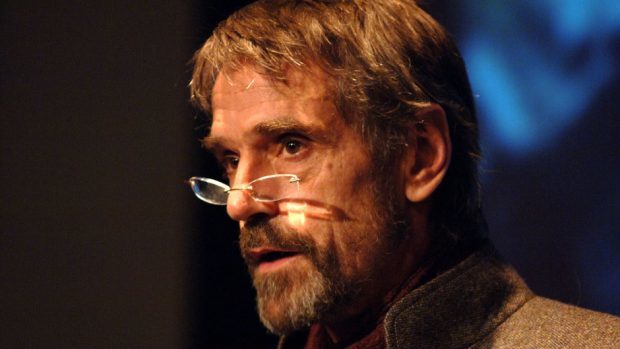

At 67, and with over 45 years in the industry, Oscar-winner Jeremy Irons has paid his dues.

“I don’t want to work very much any more. I’ve done most things and I don’t really need to work,” states the fantastically-dressed actor.

“No longer do I have that great ambition of, ‘I want to be great, I want to succeed’, that I had in my 30s and 40s.”

But for he who maintains “I like to spend more time NOT working”, 2016 is a contradiction of sorts.

Not only has the veteran actor recently opened Eugene O’Neill’s Pulitzer prize-winning masterpiece A Long Day’s Journey Into Night at the Bristol Old Vic to critical acclaim, he can also be spotted on the big-screen – both in Ben Wheatley’s adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise (alongside man-of-the-moment Tom Hiddleston) and in Batman v Superman: Dawn Of Justice (Irons’ first blockbuster in 20 years).

Yet, perhaps most telling of his versatility is his stint as eminent professor G.H. Hardy in maths biopic The Man Who Knew Infinity.

“What excited me was that I knew nothing about the story, nor the man, and I found the mathematics of it all fascinating,” declares Irons, whose top credits include Dead Ringers and Reversal Of Fortune.

“Another attraction was that I’d be playing a typically closed-off boarding school-educated Englishman, who for professional reasons, pulls an uneducated Indian mathematician from a life full of colour, warmth and emotion, and brings him to a rather cold country on the brink of war.”

Directed by Matt Brown, and based on the 1991 book of the same name by Robert Kanigel, The Man Who Knew Infinity tells the improbable true story of Srinavasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel, of Slumdog Millionaire), a 25-year-old self-taught genius who, determined to pursue his passion, writes a letter to G.H. Hardy (Irons) at Trinity College, Cambridge.

After recognising the originality and brilliance of Ramanujan’s raw talent, and despite the scepticism of his colleagues, Hardy invites him to travel from Colonial India to Cambridge in 1913, so that his theories can be explored.

To prep for the role, Irons admits he read the book for the first time – “If you’re doing a movie and a book exists, you always read it just to fill in the gaps, because a movie can’t possibly cover everything that a book covers” – as well as sourcing photos of Hardy and a number of the academic’s writings.

But the Isle of Wight-born star believes his best work happens when he’s simply “having fun”.

“I used to be a perfectionist; I’d try to get things absolutely right and I was a pain in the arse. You can’t make everything…” he tails off. “Look, you try and try and try, but then you see the film and it’s ghastly and you think, ‘Why did I bother’?

“You know what it’s like in the office: if everybody is easy together, then ideas flick up and it’s great. If everything is ‘urghhh’, somehow everything closes up inside because you’re nervous and you don’t want to step on people’s toes.

“That’s what I love doing in life: making things easy, so that everything is a bit of a party.”

It’s a philosophy he hopes he will brush off on his actor son, The Riot Club’s Max Irons.

“There’s a lot of rejection in this business and I worry, as you do for your children. But he seems to be happy; he seems to be much liked,” says Irons, who has two children with wife of 38 years, actress Sinead Cusack.

“I don’t have to teach him anything. He’s my son, so he is a perfectionist. But what I am trying to do, if anything, is gently tell him to enjoy the party.”

For Irons, revelry comes with enjoying life – and specifically, finding peace.

“I find it in my garden, with my dog, on my motorbike, when I’m sailing. I tend to do these things alone quite a lot.

“You get to my age and you begin to think there aren’t going to be that many more summers, so I’d better make the most of this. And I better make the most of these friends because friends are dying. It’s terrible.”

Not one to hold his tongue, Irons’ no-holds-barred opinions have often got him into trouble, from slips on gay marriage to his most recent backlash over abortion comments (“I believe women should be allowed to make the decision, but I also think the church is right to say it’s a sin”).

On his likeness to Hardy, he begins: “I’m not an atheist, but I think if I had a chance to help anybody… I would like to feel that in some tiny way, the world is a slightly better place because of my passing through it. That’s not to be grandiose: I don’t wake up in the morning thinking, ‘What can I do today to make the world a better place’? But I care about the world, people and happiness, so in that way, maybe I share a world view with Hardy.”

Though unlike Hardy, he is an open book when it comes to religion.

“I go to my local church in Ireland, which is Catholic, but I’m not a Catholic. It’s a wonderful centre of the community. I believe in Jesus’ teachings, I believe in Buddha’s teachings, I believe in a lot of Muhammad’s teachings; I think they were all searching towards the centre of human nature.

“But the church has lost touch with modern life, and although I think it’s great we have an organisation that puts the brakes upon this relentless change we live under, organised religion is not my bag. Organised anything is not my bag.

“I have an anarchic nature and I believe we should make our own rules,” Irons confesses. “I have a phrase in my diary that says: ‘To live outside the law, you must be an honourable man’.”

The Man Who Knew Infinity is in cinemas now.