Cinemagoers across the country will queue up this weekend to watch Christopher Nolan’s big-budget take on the Battle of Dunkirk.

But the real-life tales of heroism from those on the ground are enough to rival any Hollywood blockbuster.

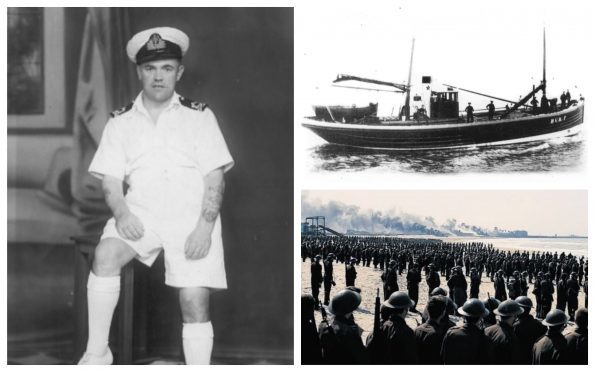

One of the most remarkable stories belongs to Peterhead skipper Rory McLean, who faced off against the Luftwaffe in a deadly firefight after saving more than 700 men.

Skipper McLean, one of five brothers from a long-line of north-east fisherfolk, took the helm of the Nautilus – one of many vessels requisitioned by the UK Government during the war – after a lifetime working on Blue Toon trawlers.

Speaking to The Press and Journal this week, his nephew Jackie McLean, 78, revealed how the skipper’s actions had become the stuff of legend in their family after being passed down through the generations.

He had been laying dans for mine-sweepers off the coast of Dover when the first panicked call came in. Any available vessel was to immediately sail in the direction of France as the military began evacuating allied troops surrounded by German forces.

McLean immediately dropped the buoys and diverted his ship towards the battleground – in what would ultimately be her last voyage.

Some way across the English Channel, the former-fisherman heard screams coming from the waves. Around ten men had been stranded in the water, left clutching on to wreckage for their lives.

The skipper pulled them aboard and then, survivors and all, continued on to Dunkirk. He handed them over to the cruiser Calcutta when he arrived in northern France and then set about evacuating more troops from the beach.

Using a lifeboat commandeered from a cargo-vessel, McLean began ferrying soldiers from the surf back to his ship and then out to a destroyer lying further offshore.

Carrying 40 men at a time, it was only after around 700 had been saved that tragedy finally struck McLean’s ship. Peering out through the windows of his wheelhouse, the skipper saw 14 German Stukas dive-bombing towards him.

The bombardment that followed proved too much for the Nautilus. In the burst of bullets and bombs, nine crew members were injured but incredibly everyone on board survived.

McLean urged them up a rope and onto the nearby Greyhound destroyer while he got behind a Lewis machine gun on the stricken vessel. He shot back as his cargo of soldiers climbed one-by-one to safety.

Moments later he was back below deck, burning his confidential papers when he heard a shout. A man had fallen in. Almost immediately, McLean dived in after him and pulled him to safety.

As he would later discover, the final soul he saved that day belonged to one of a number of soldiers from the north-east who now owed their lives to the skipper.

McLean’s nephew, himself a retired shipbuilder from Peterhead said: “As it happens, the man he saved was from Cullen. We think his name was Mr Mustard.

“He fell in and my uncle shouted that he was in the water and then he dived in to save him. I don’t know how he had the courage to do it. I know for sure that he saved at least two men from the north-east but there may have been be many more.”

While the Nautilus, sunk at the bottom of an unfamiliar shore, never made its way back to its home port of Findochty, McLean did return to Peterhead and his life as a fishermen. He later retired in the town but according to his nephew, rarely spoke of his experiences.

“I knew him all my life but he didn’t speak about it much,” he said. “We are all very proud of him and what he did. My father and my auntie used to tell us stories about him being a hero at Dunkirk. To save all those lives is incredible.”

An enduring myth about the evacuation is that civilian fleets were forced to step in after the Air Force simply failed to protect soldiers on the ground.

However, nearly 80 years after McLean first arrived on the coastline in northern France, the raising of an official secrets gag has revealed the RAF actually played a major role in saving lives on the beach.

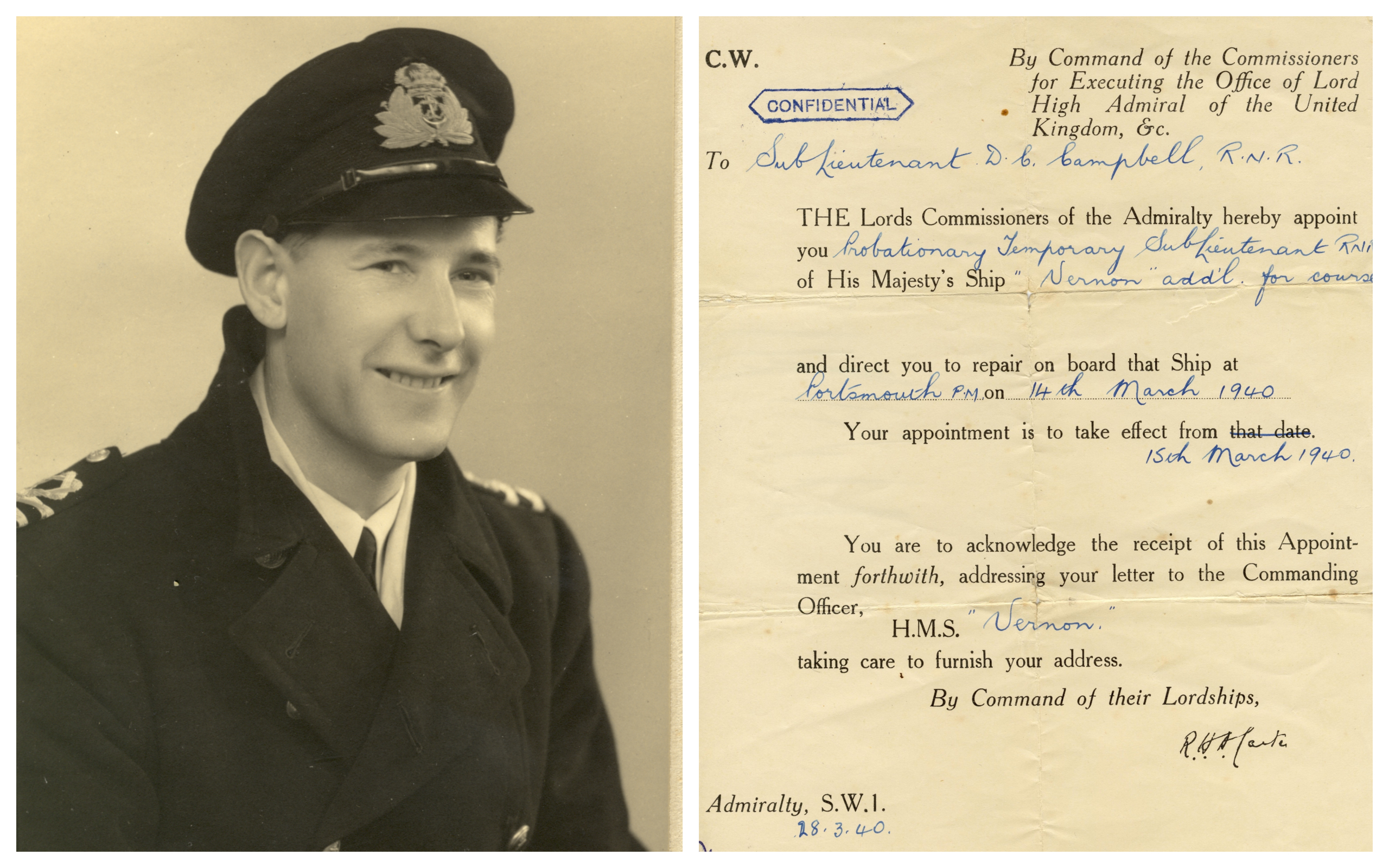

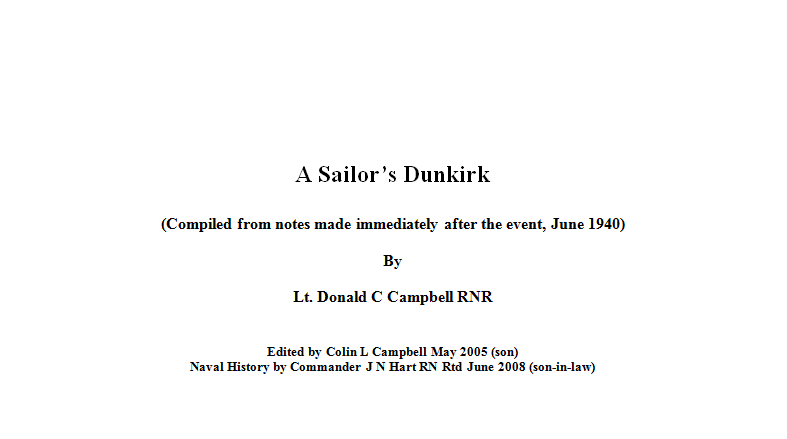

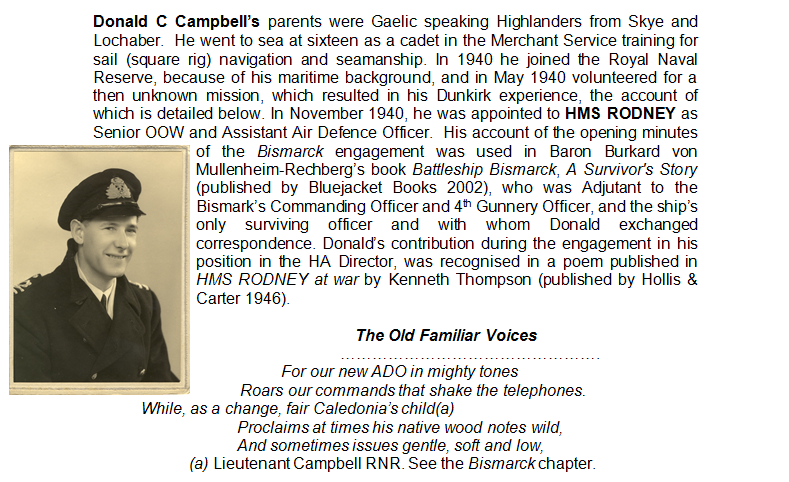

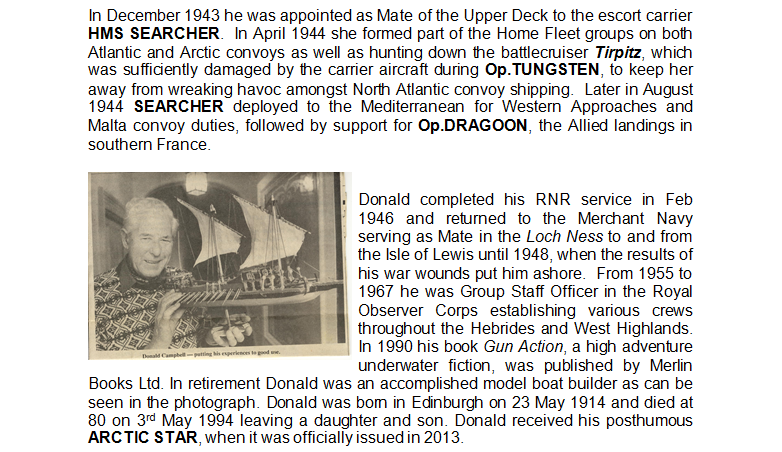

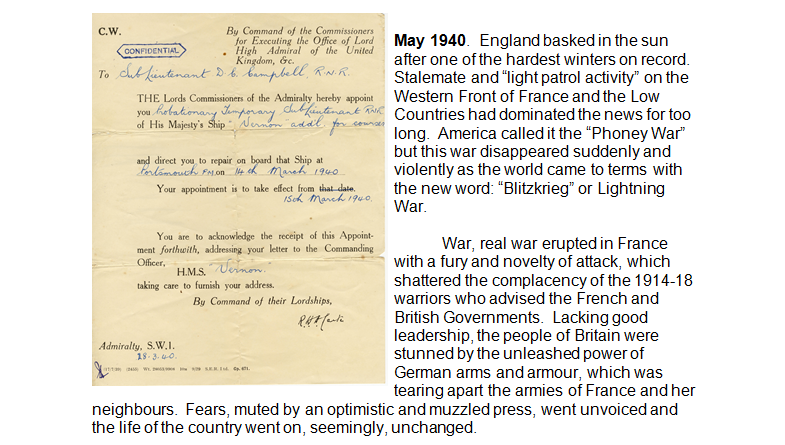

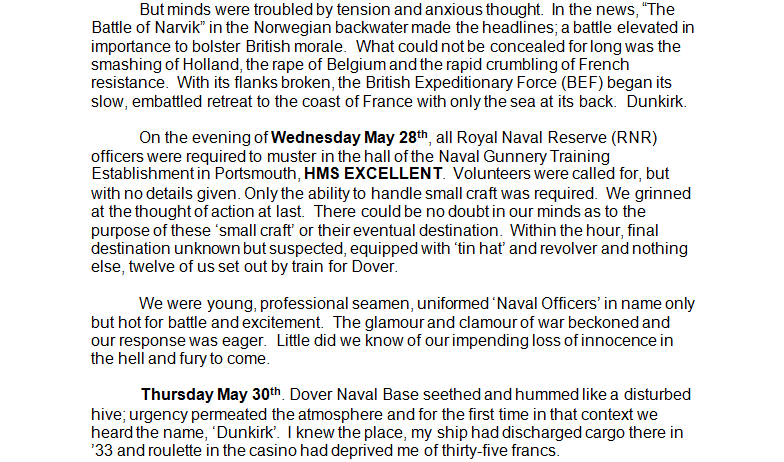

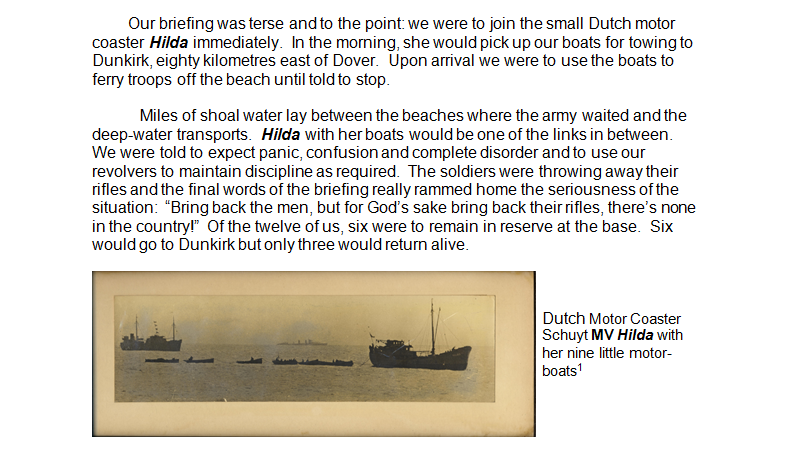

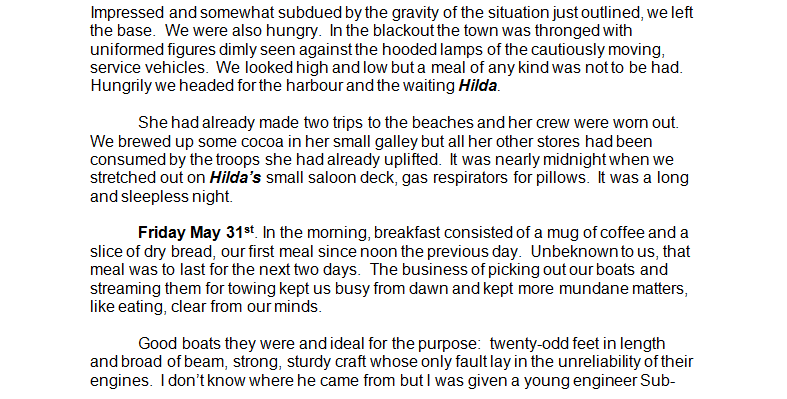

One Lochaber seaman there that day, Lt Donald Campbell, wrote at length about his experiences at Dunkirk and his own “loss of innocence in the hell and fury” of battle.

His memoirs, published in full today for the first time on the Press and Journal website, reveal how aircraft “patterned the sky”, leaving vast oily cloud encroaching overhead.

He wrote: “Later, when this hell subsided, returning soldiers beat up RAF personnel on sight, blaming them for what they had gone through, as they thought, without air support.

“The air force was there. Twos and threes, gallant in their pitiful few in the face of the Luftwaffe air fleets comprising twenty or thirty units; attacking again and again and not always in vain. Not all those parachuting men were German.”

Lt Campbell’s first-person account provides an important documentation of one of the most important events in British Army history but it also serves as a striking insight into the ordeal endured by those on the ground.

In one particularly striking passage, he writes: “Never will I forget the courage, self-discipline and patience of these exhausted, shell-shocked men. I gazed along the beach at the smoking rubble, abandoned transport and discarded equipment; interspersed with the towering bomb bursts and the still figures sprawled in the sand.

“These men had been marching and fighting for a week or more; with little food and less sleep, inadequately armed and on the move the whole time under unrelenting attack from the air; morale should have been non-existent. Their sense of betrayal, lack of direction or purpose must have been soul destroying.

“But they could still laugh, crack a joke and help the wounded, who were always lifted in first into the waiting boats. Few were without packs; none that I could see lacked a rifle or ‘Bren’ gun. I never felt more proud of my countrymen until that moment.”

Lt Campbell’s daughter Alison Hart, speaking at her home in Nairn yesterday, said she knew nothing of her late father’s memoirs until her brother Colin showed her, about 10 years ago. And she regrets not asking her father more about his experiences.

“I knew some of the stories, I knew he’d been at Dunkirk,” she said. “I knew that when he and a friend arrived at Waterloo Station people just started to clap automatically as these two young naval officers walked through – and he was totally taken aback by that.

“He didn’t speak much about Dunkirk. He spoke more about his time on HMS Searcher – and HMS Rodney which was responsible for knocking out the Bismarck.

“He must have been terrified – like all of them – but they were trained and they were doing a job.”

Mrs Hart said her mother Joan, who served on HMS Orlando with the Women’s Royal Navy Service, told her how he regularly woke up screaming in the wake of Dunkirk.

“I think, like a lot of these men, they didn’t really talk about it,” she said.

Ruth Duncan, curator of the Gordon Highlanders museum in Aberdeen, believes the evacuations had a lasting impact on families across the north.

She said: “It must have been quite an experience for those involved. They will have been subject to enemy shelling, exposed and out in the open after presumably marching for days at a time. They must have been exhausted.

“For families back home, Dunkirk will have had a huge impact. I imagine for those who were safely evacuated it would’ve been a story of happiness for the families, but a lot of it would’ve involved not knowing and waiting to hear news.

“And for some people it probably would’ve been months or weeks before they heard whether they had made it across or whether they were missing or captured.

“You don’t have to go too far back through family trees to find connections to St Valery or Dunkirk or even the Gordon Highlanders.

“There are members of everyone’s families across Aberdeen, the north-east and beyond who have connections to this historic moment.”

In May, the cash-strapped museum, which documents the 200-year history of the famous Gordon Highlanders regiment, launched an appeal for funds after being told it could face closure.

The award-winning facility has seen dwindling returns from north-east businesses in light of the oil price downturn and organisers now need to raise around £300,000 over the next three years to secure its short-term future.

The museum, re-opened in 2006 after a £1.2million refurbishment, saw around a third of the overall target reached just weeks after launching the official campaign.

For more information, visit www.gordonhighlanders.com