staff.

Another watershed was reached in 1996 when the group finally grabbed a foothold in the south by buying Glasgow-based Albion Homes.

Meanwhile, Stewart embarked on a new family life with partner Joanna Robertson and her daughters Charlotte, now 16, and Amy, 14.

One of five sons and the father of three, Stewart suddenly found himself surrounded by women.

And Joanna had to suddenly develop an interest in that other love of Stewart’s life – football.

Becoming chairman of Aberdeen FC

In 1994, Stewart joined the board of his beloved Aberdeen FC, becoming chairman four years later.

Fatherhood second time around came with the birth of another two sons – Jamie in 2002, and Charlie a year later.

“I still love to work hard, but I’m essentially a family man who loves spending time with Joanna and all five of my sons.

“I’m determined not to miss any of the childhoods of David, Jamie and Charlie.

“And, you never know – one of them might even be a future Dons star!”

In 2004, the Stewart Milne Group built 1,000 houses a year, producing 10,000 house kits, employing 1,600 people, and another 600 through sub-contractors, with an annual turnover of around £200 million.

Stewart says the single most important factor in the success has been the staff, past and present.

“Without all the people who have contributed over the 30 or so years, the group could not – and would not – be where it is today.

“It’s down to everyone’s endeavours and determination.”

He makes no secret of the fact his dream would be for the business to remain a family concern.

Both elder sons worked for outside companies before joining their dad. Michael, 27, has a business degree and now works for the Homes (North) Division, while Gary, 30, is a structural engineering graduate and is with Timber Systems.

“I always made it clear they would be expected to achieve more through formal education than their father,” he admits, with a wry smile.

“As for my other three sons – who knows where their interests might lie?

“But I’d certainly wish for them to join the business when the time came – if they wanted to.”

From wee loon to multi-millionaire

So the wee loon from Tough is now a multi-millionaire, with a personal fortune of £150 million, according to The Sunday Times Rich List.

“I’m a millionaire on paper, but not in my pocket. It’s all tied up in the company!” Stewart protests with a smile.

He’s got a wonderful house in Bieldside and a new one in Gleneagles – where he stays most weekends – expensive cars and regular holidays on his yacht in the Med, or on

ski-ing trips.

“People look from outside and think everything has been straightforward. But there have been a lot of ups and downs and a lot of hard work put in by many people over the years.

“I hope some real benefits have gone to others as well as me.”

Of course, any joke about his paper millions has a deadly serious side for the chairman of the Dons.

‘I do care about the stick I take’

It’s bound to rile those fans who focus so much of their criticism on him – those who would dearly love to see more cash ploughed into the club. Preferably his cash.

“Look, I don’t have any magic wand that I can wave to solve the Reds’ woes on and off the pitch.

“And I do care about all the stick I take.

“I’m human and have the same feelings as everyone else.

“I go through the same pain and frustration as the fans do at 4.45pm after a bad result.

“Joanna will tell you how much it affects my mood. But for me, the other directors and management at Pittodrie, a bad result affects us and our actions long after the weekend has passed.

I’m human and have the same feelings as everyone else.”

“It would have been easy to walk away because it’s a thankless job and the buck rightly stops with us.

“But that’s when determination kicks in. The belief has to be there that it’s worth going through the barrier and the club will end up stronger, better equipped, and a powerful force again.”

‘It brings everything back into perspective’

He says his priorities in life are family, business and football, but often the pressures of one take priority over the others.

His mother, Helen, died in 2002. After their father died, Stewart and his brothers struggled to persuade her to move from Tough, where they were born, into Aberdeen.

“The cottage was really basic. Mother wasn’t keen to move, but the place simply wasn’t fit for her and eventually she did.

“I had always told dad about how I wanted to build an extension with a bathroom and kitchen. But he wouldn’t hear of it.

“The place is a ruin now. It’s lain empty since 1980, and I must get round to doing it up.”

And yet even today, when he needs to escape from the pressures, the man who has made such a success of improving and creating homes all over the country still drives to the old, tumble-down cottage where he was brought up, and finds inspiration in it.

“It brings everything back into perspective.

“It tends to help me realise the problems are not as great as I thought, and there’s always a way through.

“It’s my roots. And my roots have shaped everything I’ve done.

“Maybe that’s why I’ve left the cottage as it is.”