It’s the news I’ve been waiting my whole life for, and it arrives about halfway through my wellness medical.

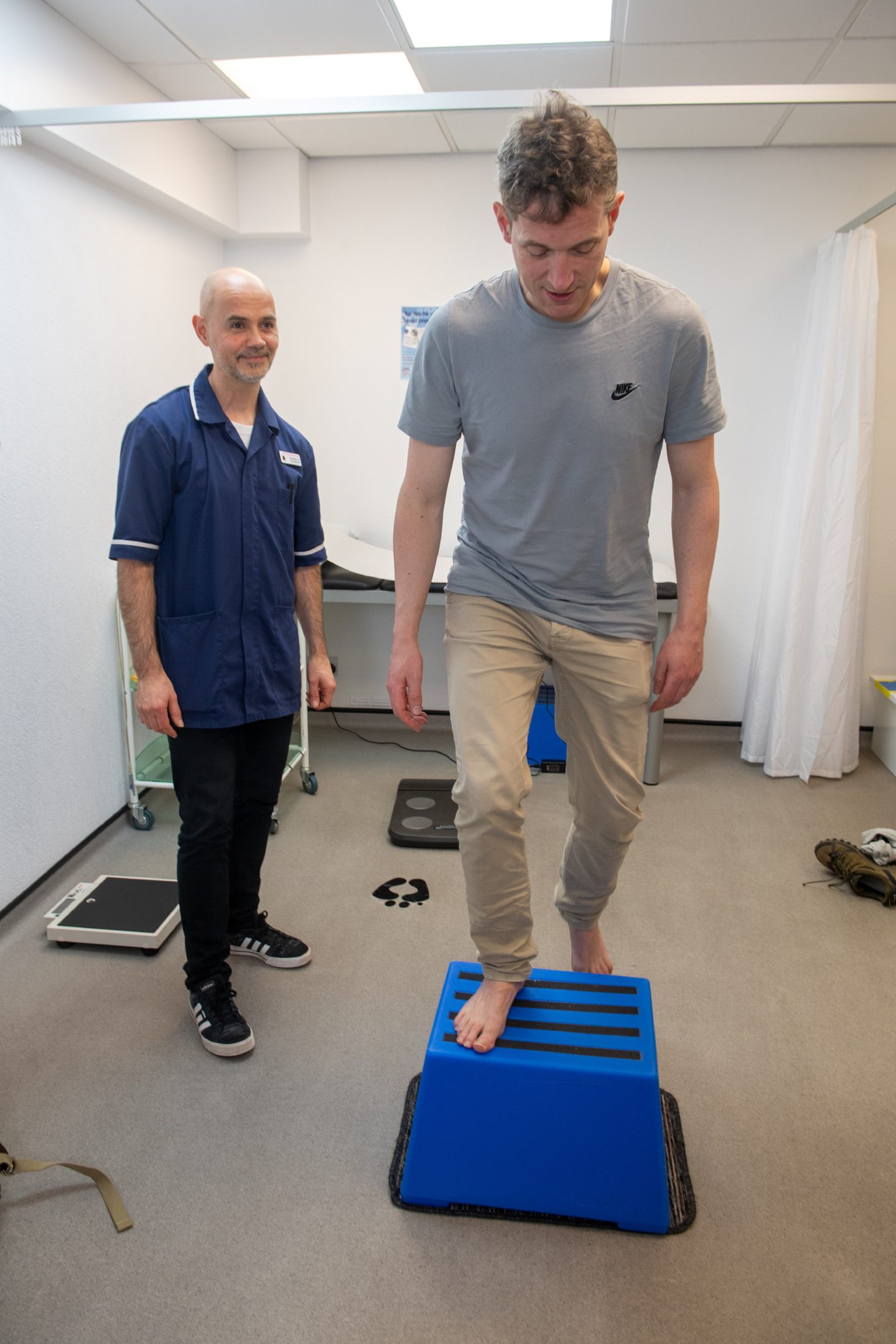

I’ve just finished a step test — repeatedly stepping up onto a small blue box while David Macleod, the nurse in charge of the medical, monitors my heart rate.

David, a softly-spoken islander from Lewis with the reassuring tones of a seasoned healthcare professional, takes the final reading and inputs the data into a computer. A slip of paper is spat out. Breathing hard, I lean in for a closer look.

“This,” says David pointing to the number 44 printed in bold on the slip of paper, “is your VO2 max, your body’s maximum rate of oxygen consumption.”

I’m none the wiser, but David patiently explains that according to the step test I just did, my body is able to consume 44 milliliters of oxygen per kilogram per minute.

He pulls out a chart and shows me it. “For a man of your age, 44 ranks as good,” he explains. “In fact, you are nearly at excellent. For a job in the emergency response teams that fly out to oilrigs, you have to be above 35.”

Wait a minute… I could be an emergency responder? I picture myself hanging out the side of a helicopter, one foot on the skid, jaw jutted determinedly.

David looks at me, fully aware that I have zero other qualifications.

“Yes,” he says, kindly. “Yes, you could.”

A weighty issue for offshore workers

Confirmation that a 47-year-old journalist has passed muster to work offshore might not be the biggest news of the week.

But, considering the news reports over the past year on the expanding waistlines of oilrig workers, it’s perhaps reassuring to know somebody has.

A report this year revealed that the average weight of a North Sea worker has jumped from under 12 stones in 1975 to more than 15-and-a-half-stones last year.

That means one-third are now too heavy to safely board a typical oil-rig lifeboat.

This week, trade body Offshore Energies UK revealed that more than 1,300 offshore workers failed their medicals in 2022, with obesity the third-biggest factor behind blood pressure and diabetes.

For the industry, the weight debate has potentially serious consequences.

“It may well be the case that some people are just too heavy to work offshore,” an oil and gas company health and safety officer told the Press and Journal this year.

‘Significant proportion’ of offshore workers have weight issues

Which is why, as the health reporter at the P&J, I’ve agreed to allow the very nice staff at IMM to put me through my paces with a medical.

Based in Aberdeen, many of IMM’s clients either work offshore or are onshore staff for oil and gas companies.

IMM has seen first-hand the changes to a typical worker.

“We do see people that when it comes to their oil-and-gas medicals, there’s a significant proportion of them that have a weight problem,” says Dr Louise Slaney, IMM’s medical director.

In response, IMM has devised the wellness medical based around something called ‘lifestyle medicine’ – the idea that healthcare should be more than just something for sick people.

Because the biggest health issues in Scotland — heart disease and diabetes — are preventable, lifestyle medicine argues that the best way to treat them is to ensure they don’t show up in the first place.

That’s done by catching early signs of disease as well as identifying lifestyle changes that might improve wellbeing.

What’s more, IMM says the wellness medicals can offer offshore workers sustainable path back to a healthy weight.

“We can show them in black and white that your weight is potentially going to kill you,” Louise says.

“We are now in the second year of doing them and we have seen that people make the effort. It does work.”

Why weight doesn’t always equal unhealthiness

Back in the examination room, David continue to prod and probe me.

I’m getting IMM’s Diamond medical, which is the full service (there are also Silver and Gold versions, which cost less but are not as comprehensive).

David takes blood samples, which will detect all sorts of diseases. As he expertly draws blood from my arm, he reveals it’s often the biggest and burliest oil-and-gas workers that end up fainting.

“Though it’s not the fainting that’s the problem,” he quips. “It’s the falling.”

Next, I’m on the body composition scales, which analyses not just my weight but also my fat and muscles levels. David tells me my body mass index is 25. That’s at the high end of normal, though David does say BMI is an not an exact science.

“It’s a tool to use,” he explains.

For offshore workers, their BMI needs to be below 40. While David says being overweight is the most common issue he sees, heaviness is not always a sign of unhealthiness.

“The offshore guys are pretty active,” he says.

My VIP service, which costs £945, gives me a few extra perks, including a stool sample test kit for bowel cancer.

I take the sample myself when I get back home and then post it to a lab. I won’t go into detail on how exactly I did that. But it didn’t feel particularly VIP.

Time for cigarettes and video games to get in the bath

David gives me a clean bill of health and sends me upstairs to speak to Diane Dobb, one of the clinic’s doctors.

Diane runs through various tests — eyes, ears, lungs and balance. She even knocks me on the knee with a rubber stick in a reflex test I thought only existed in old British sitcoms.

Diane assures me it’s a great way to find out if the body is in tune.

More importantly, she explains the wellness medical’s concept of the ‘Four Pillars of Health’ — food, sleep, movement and relaxation.

Some causes of poor health are out of our control, such as genetics and environment. But we can influence the four pillars, even with small tweaks to out lifestyles, Diane says.

So what’s her advice to me?

Stop smoking the occasional cigarette (“That one is obvious,” she says).

She also says I have an inability to “actively relax”. Playing video games, it turns out, doesn’t count as relaxation.

The prescription? Spend less time on Fortnite and more time in the bath. Preferably with some Epsom salts thrown in for their stress-relieving magnesium.

Sounds good to me.

Offshore medical issues mirror wider population’s

Before I leave, I ask Diane what changes she has seen in offshore workers’ health.

She agrees that some are getting heavier, though she points out obesity is a growing trend through the general population. Plus, unhealthiness is not just confined to people’s bodies.

“You could see it after Covid, the effect that it had on everyone’s mental health,” she says. “People that were drinking before are now drinking a lot more.”

Louise makes the same point. Health issues are increasing everywhere.

“We’re all living longer, which is great,” she says. “But we’re plagued by things like obesity, type two diabetes and high-blood pressure.”

The problem, says Louise, is that everybody knows what is unhealthy — that smoking kills and ultra processed food can make you fat.

Doctors, therefore have to be smarter if they want to punch through. “You really have to give people a program that will fit into their lives,” Louise continues.

She does have one warning. Don’t overdo it.

“If we were all vegans that went out jogging and did 10 hours of yoga a day,” she says, “I’m sure we’d all be miserable.”

For a full breakdown of IMM’s wellness medicals, click here. The Silver medical costs £325, Gold £630 and Diamond £945. Follow up one-to-one counselling sessions are £165.