Centuries-old documents charting the rise of the north-east’s most prominent industries could soon to be made accessible to the public.

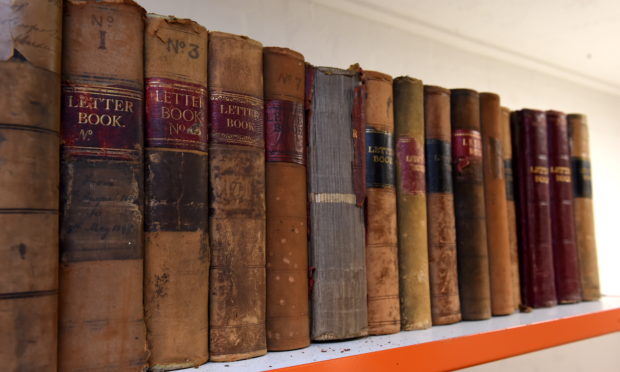

Work is under way to open an artefact centre at the Seven Incorporated Trades of Aberdeen, showcasing a range of books and ledgers which are key to understanding the organisation’s storied history.

The items are currently stored away under lock and key in the facility’s box room, which features walls lined with ornately-decorated safes belonging to each of the sectors represented.

An extensive audit is under way to outline exactly which historic treasures are being kept there and the best way to store them so they remain intact for generations to come.

Ex-deacon Tom Ironside said: “We have set up an artefacts committee and their brief is to look at all the contents then we’ll work to bring the collection up to museum standard.

“We’ve set up an artefact centre at our office on Great Western Road, and that’s where all the old minute books will go.

“Some detail the entire commercial history of Aberdeen, as the trades were so heavily involved in the corporate development of the city.

“Opening this centre is a fairly major step for us.”

The Seven Incorporated Trades has a wide range of historic documentation, paintings and other items stored within its walls, including photo books featuring portraits of previous cohorts of members and minute books which detailed meetings held as far back as the 1500s.

It is thought that the preservation of some of these is of national or even international importance.

The organisation has also acquired a number of Victorian-era tomes from a separate collection of city industries.

Up until 1846 the Seven Incorporated Trades enjoyed exclusive trading privileges, leaving those outside the organisation at a disadvantage.

Mr Ironside said historians can use their collection to understand what running a business was like at the time.

“The main difference between them is that, because Aberdeen was a royal burgh, the new trades were allowed to export but the older ones couldn’t,” he added.

“At one stage there were battles between apprentices of the different groups.

“The amount of research we can do here is brilliant.”

The head of museums and special collections at Aberdeen University, Neil Curtis, said it is “very important” that the Seven Incorporated Trades’ records are properly maintained.

Aberdeen is home to the oldest collection of burgh records in Scotland, with some dating back to the 14th Century.

They have been deemed so crucial to understanding the area’s history that Unesco has listed it among some of the most historically important documents in the world.

Through his role, Mr Curtis has spent countless hours scouring these books and ledgers for facts about the city.

And he said the Seven Incorporated Trades’ collection of artefacts will likely bring even more understanding of the past.

“We have this continuous run of records about the town centre, with the burgh records and now the trades, and we see the same people cropping up.

“William Guild was a principal at Aberdeen University as well as the first patron of the Seven Incorporated Trades, for example.

“So to get that picture of what’s been happening in the city, you really need all of these linking archives to form a full overview.

“These records are really significant.”

Tales of their own

While the documents stored within Trinity Hall are capable of telling countless stories, the building’s furnishings also house tales of their own.

A pair of tables in one of its portrait-lined rooms have been dated back to the 12th Century, with work ongoing to trace their origins even further.

One of the pieces contains a stone with a fossilised fish inside, which was thought to have been used in the construction of William I’s palace in the city.

A professional was able to examine the stone and suggested that it originally came from the island of Oland, off the coast of Sweden, before it was recycled into a piece of furniture.

Mr Ironside said: “William I had a palace on Guild Street, and it is thought he gifted the table to the friars in the city at the time.

“They had it until the reformation when the friary was burned, and this table reportedly came from that.”

He added: “It’s carved on the underside, so we think it has been reused.

“The royal palace was demolished around the same time, so perhaps it came from there.”