Scientists from St Andrews University believe they could have solved the long-standing mystery of why our planet is so wet.

An international team of researchers, working in partnership with the Scottish institution, have now discovered that tiny grains of dust, no larger than the head of a pin, can accumulate substantial volumes of water from surrounding gases and ice.

They have reasoned that these minuscule motes and their accumulated water could collide, stick together and form a planet like Earth with enough water to fill its oceans.

The university researchers, alongside colleagues from Germany and the Netherlands, concluded that the process could take just one million years – which is enough time, according to commonly accepted cosmological evolution scenarios – for the formation of stars and planets.

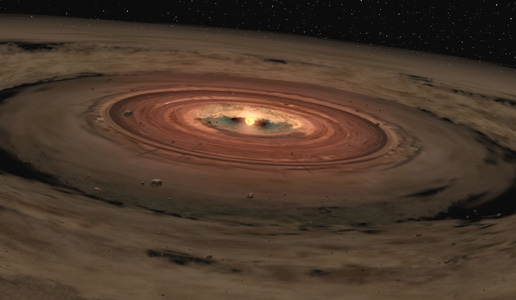

They believe the water-rich dust could clump together to create the very first pebbles, followed by kilometre-sized boulders and eventually, entire planets.

Their research was published recently in the scientific journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

The question of why liquid water is so relevant on our planet, especially compared to other heavenly bodies in our local solar system, has long inspired scientists across the globe.

Other hypotheses which have been put forward to explain the origin of Earth’s oceans, seas and rivers include transferral of water from comets and asteroids.

Peter Woitke, of the Centre of Exoplanet Science at St Andrews University said: “The mystery as to why Earth has so much water has previously baffled researchers.

“One theory suggested that the water was delivered by icy comets and asteroids that hit the Earth.

“A second scenario suggests the Earth was born wet, with water already present inside ten-kilometre (6.2 mile) boulders from which the planet was built.

“However, the amount of water that these large boulders can contain is disputed.”