One wouldn’t normally associate military men with being skilled in the art of embroidery.

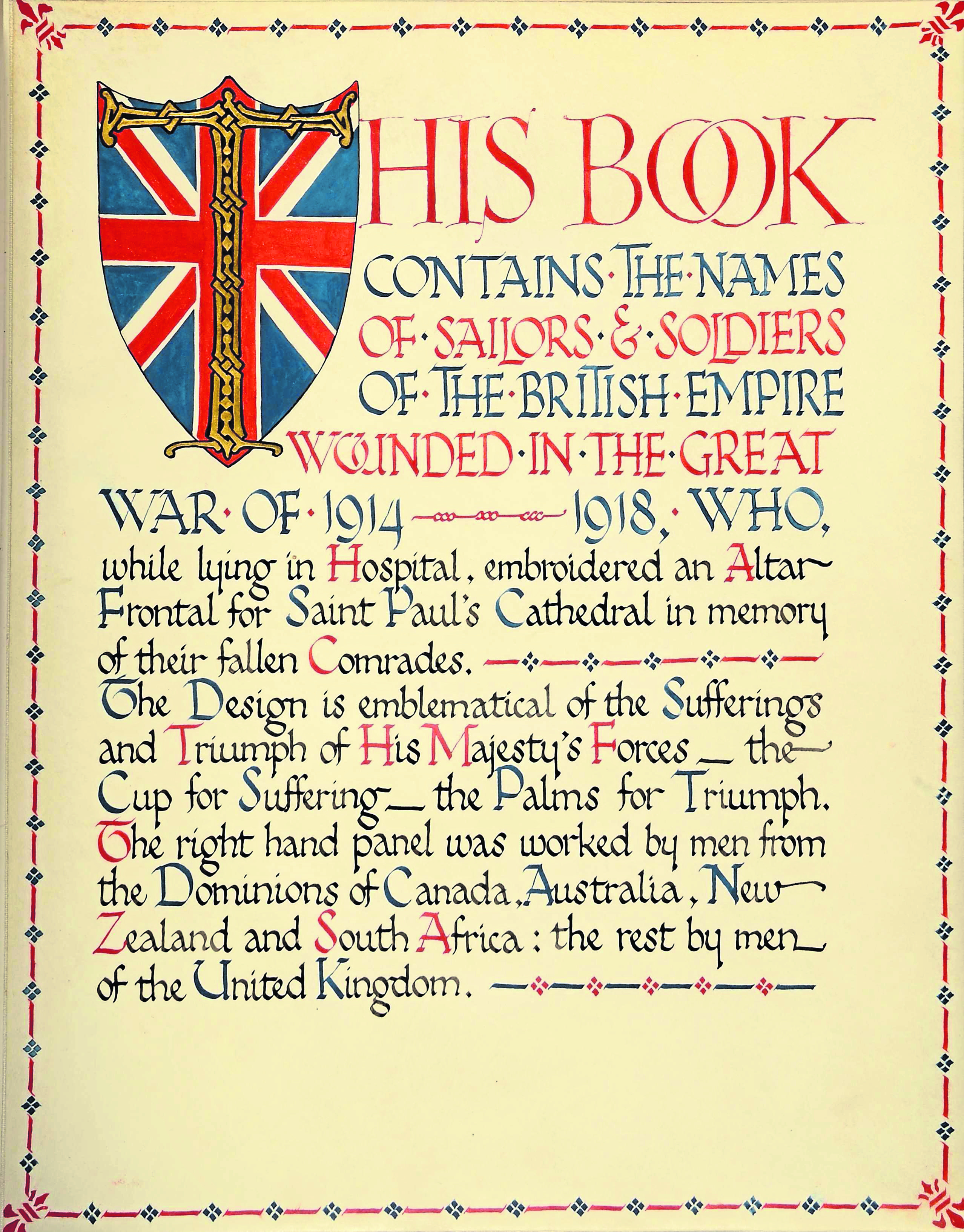

But an intricate and beautiful altar frontal, which graced the centenary commemorations of the First World War at St Paul’s Cathedral last month, was partially created by soldiers from a north-east auxiliary hospital.

Investigations are continuing into the history of Durris Kirkton Hall, which was used for medical purposes during the conflict.

The work, which has been carried out by Jane Robinson – a volunteer researcher at St Paul’s – has also highlighted how two of the wounded troops came face-to-face with world-renowned entertainer Sir Harry Lauder.

Ms Robinson has unearthed a variety of newspaper cuttings and archive photographs from the war and joined forces with Lorraine Stewart of Kincardineshire Ancestors to pursue her quest.

They testify to how the hospital looked after up to 15 or 20 soldiers at a time between 1914 and 1919, four of whom were among the 138 men who created the stunning altar frontal.

Mrs Robb, chairwoman of the Durris Kirkton Hall management committee said yesterday: “Jane got in touch with us after discovering the link to the embroidery and things have moved on since there.

“She provided us with a lot of information about how the community hall had been used as a hospital and it has given us a remarkable and poignant connection with the past.

“There are parts of the current site which haven’t changed in the last 100 years and the old clock still resides in the Hall.

“The horrors of the First World War saw countless lives lost across Europe, as well as many men returning home severely injured, physically and mentally.

“Hospitals around the UK took in the men from all the allied countries as they recovered and recuperated.

“Of all the many forms of rehabilitation, embroidery was seen as a good way of reducing the effects of shell shock, owing to its intricacy and need for concentration and a steady hand.

“It has been fascinating to find out how the troops who were based at the auxiliary hospital in Durris contributed to this wonderful centrepiece.

“Melissa Coutts, our secretary and myself went down to St Paul’s Cathedral last month on Remembrance Sunday to attend the World War One Altar Frontal remembrance service and it was a very emotional experience.”

The Durris Estate, on the Dee, was originally a Clan Fraser estate, but was purchased in 1834 by Andrew Mactier, a successful Madras merchant, who created a 200-acre arboretum around the house.

A later owner, James Young, invented paraffin, which is why the local people often call Durris ‘Paraffin House’. He expanded the forest by adding rare trees from the Far East.

Mrs Robb added: “We’ve found out quite a lot about the men who were tended to by local volunteers during the war.

“And it has emerged that two of them went for a walk around the grounds of the hospital and came across this fellow who was fishing in the Dee.

“It was Harry Lauder, the man famous for lifting the morale of the troops with such songs as “The End of the Road” and “I Love a Lassie”.

The singer, described by Winston Churchill as “Scotland’s greatest ambassador” raised vast amounts of money for the war effort during the hostilities, for which he was knighted in 1919.

Who were the men who helped create the embroidery?

The four men who helped create the stunning embroidery for the altar frontal at Durris Auxiliary Hospital have been listed as Sergeant Armstrong of the Coldstream Guards, Cadet K Baird of the Officer Training Corps, Gunner Steele of H Battalion and Pte Harris of the 8th Royal West Kent regiment.

Not much information is known about most of these soldiers, but Mr Baird was educated at Heatherdown Prep School and Eton.

On leaving the latter, he relocated to London to train as a barrister at the Inns of Court School of Law, from which he joined the OTC.

Deployed to the front, he was wounded and brought back to hospital in the UK, firstly to Aberdeen and then, for his recuperation, to Durris Auxiliary Hospital in Kirkton.

The London Gazette suggests he was subsequently seconded to the Seaforth Highlanders as a temporary 2nd Lieutenant as part of his demobilisation from the Army.

In 1924, he married his wife, Ernestine, and they and their daughter later moved to start a new life in Africa, making the occasional trip back to London and Scotland.

Mr Baird died in 1968.