With the typhoid outbreak firmly behind them, city bosses were desperate to find a way to bring people back to Aberdeen.

After three people died and hundreds more were hospitalised, visitors were reluctant to head to the north-east for fear of the infection.

But the city was clear and civic leaders drew up plans which they hoped would put it “right back on the holiday map” during the trades’ fortnight.

But the city was clear and civic leaders drew up plans which they hoped would put it “right back on the holiday map” during the trades’ fortnight.

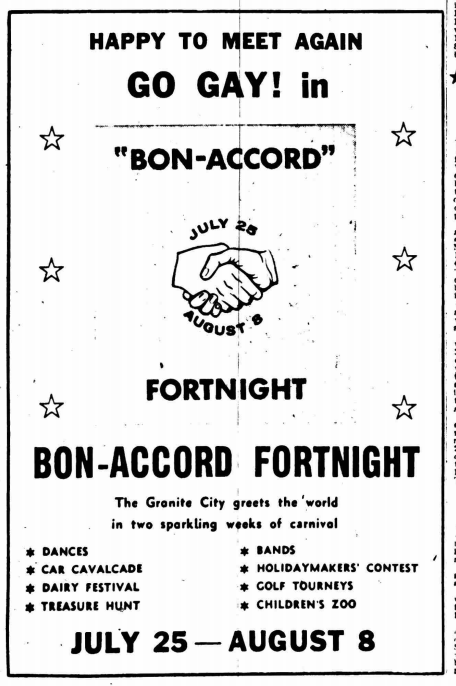

They settled upon the idea of a two-week tourism extravaganza, and would lay on a wide variety of activities and events to appeal to as broad a church as possible.

“Aberdeen for me!” the front page of the newspaper professed in the days leading up to the celebration.

“This is the reaction expected from holidaymakers, tourists and day-trippers who are caught up in the gay whirl of Bon-Accord Fortnight.

“For two weeks, all roads lead to Aberdeen, the carnival city.”

A programme of events was drawn up by hoteliers, business leaders and transport operators, beginning with a brightly-coloured parade through the city centre on Saturday, June 25, 1964.

They said: “The city will be gay with bunting and flags and the organisers are hoping ships in Aberdeen harbour will be dressed overall on the opening day.”

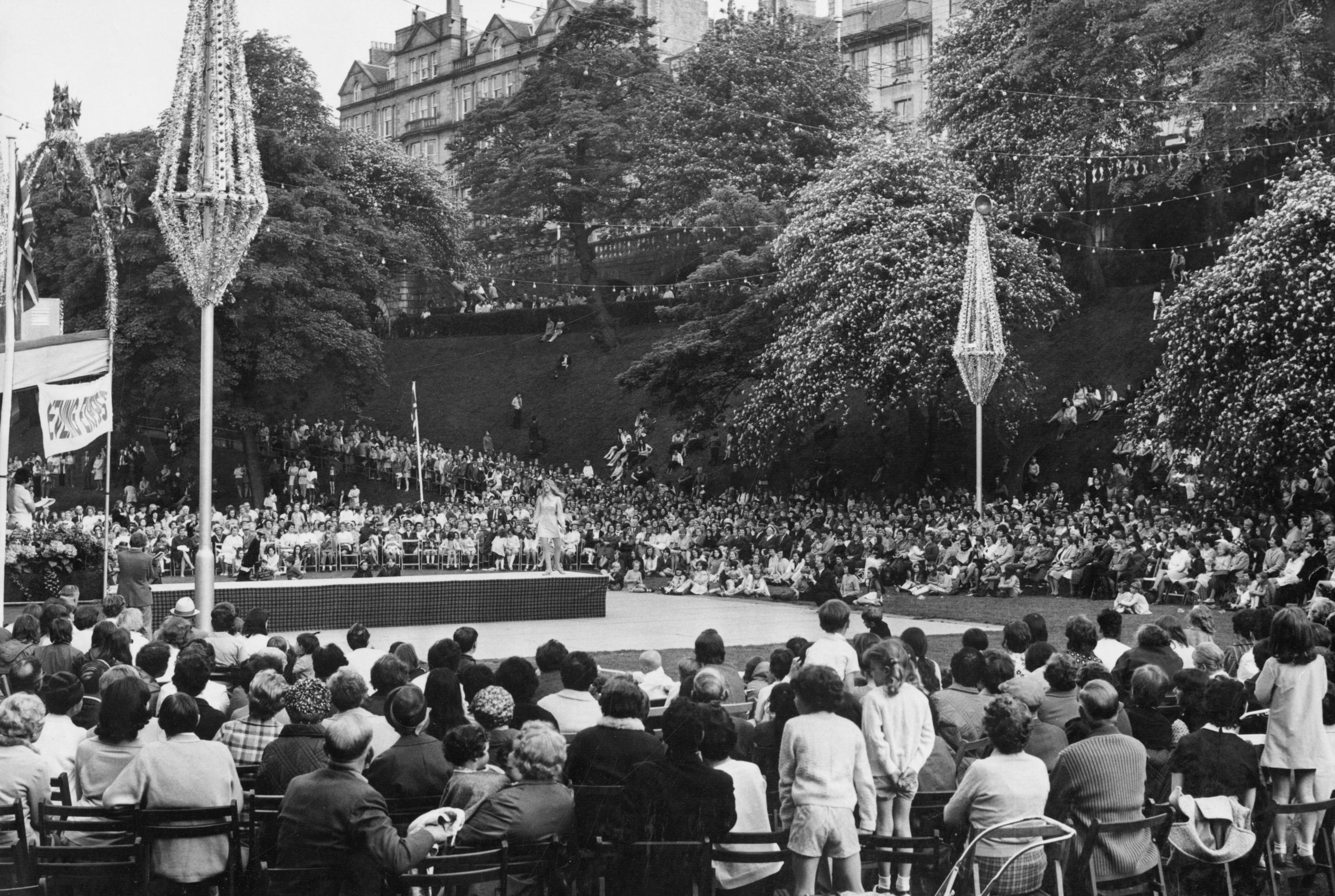

Over the two weeks that followed, pipe bands took to arenas in Union Terrace Gardens and Hazlehead Park, youngsters flocked to the beach for sporting competitions and open-air dances were held almost every night.

Crowds were also treated to a Majorettes display, a softball exhibition from US troops stationed at Edzell, and a watersports show.

It even crowned its own Aberdeen Festival Queen.

‘It has been a remarkable transformation’

The events came to a close with a celebration at the beach featuring a fireworks extravaganza and the spit-roasting of a whole ox.

At its conclusion, then Lord Provost Norman Hogg called for the Bon-Accord Fortnight, later renamed the Aberdeen Festival, to become an annual event.

He said: “There is no doubt about it that we are a city which wishes to attract as many visitors as possible, and as has been proved this year when we got reasonable weather, people are prepared to flock to Aberdeen.

“I am sure no-one would have believed two months ago that Aberdeen would have been packed out at the end of July and the beginning of August, and that visitors to the city would be unable to obtain accommodation.

“It has been a remarkable transformation.”

His words resonated throughout the city, and the Aberdeen Festival became a mainstay for decades afterwards.

In the years following, events including a canoeing regatta, horse-jumping contests and kipper barbecues were added to the agenda.

The celebrations were still going strong in 1971, when north-east journalist Gordon Casely wrote: “Music, sport, the parade and a firework finale allowed barely time for an odd production or two to be staged in the Arts Centre…

“Although the canine competition ‘Whose Dog Has the Waggliest Tail?’ emerged as something of a talking point.”

Interest in the festival did begin to wane. The Press and Journal reported in 1976 that organisers had received just 20 applications from groups wishing to decorate floats for a parade, rather than the usual 70 in the preceding years.

It also added that a children’s art competition had been launched to design a cover for a commemorative programme, but noted: “Not a single entry has been received.”

The festival continued through the 1980s, laying on entertainment including performances from Haddo House Choral Society, writing masterclasses from prominent authors and even had a visit from the Red Arrows.

It came to a close in 1993, overtaken by other city events including Aberdeen International Youth Festival.

Despite this, many still have fond youthful memories of hot summers celebrating the city’s triumph over the typhoid outbreak – hoping their children and grandchildren may be able to do the same in the coming years following the containment of coronavirus.