It sounds like something from a satirical movie and even the mission’s name – Operation Grapple – offers no indication of how many lives it ruined.

And yet, until recently, labyrinthine bureaucracy and official procrastination had led to Dufftown’s Davie Mitchell waiting more than 60 years to receive his Nuclear Test medal, following his period of National Service in the late 1950s.

These were the dark days of the Cold War when Britain, fresh from embarrassment in Suez, was determined to prove it was still a major player in global military warfare.

Dufftown man Davie watched bomb explode in T-shirts and shorts

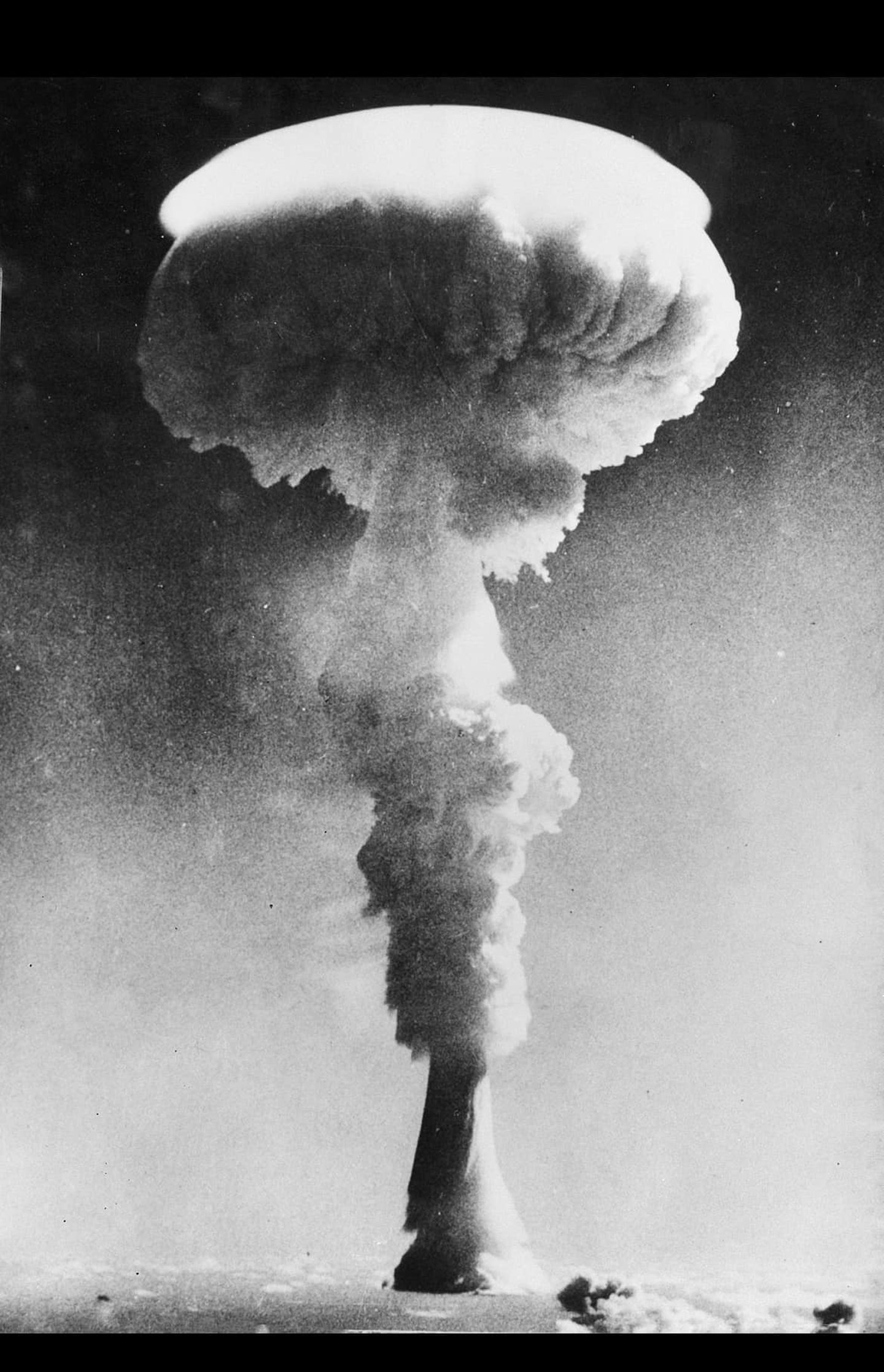

As a consequence, the top brass decided to carry out four series of British nuclear weapons tests of early atomic bombs and hydrogen bombs at Malden Island and Kiritimati – Christmas Island – in the Pacific Ocean in 1957 and 1958.

Mr Mitchell, who is now 87, was among those in the Royal Engineers who stood 20 miles away, clad in shorts and T-shirts, and assured that they were at a “safe” distance.

And even at this juncture, the memory of these events is seared in his brain.

He said: “We were in a holding camp and our postings were put up on a board. Some went to Germany, others went to Cyprus, and some of us went to Christmas Island.

“A couple of lads who were good at football were allowed to stay in Blighty, but the rest of us didn’t have any choice, so that was how we found ourselves in the Pacific.

‘We were told to turn away from the blast and not look directly at it’

“It never occurred to us that it might be an issue that we didn’t have protective clothing. There was pretty much nothing to indicate the power of those bombs [which were significantly more lethal than the atomic weapon dropped on Hiroshima in 1945].

“We were told to turn away from the blast when it happened and not look directly at it.

“But you could feel the heat and, after the explosion, you glimpsed the bones in your own fingers – and I could see the skull of one lad who was standing next to me.”

And, almost immediately, there were grievous repercussions.

In many respects, Mr Mitchell realises he is fortunate to still be alive. In contrast, by the time Orkney-based Roger Kingston finally gained recognition for his involvement in the UK’s test programme, he had been dead for more than half a century.

The youngster, who married his sweetheart Lana in Kirkwall, was not allowed to speak about what he had witnessed on HMS Warrior, the aircraft carrier which served as the headquarters for the operation, but became seriously ill as the 1960s progressed.

Cancer thought to be a consequence of swallowing radioactive water

Eventually, he was diagnosed with advanced kidney cancer, which was thought to be a consequence of swallowing radioactive water while swimming in the ocean.

And despite he and his wife travelling to Aberdeen for treatment, he died in 1968, at the age of just 29, and is buried in St Olaf’s Cemetery overlooking Scapa Flow.

Mr Kingston, whose family were confronted by a wall of silence, was by no means the only fatality. And, as some sought answers, matters grew even murkier amid claims of a cover-up.

Mr Mitchell told me: “A few years later, I developed a skin rash and I told the doctor that I had been at Christmas Island, so he got in touch with the MoD and asked them for my medical records.

“But the answer came back that they had been lost.

Other medical records were ‘lost’ as well

“Well, I went to a veterans’ meeting in Blackpool and spoke to some of the other soldiers. And that’s when I found out that some of the boys had died from cancer.

“There was the lad from Orkney. And one of my mates died of leukaemia. And one of the common stories which emerged was that their medical records had also been lost.

“So, the more I looked into it, the more I realised I was one of the lucky ones.”

The Mitchells are among the most patriotic people you could ever meet. Davie’s father was killed while serving in the Russian convoys with the Merchant Navy on what Winston Churchill described as “the worst journey in the world”.

Davie’s son served in the Royal Navy for more than 20 years. His late wife ran the Dufftown & District Royal British Legion club with unstinting commitment and pride in her work. Yet, they still had to wait for decades.

And even then, there were no grand ceremonies. Instead, they had to apply for it.

‘They told us that the bombs were ‘clean’ and that we didn’t have anything to worry about’

Mr Mitchell said: “I was with the Royal Engineers for two years, as one of the last of the National Service cohort, then I returned home to get on with my life.

“We had heard about the Nuclear Test medal, and my son contacted the MoD to learn more about it. Once we had the information, I provided the details and filled in a form. Then, a couple of months later, the medal arrived.

“I’m pleased that I have finally got it, even though it is more than 60 years ago.

“The thing is that, because we were in the Pacific and not in a conflict, it didn’t count the same as being on active service [such as those who were posted to Cyprus].

“They told us that the bombs were ‘clean’ and that we didn’t have anything to worry about if we covered our eyes and turned our backs.

‘You didn’t question authority’

“But there again, the pilots in the aircraft had to fly back through the clouds of incredible heat and smoke – and a lot of the RAF boys died as well.

“You didn’t question it. We went over there to serve our country. And we did so.”

It was only in 2022 that the campaign for recognition of those involved in Operation Grapple led to the creation of the medal, a commemorative award to honour the contributions of those who – often unwittingly – took part in the exercises.

Sadly, by the time Mr Kingston was posthumously given the honour last November, Lana herself had fallen ill and died just a few weeks away.

These men deserved better

A study of Pacific veterans found that they had a higher mortality rate and were more likely to have cancer than a control group of other soldiers.

And, just as troublingly, it found that the children of veterans were susceptible to more birth defects, and their grandchildren were more likely to have childhood cancer.

Thankfully, Mr Mitchell has been applauded for the many years of community work which he has carried out in Dufftown, including at the British Legion club.

But his efforts and service are at odds with an infamous chapter in his nation’s history.

Conversation