If you turn right at the entrance of Aberdeen Maternity Hospital, you’ll inevitably come across excited visitors and proud parents cradling their new additions.

Balloons gently bob down the corridor along with bunches of flowers, and families make their way home together for the very first time.

Although a baby symbolises hope, however, the path to parenthood is not always straightforward.

Some parents give a quick glance as they pass through the doors, and look left to where their journey may have started.

For, alongside the neonatal unit where babies can receive lifesaving care, there is a department doing remarkable work.

It can be difficult for those who have yet to fall pregnant to see and hear the joy of others in such close proximity.

The lucky few, however, have experienced both sides of the building – having originally turned left into Aberdeen Fertility Centre.

The unit has been at the forefront of fertility treatment for more than 30 years, with the first IVF baby born in Aberdeen in 1989.

The university department offers a clinical service to Grampian, the Highlands, Orkney and Shetland.

It is one of only four fertility centres in Scotland funded by the NHS, although patients must meet certain criteria before undergoing treatment.

Alongside investigations, the centre can offer treatment such as IVF, ICSI, egg/sperm/embryo freezing and recipient, IUI, surgical sperm retrieval and surrogacy.

The science behind these processes is mind-boggling – and the clinic is also in the process of setting up a national donor bank.

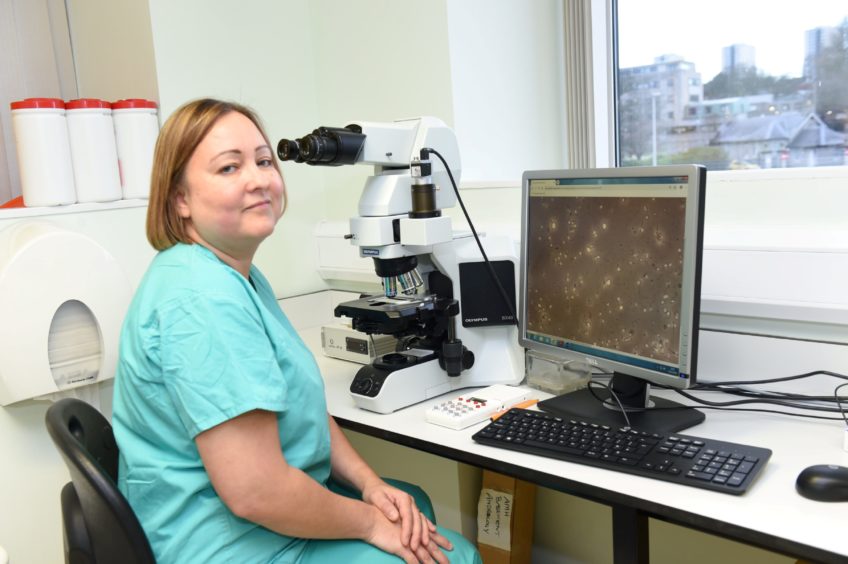

For laboratory manager and embryologist Dr Liz Ferguson, helping people to fall pregnant is all in a day’s work.

She manages a team of 11, and can usually be found overseeing work in the lab.

According to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, IVF in particular is more popular and successful than ever before.

The reasons for fertility treatment have also gradually changed across the decades, with more same-sex couples, single women and surrogates undergoing treatment.

Liz believes that women are also putting off motherhood in a bid to climb the career ladder, and can find themselves in need of fertility treatment in their late 30s.

“Increasingly these days, women want to have their career before a baby,” said Liz.

“Unexplained infertility is actually very common, and you have to factor in all the delays. So by the time someone has started trying to get pregnant, then, say, they wait another two years before coming to us for tests, age plays a big factor.

“Fertility in women can decline quite rapidly after the age of 35.

“So we always say the younger, the better – because we want patients to have the best possible chance.”

Liz and her team can watch life begin underneath the microscope, and work with exceptionally high-tech equipment.

“We have an EmbryoScope in the lab – it was funded by the Scottish Government,” explained Liz. “It is a special incubator where we can place the eggs once they have been fertilised.

“The incubator provides a stable environment where we can watch the eggs develop, hopefully into embryos.

“My job is very rewarding, but it can also be intense.

“Say we have retrieved eggs from a patients, but there are only two eggs we can use.

“That can be quite an anxious time, when you’re injecting the sperm into the egg.

“People can assume that if 10 eggs are retrieved, that means all 10 embryos will fertilise. That isn’t actually the case though, as each embryo is given a score as to how viable it is.

“We can also freeze embryos – they’re kept in liquid nitrogen in storage tanks.

“We only implant one embryo at a time, to minimise the risk of multiple pregnancies.”

The team will be told two weeks after an embryo transfer as to whether a patient has fallen pregnant, but there are still many hurdles to overcome.

“People are referred to us for a variety of reasons,” said Liz.

“We have male infertility, such as testicular damage where the patient might need surgery to retrieve the sperm.

“Then there’s endometriosis, which can make it difficult for the embryo to implant.

“It’s amazing that we’re able to help patients in the first place.

“So when a patient comes back and sees us with their baby, there’s no feeling quite like it.

“I think some patients can find it quite hard to come to the fertility centre via the maternity entrance. Especially if you don’t get the news you wanted, and then you see someone with a newborn baby.

“We do have a side entrance, but we’ll be completely separate from the maternity ward in the new hospital.

“I feel very lucky to have this job, especially when you come across people who may have been trying to conceive for years,” adds Liz.

“IVF isn’t a quick process, but when you finally have a baby at the end of it, that’s what we’re all hoping for.

“That’s what we work towards.”