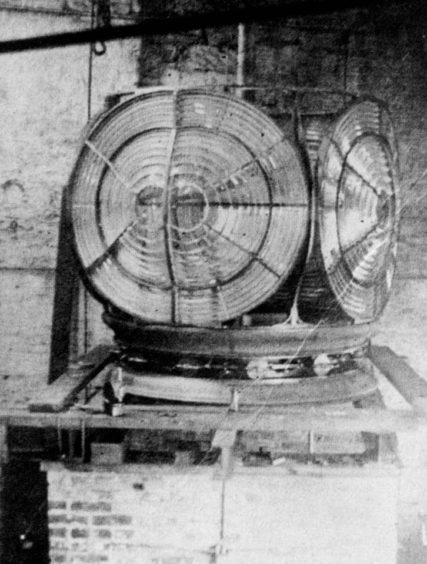

A priceless artefact has arrived at a north-east museum – the oldest Scottish hyper-radial lighthouse lens.

The eight large semi-circle shaped sections of the Fair Isle north lighthouse lens arrived at the Museum of Scottish Lighthouses in Fraserburgh yesterday morning.

Following months of preparations, the lens – which weighs almost four tonnes in total – has become part of the museum’s world-class collection.

Only nine of Scotland’s lighthouses ever had hyper-radial lenses – a larger lens with a greater focal distance than the kind being used at the time – and only six of those still survive.

Four are now in the Scottish Lighthouse Museum, making it possibly the biggest collection of them in Europe.

Museum manager Lynda McGuigan is thrilled with the latest addition to the collection.

She said: “This is our biggest acquisition in around 20 years, since the museum opened and we’re so excited.

“We had originally travelled to Shetland last year to find out about acquiring a few other things and knew that engineer Brian Johnson had found these lenses and sorted new storage boxes for them.

“After inquiring we were told we could have them as a donation.

“It worth over £1million – we insured it on its travels for £50,000 in case something happened but it truly is priceless and nothing could ever replace it.

“It’s an incredible piece of industrial heritage – two of the pieces were on show for a little while in Shetland but since the automation in 1983 the other parts have been in storage.

“No one has seen it whole since the 1980s so we can’t wait to begin putting it together, always having it on show for visitors to see.”

But getting the lens into the building was a major operation.

Two workers from Gray and Adams brought their forklift and donated their time to get it in, as did a local volunteer Grant Duthie who regularly visits the site.

Each section was lifted from its travel crate using the forklift and strops, lowered onto a pallet, power washed and then lifted by the machine to the museum doors.

Man-power was then used to pull the pallet holding the lens up a ramp to the exhibition room.

After several hours work, the pieces were unloaded and in place.

Ms McGuigan added: “This is such a rare and precious item that we’re delighted it is now part of our worldly significant collection that will draw people to Fraserburgh.”

Bringing the lens to Fraserburgh

The four-tonne lens was carefully packaged and transported from Shetland where it had been stored for more than 35 years.

Scottish Lighthouses Museum collections manager Michael Strachan travelled north to oversee the packing of the eight half-moon shaped glass and brass components.

Each one was then power-washed before being carried into the museum by the forklift. It will be built up in the coming weeks.

History of Fair Isle north lens

The Fair Isle North lighthouse lens was originally put to work in 1892.

After almost a century of lighting the way for approaching ships and warning of the perilous rocky edge in the north of Fair Isle, between Orkney and Shetland, the lens was retired in 1983.

Collections manager Michael Strachan said: “The Fair Isle North lens was installed in 1892.

“It was the earliest hyper-radial lighthouse lens in Scotland, meaning it’s the oldest.

“Both the lighthouse and the lens would have been designed by David Allan Stevenson and his brother Charles Stevenson – relations of the famous Robert Louis Stevenson.

“Once in operation, one of the best stories of the Fair Isle lighthouses was during World War 2 when the island was bombed.

“There was a lot of snow and many people were killed in the south due to the bombings.

“Lightkeeper Roderick Macaulay then walked three miles from the north lighthouse, where he had survived an earlier raid, traipsed through snow and high winds to help restore the south lighthouse.

“He then returned in the dark each night to do his own watch at the north lighthouse.

“He was given a BEM for his services.”

Mr Stachan admitted that although picturesque, the Fair Isle lighthouses were not a popular spot among the keepers.

“At the time the lighthouse was manually operated the population of the island was around 50 people and when the lighthouses were automated the population dropped as the keeper families moved away,” he said.

“I don’t think it was a popular place to be allocated if you had a family as the school was so small at the time but it would have been an interesting place to live.”