Aberdeen’s influence on the events leading up to and the creation of the National Health Service in 1948 was extraordinary.

It’s not quite enough to rename it the North-east Health Service, but that’s not far off it.

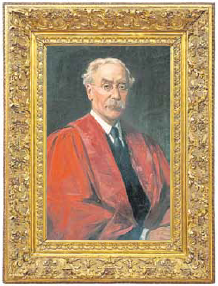

This story remains little known but it begins with Matthew Hay, professor of forensic medicine and public health at Aberdeen University, and also the city’s medical officer of health.

His vision led the way in Europe to creating a new medical campus bringing all services, teaching and research, together on one site.

Prof Hay, who died in 1932, lived long enough to see construction start and by 1939 Foresterhill already had a new infirmary, children’s and maternity hospitals and a medical school.

Prof Hay also had a wider national outlook as a member of the General Medical Council and the Medical Research Council.

In 1916 he wrote: “A single communal or state health and medical service would give the best results for the health of the community.”

The following year he organised the first confidential inquiry into maternal deaths to learn from tragedies and reduce risk of them happening again. This innovation was later to be copied around the world.

Hay also inspired generations of his students such as Leslie Mackenzie. Together, in 1902, they served on a royal commission looking into the health of children which led to the introduction of school medical inspections.

Mackenzie and his wife Helen were also friends of Beatrice and Sidney Webb, social reformers and founders of the Fabian Society.

He was also the key medical figure in the Highlands and Islands Medical Service, a forerunner of the NHS which was set up in 1913 to provide affordable medical and nursing care to people in the crofting counties.

State funding was used to give practical help to doctors and nurses. Unlike the NHS, it wasn’t free and didn’t have its own administration, but it did figure as a model for the planning of the new national health service.

The Highlands also provided inspiration for the novel and film that helped to shape public attitudes against the existing health system.

Writer AJ Cronin was the JK Rowling of his era. Hollywood fell over itself to turn his novels into cinematic blockbusters. He had worked in Nye Bevan’s home town, Tredegar.

But being diagnosed with a duodenal ulcer triggered his career switch from medicine to writing. He moved with his doctor wife Agnes and their young sons to a rented farm cottage at Dalchenna, near Inverary. Money was tight and prospects bleak, but his second novel, The Citadel, in 1937, broke all records in America for publisher Little Brown and for an all-star movie. The film’s impact was sufficient to merit a re-release in 1948.

Aberdeen’s other major influence was work by John Boyd Orr at the Rowett Research Institute. His 1936 report Food, Health and Income revealed the shocking truth that at least one third of the UK population were so poor they could not afford to buy sufficient food to provide a healthy diet.

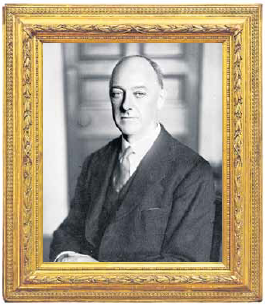

By 1938, there was also something of a novelty – a UK health minister who knew what he was talking about. Walter Elliot and Boyd Orr were pals from their medical undergraduate days in Glasgow.

Elliot continued his postgraduate studies in nutrition at the Rowett during his summer holidays away from politics.

Elliot was able to apply this knowledge in his ministerial career, first in Scotland providing free or cheap milk for school children.

The advent of war triggered the practical application of the Rowett’s research, with food rationing advice that ensured everyone at least had the basics.

Elliot’s successor as minister was Nairn-born Michael MacDonald, (son of the former prime minister Ramsay). He was responsible for a critical appointment, Sir Wilson Jameson as chief medical officer (CMO).

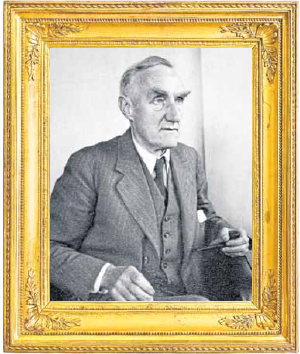

Jameson had previously compared the health department in Whitehall unfavourably to a chaotic girls’ school.

But he took the post out of a sense of duty and he went through the place like a dose of salts. His career to date had been in public health, latterly as dean of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, founded in 1899 by another Aberdeen graduate, Sir Patrick Manson.

Jameson also believed public health worked better with the public’s involvement.

He instituted monthly press briefings during which he answered journalists’ questions. In 1941, he became the first civil servant to broadcast on the BBC, when he promoted diphtheria vaccination, following this up in 1942 with a broadcast on the taboo subject of venereal disease.

His soothing Aberdonian accent and calm delivery was a winning combination.

Then came Bevan in July 1945, with a pledge to launch a National Health Service within three years.

This would have been an ambitious timescale even if Bevan had not promptly binned an existing plan for a health service drawn up by his coalition government predecessor Henry Willink; an action that was to the consternation of his new permanent secretary Sir William Douglas.

Former miner Bevan had little in common with the older Scots, Jameson and Douglas.

However, they overcame initial suspicions to develop an extraordinary bond of mutual trust. It was this, above all, that actually delivered the NHS in July 1948.

They faced an enormous administrative challenge and preparing for an avalanche of unmet needs, such as for free hearing aids. They took the best model available and mass produced it as the Medresco – named after the Medical Research Council which carried out the assessment.

Douglas brought wide experience in the Labour Ministry, Treasury and the Scottish Office as secretary to the health department.

Jameson had impeccable credentials as CMO for more than 30 years working in London. He could float ideas not yet formulated as policy. As relationships with the British Medical Association (BMA) deteriorated, he still held its confidence – in his early career he had set up the BMA’s division in Finchley.

Aside from the day job, Jameson also played a leading role in establishing the World Health Organisation (WHO) attending meetings in Paris, New York and leading the UK delegation at the first WHO assembly in Geneva, a month before the NHS launched.

Jameson, Hay and Mackenzie were modest about their own achievements.

The Press and Journal reported Jameson’s final press conference on his retiral as CMO in May 1950 where he described himself as “an average boy” from Aberdeen Grammar School and Aberdeen University and a pretty poor golfer.

However, in a speech to Parliament in 1958 to mark the 10th anniversary of the NHS, Bevan took the unprecedented step of breaking the code of civil service anonymity to name both Jameson and Douglas.

Bevan praised the team effort of his civil servants to help create the NHS but singled out Douglas and Jameson for their individual efforts.

“The nation was extremely fortunate in having two eminent civil servants of that calibre at the ministry at that time. I am quite certain that if honourable members and the nation generally knew how much work they did and what a huge task it was, they would feel very grateful indeed,” he said.

In other words… without them, it wouldn’t have happened; at least on time and in the form it took.

Chris Holme is a former Aberdeen Journals reporter and Reuters Foundation fellow in medical journalism.