When the Highland Railway Company opened Inverness Station in 1855, no expense was spared in bringing rail travel into the heart of the town.

The modest, but elegant station was a source of great pride for the company, which based its headquarters there.

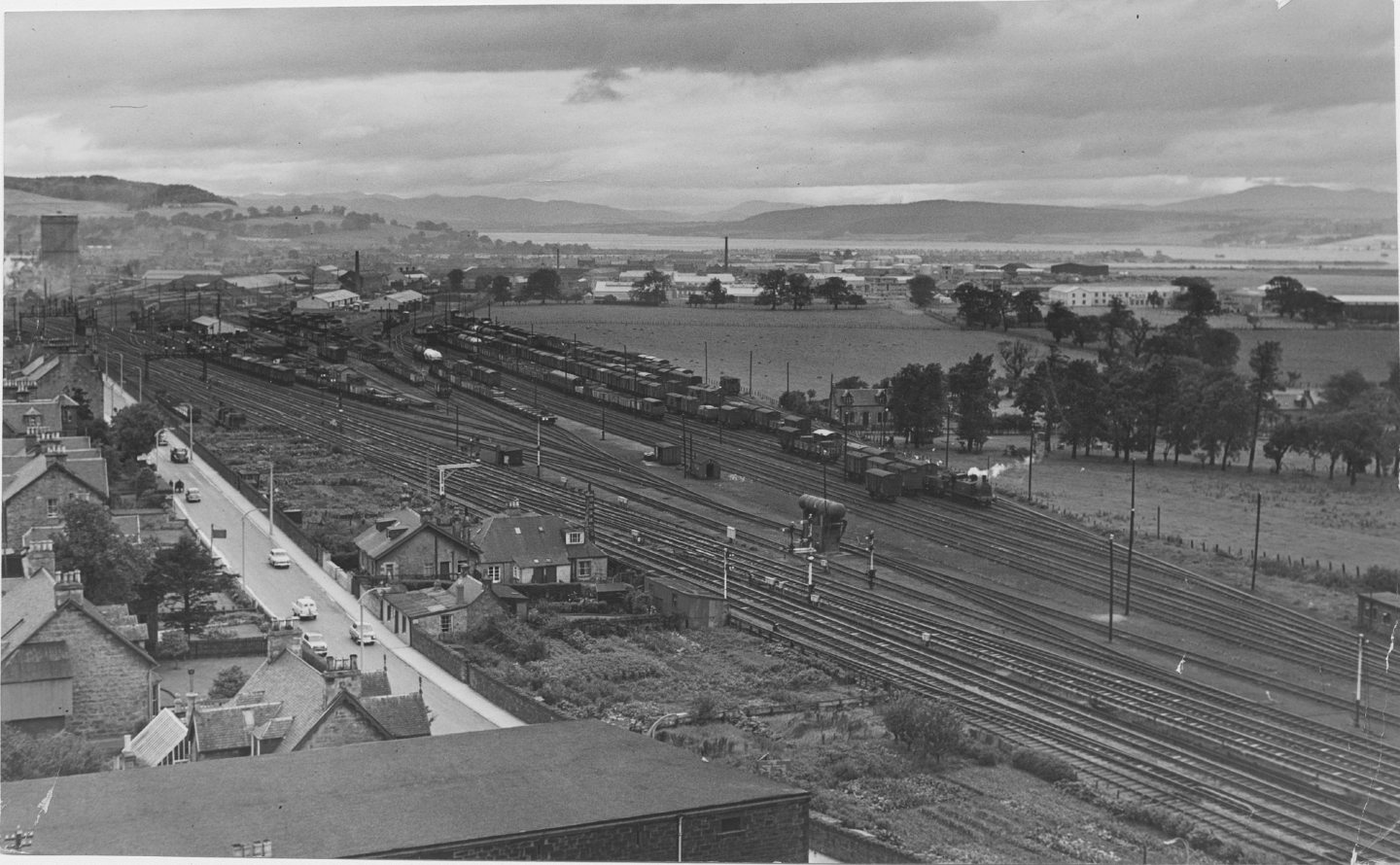

Inverness has long been the capital and crossroads of the Highlands, with its station connecting the city to Perth, Aberdeen, Wick, and Kyle of Lochalsh.

When Inverness Station opened on November 5 1855, it was said “half the population” of the town gathered to witness a red letter day for the Highlands.

Opening of Inverness Station was the first time many people had seen a train

Shops, warehouses and businesses closed to watch the first train leave for its journey to Nairn on the newly-completed Inverness & Nairn Railway.

The train was made up of 30 carriages, many were ordinary goods wagons fitted with benches, to cram in 800 passengers.

The plain wagons were decorated with flags, garlands and flowers, while the locomotive at the front was described as “a mysterious stranger”.

For many townsfolk it was the first train they had ever seen.

A second engine took up its position at the head of the train as one was not enough to haul such heavy cargo.

Both engines, too, were decorated with a dozen flags of various sizes and colours.

‘Monster train’ glided from station to a chorus of cheers

Inverness’ Lord Provost, magistrates and railway directors – including Mr Mackintosh of Raigmore and Mr Fraser-Tytler of Aldourie – took their seats near the front.

The names Raigmore and Aldourie were then bestowed on the locomotives, which were built for the Highland Railway in Leith.

A newspaper report of the occasion said: “It was obvious something extraordinary was in hand.”

Just after noon, a couple of small guns fired, a row of flags were raised, and the “monster train took motion, and amid the enthusiastic ‘huzzas’ of many a spectator, it glided from the station”.

For a full two miles along the route, eager groups of onlookers awaited and gave hearty cheers as the excursion train passed by.

‘People gazed and gawped at passing prodigy’

Meanwhile the hill at Hut ‘o Health, better known as the Cameron Barracks nowadays, was “crowded from base to summit” as Invernessians clamoured to catch a glimpse of the train.

The report added: “It was if all of Inverness had emptied itself to witness the event.

“At every farmyard and point of rendezvous a group of wondering people had assembled, who gazed and gaped at the passing prodigy.

“Even the dumb cattle felt the spell.”

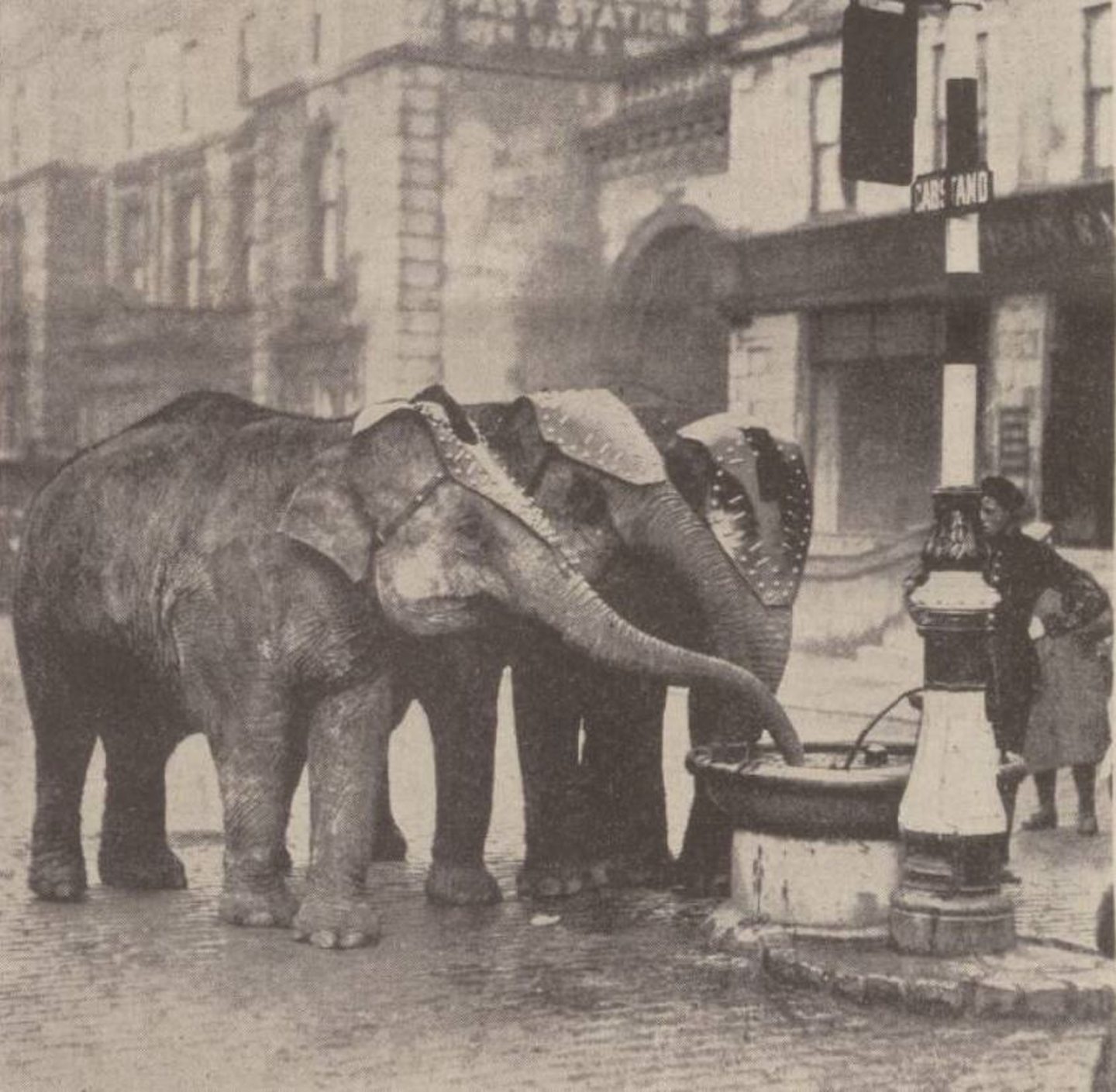

Cows and horses along the line “fled in alarm, kicking violently” as the train thundered by.

Inverness-Nairn line opened for public use on November 7 1855

The first stop was Dalcross where more passengers boarded, the next was Fort George Station near Ardersier.

The journey to Nairn took around 45 minutes, including stoppages, where there was a “most hearty” welcome on arrival.

The train stopped there for nearly two hours while passengers enjoyed, refreshments, amusements, and crowded out local inns and bakeries.

On the return journey, the “outside passengers” were rather more merry and sang songs in loud chorus all the way home.

Drawing into Inverness Station, the train was greeted with as large a crowd as had seen it off.

The following day a similar excursion took place, before the line opened for passenger traffic on November 7.

Inverness suffered during rampant removal of railway architecture in 20th Century

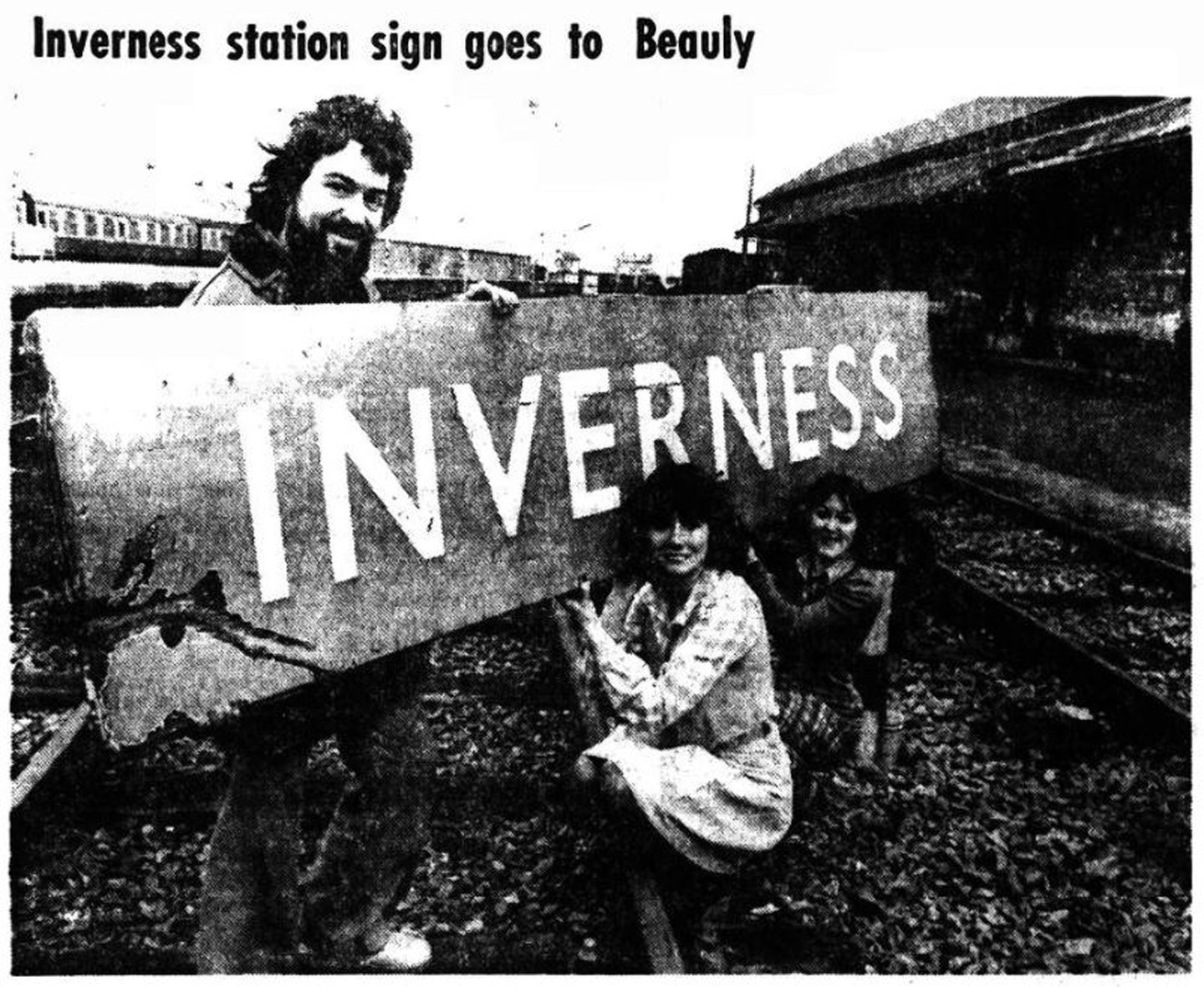

Sadly, little remains of the original Victorian facade of Inverness Station, which was redesigned in the 1960s.

In the mid-20th Century many buildings were deemed incompatible with a modern rail network.

Happily the Lochgorm Works remain, built in 1860, it is now a B-listed building.

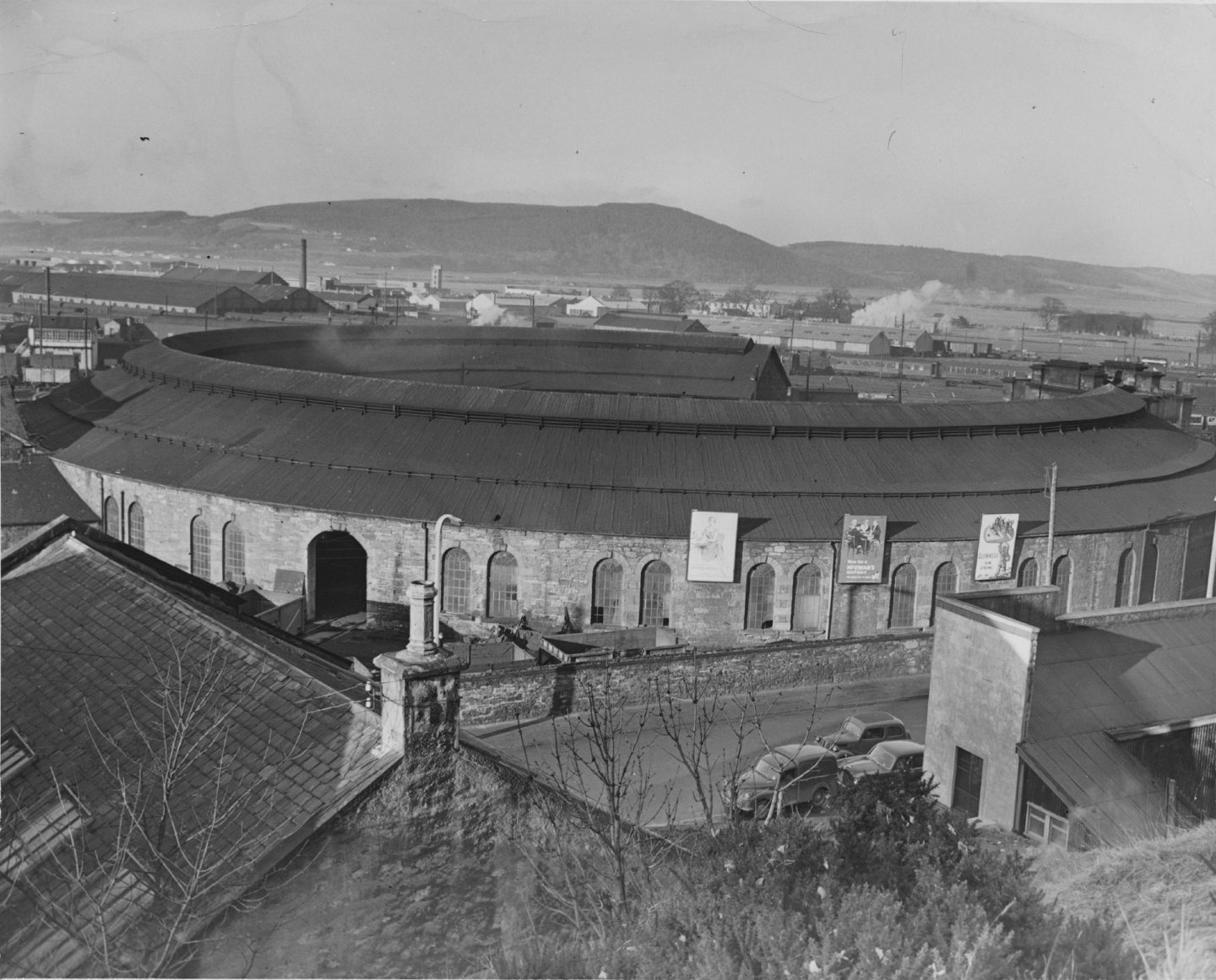

But one building lost was the striking round-house engine shed – its demolition came in the 1960s, a time of rampant removal of railway architecture across the UK.

SAVE Britain’s Heritage, the charity which campaigns for historic buildings, held an exhibition in 1977 called ‘Off the Rails: Saving Railway Architecture’.

In SAVE’s exhibition companion book of the same name, writer Simon Jenkins said: “Britain invented the railway, pioneered its application to passenger travel and built the most extensive network of lines and stations anywhere in the world.

“We also did so earlier than anyone else.

“As a result, Britain’s railways constitute an architectural achievement without parallel.”

SAVE highlighted the swift loss of railway buildings at a time when demolition was preferred over preservation.

While the trend nowadays would be to seek alternative uses for station buildings, this was not so in the ’70s.

Simon added: “No group of British architects have had their work less cared for than railway architects.

“No aspect of British craftsmanship has been less conserved than that of our railway engineers.”

Inverness’ round-house shed was striking landmark for decades

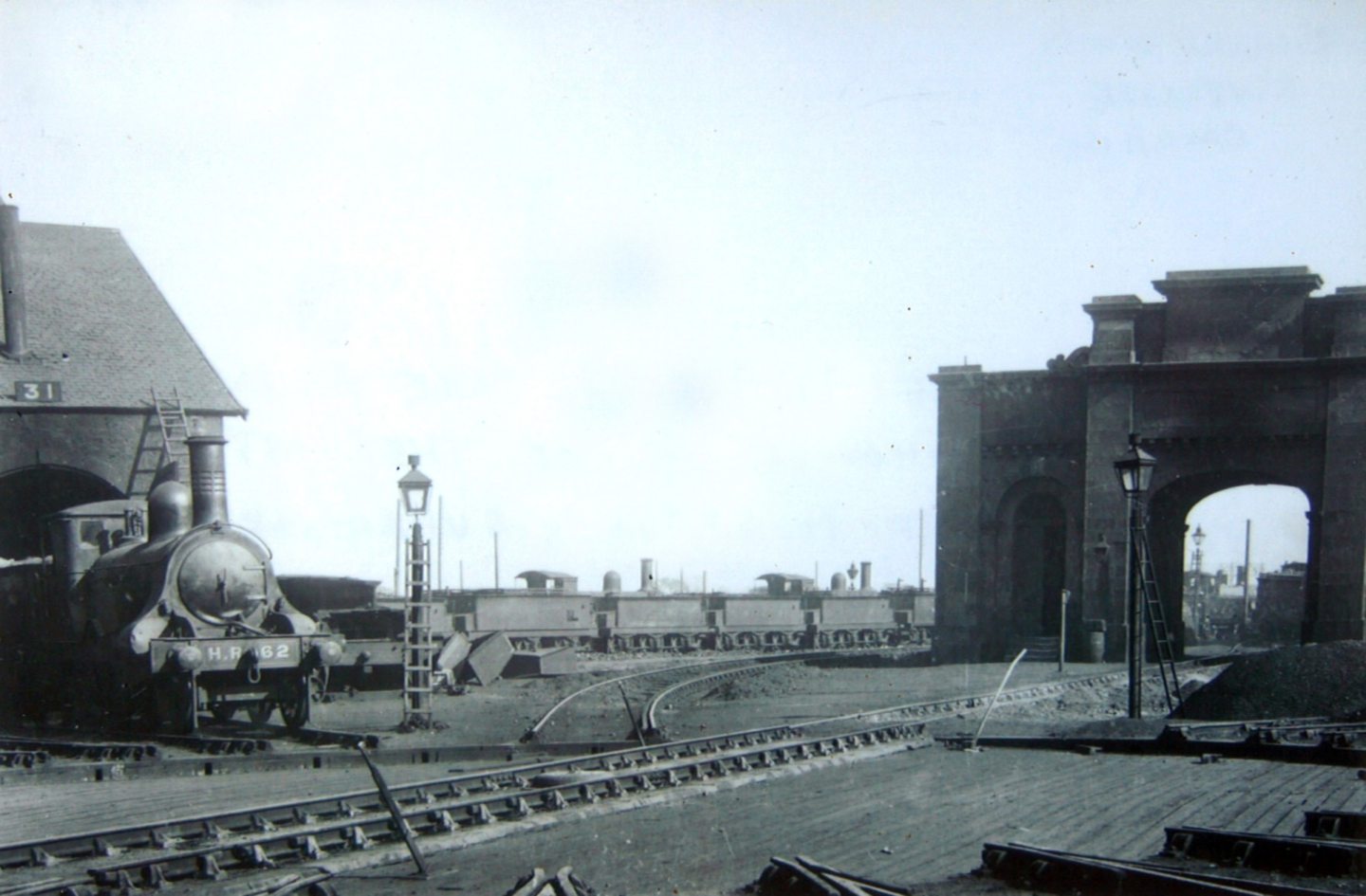

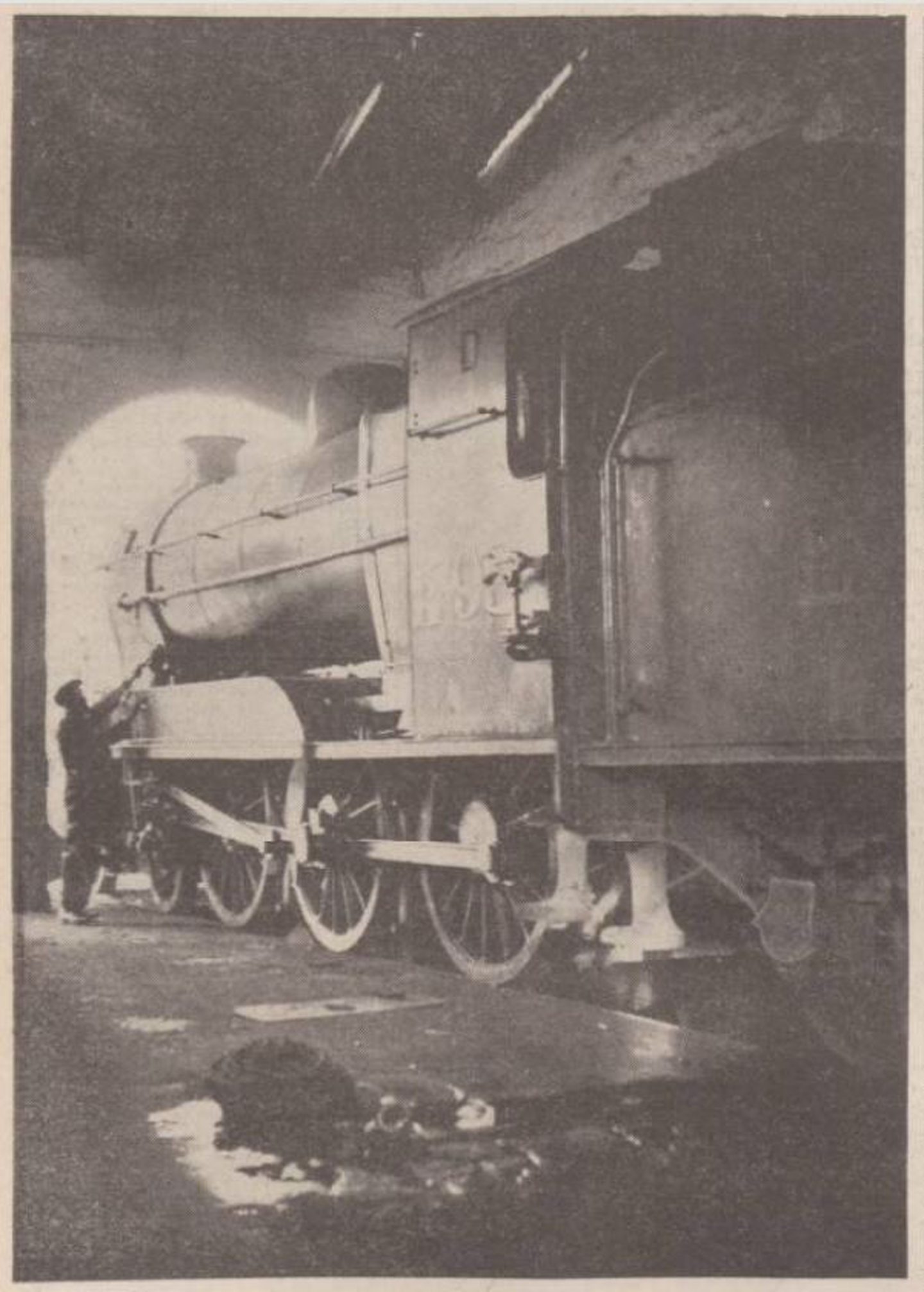

The round-house was built in 1863 around the turntable, creating a semi-circular shed entered via a triumphal arch, known as the Marble Arch.

Not only an attractive flourish, the arch concealed a water tower for the steam engines.

Inverness had the only round-house station in the northern division and it was extended in 1875 creating a C-shaped shed.

Engines accessed their stalls via the large turntable, which was later replaced in 1926 with a 19.29 metre, vacuum-powered turntable to cope with larger and heavier 130-tonne engines.

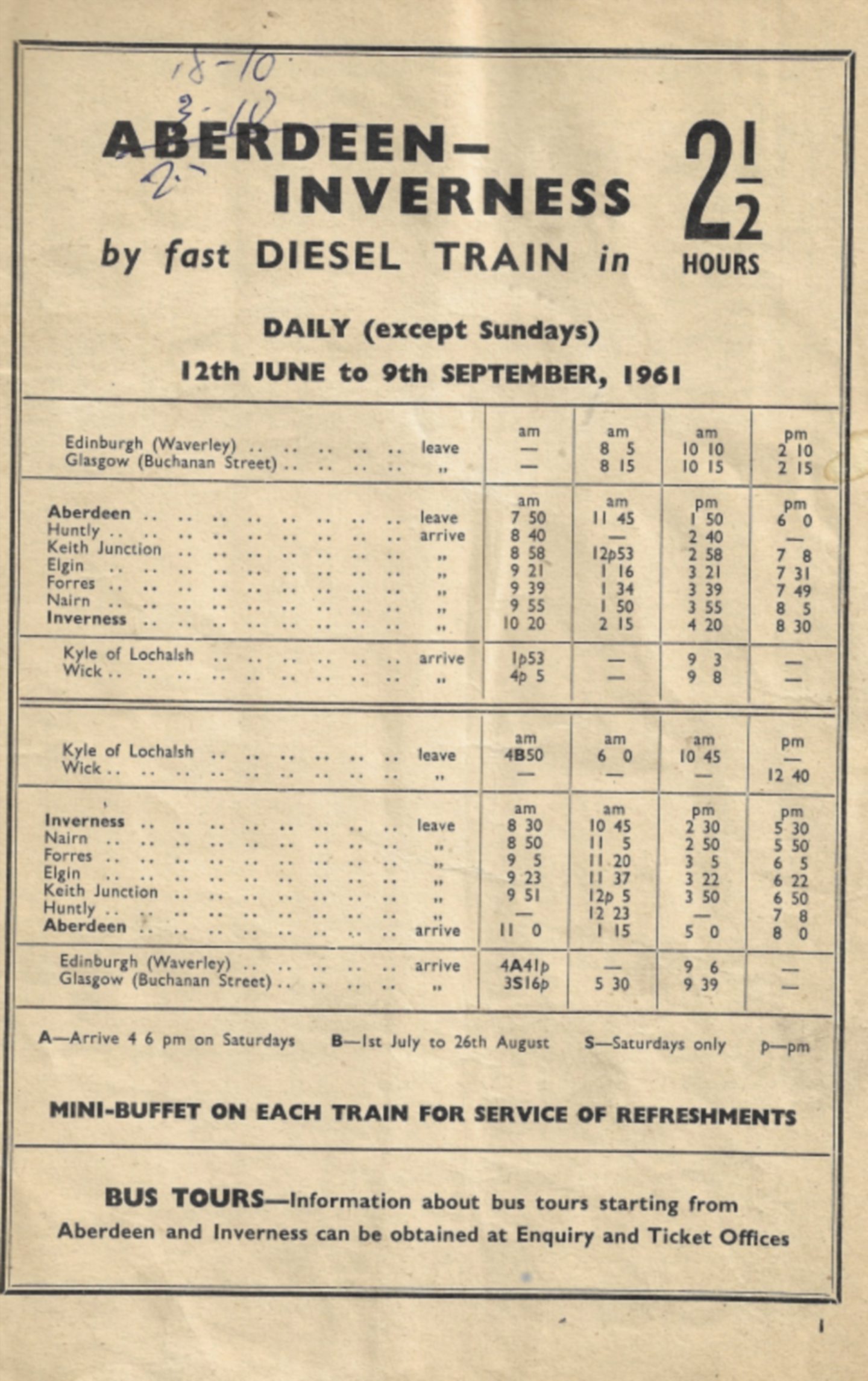

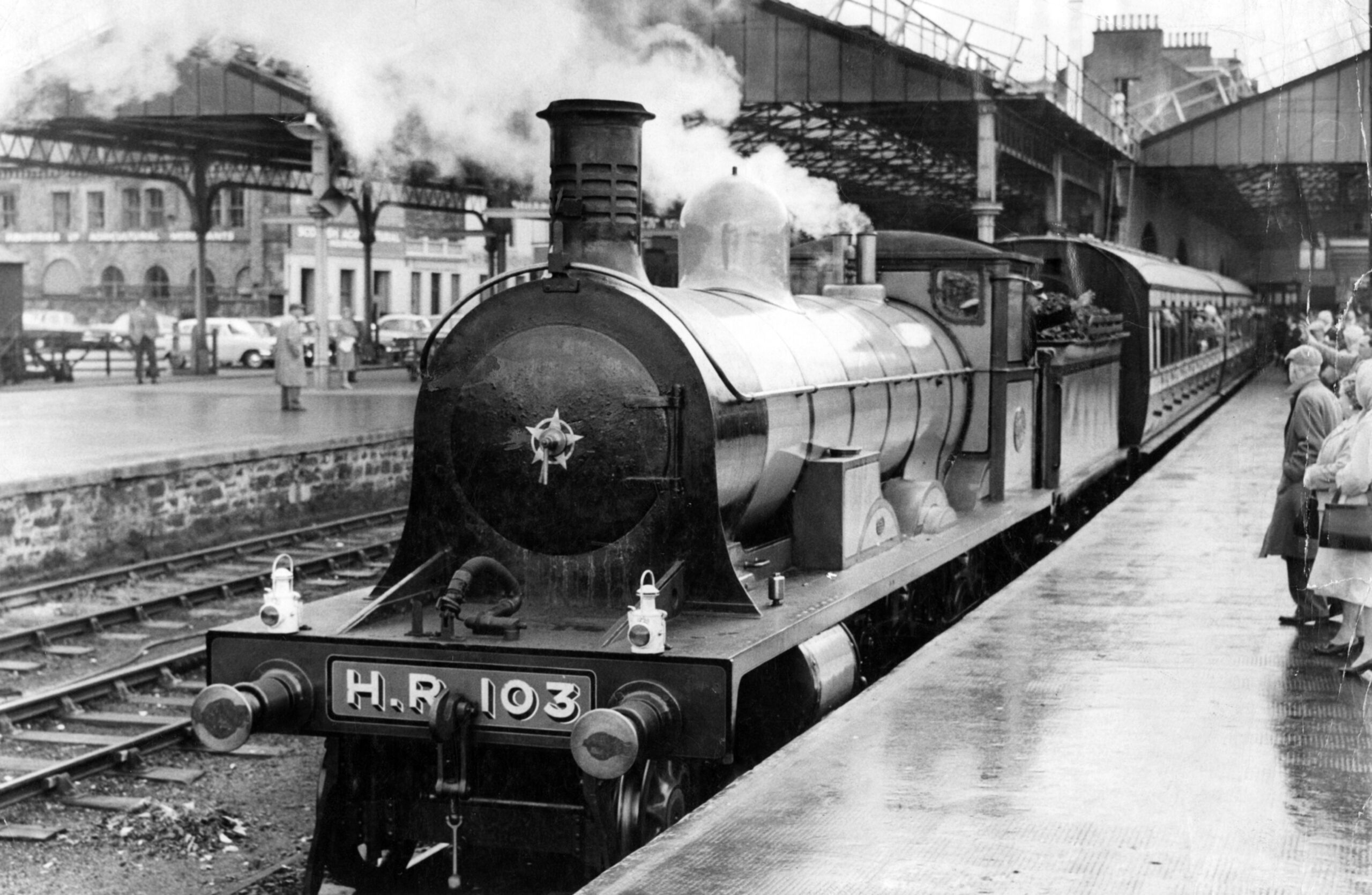

But by the 1950s, steam was beginning to be phased out in favour of diesel.

Victorian engine shed was under threat by 1961

British Railways was keen to reduce the use of steam in the Highlands due to the cost of hauling coal to depots.

Diesel locos also had the advantage of being able to be driven from either end and did not need turntables.

John Baxter was estate surveyor for the Scottish region of British Railways in 1961.

He gave evidence at an inquiry ordered by the the Secretary of State for Scotland into Inverness Town Council’s development plan.

The council wanted to widen Millburn Road and demolish historic shops and buildings at Eastgate.

It would also see many railway buildings and sidings removed to enable livestock markets to stay on Millburn Road rather than moving to the Longman.

1963 saw demolition of round-house and turntable filled in

Mr Baxter told the inquiry there would be changes in railway property in the centre of Inverness “on account of dieselisation, the modernisation of the railways and the rationalisation scheme for the railways”.

When asked if the round-house engine shed would become redundant, he replied: “That is anticipated.”

And within two years, the inventive and impressive round-house – a true triumph of Victorian railway architecture – was gone.

The turntable was dismantled and removed, and the pit was infilled with the tools once used to repair steam engines, as well as rubble from the round-house demolition.

For another 20 years or so, the site was occupied by an extension to the cattle mart – the days of steam locomotives long gone.

The mart also closed in the 1980s, but it was only when the site was redeveloped for building Safeway in 1999 that the turntable was rediscovered.

The ghost of Inverness’ railway past

It was unearthed during an archaeological examination before the carpark was built.

Some Invernessians might even remember windows were created in the hoardings along Millburn Road so people could glimpse the railway relic before it was covered up once again.

But although it is gone, this time it’s not forgotten – the turntable was carefully filled in and preserved beneath the surface.

And if you look closely in Morrisons’ car park you’ll see a little sign explaining the site’s significant history.

Granite setts salvaged from the demolition of the mart were also laid out in the car park marking out the vast circumference of the old turntable.

A ghost of the steam age, it’s a subtle reminder of Inverness’ rich railway heritage.

ALL IMAGES IN THIS ARTICLE ARE COPYRIGHT OF DC THOMSON AND THOSE WHO SUBMITTED PHOTOGRAPHS. UNAUTHORISED REPRODUCTION IS NOT PERMITTED.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation