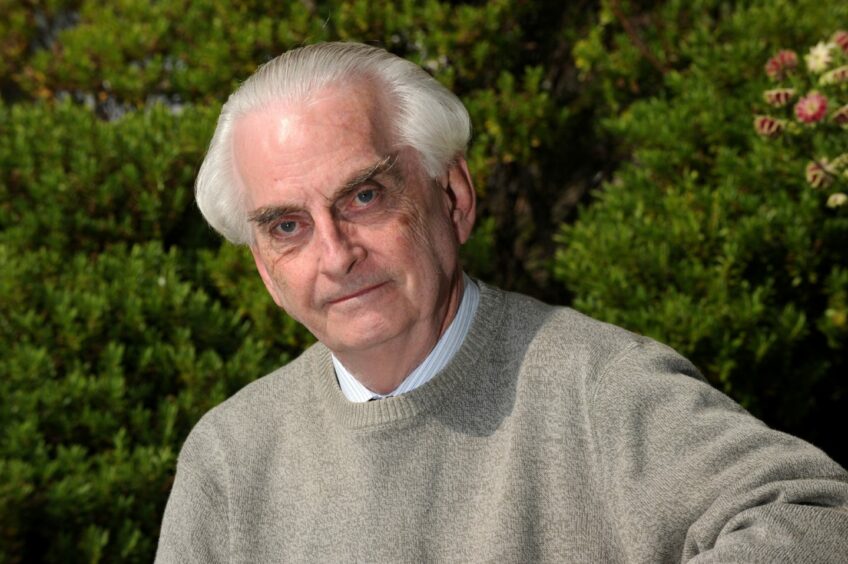

A leading microbiologist says the coronavirus crisis and the Aberdeen Typhoid outbreak of 1964 have ‘remarkable’ parallels.

As the UK settles in for its second week in lockdown, Aberdeen-based Professor Hugh Pennington said the steps taken to control the spread of that outbreak were very similar to those being taken now.

He said the city chafed under the lockdown imposed upon it but, as its people do now, understood the necessity of the steps being taken.

Professor Pennington said: “There are many differences – different bug, different form of transmission – but some of the ramifications are remarkably similar.

“Aberdeen was regarded as a beleaguered city and Aberdonians were greeted with grave suspicion when they travelled elsewhere.

“There has been an element of that happening to Chinese people who have been discriminated against due to the virus’ origins in China.

“Donald Trump, of course, has taken to calling it the Chinese virus, linking it to a geographical area.

“But just like the Aberdeen typhoid outbreak, it has had an impact outside of where it originated.”

‘People understood they had to put up with it’

For some the steps taken to reduce the impact of the spread of coronavirus will be familiar, as they were those ordered back in 1964, when Aberdeen’s medical officer of health, Dr Ian MacQueen, predicted that a “second wave” of Typhoid could strike the Granite City.

In much the same fashion, scientists and medical experts in the UK have predicted there could be a second wave of coronavirus, hitting just as people think the worst is over.

While typhoid never did return to Aberdeen, that prospect that now looms over the nation in the current coronavirus situation – and Professor Pennington said Covid-19 was far more contagious than typhoid.

He said: “Dr MacQueen was very keen on the idea of a “second wave” and used it as a stick with which to beat the people of Aberdeen so they would do what he said and stay in self-isolation.

“It is hard to predict if a second wave will come with coronavirus, due to how new it is.”

Professor Pennington said tough steps were taken to combat typhoid – many of which are or will be repeated during the current pandemic.

“The ultimate self-isolation for Aberdonians who tested positive for typhoid was that sufferers were locked up.

“There is a famous picture of a little boy being locked up – I’m unsure whether he was in the city hospital or Woodend – as facilities were made available to deal with the situation.

“They used hospital facilities for the Typhoid sufferers and while there were only 500 people who tested positive for it, that was far more than the city hospital was able to care for.

“Those who were isolated in the hospital weren’t allowed any visitors and they had to stay in the hospital until they were tested and came back with negative results.

“Women giving birth had to do so without their partners being there, which has become a traditional thing.

“People were isolated in a very rigorous way away from their families and people who were young enough to be diagnosed and remember that will recall that they were treated almost like lepers.

“It wasn’t really necessary, due to typhoid not being particularly contagious, but it was something that everyone accepted and had to live with.

“They may not have liked it – and I think today is very much the same, as people don’t like all the social restrictions, the distancing and the not going out – but people understood they had to put up with it.”

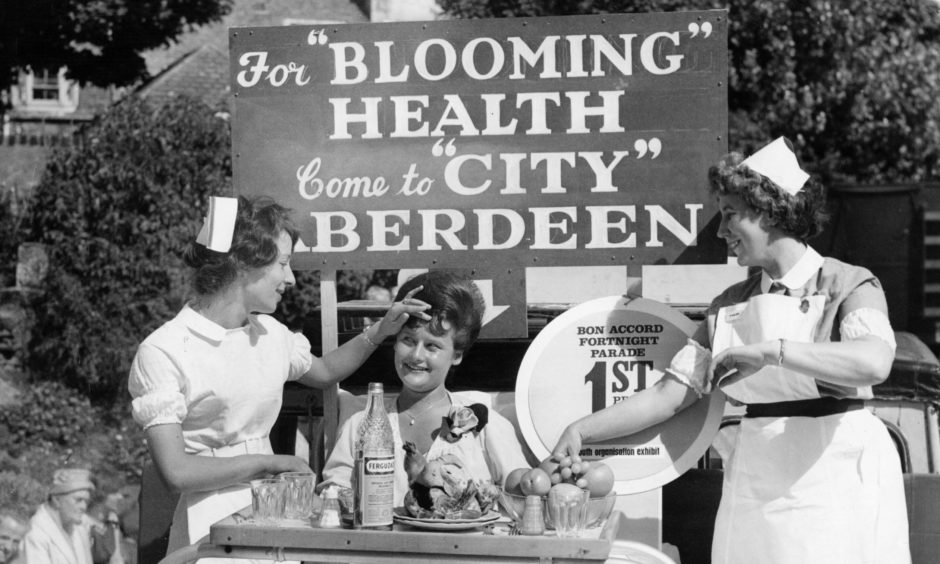

Many found the hand-washing advice surrounding coronavirus – that it should take the same length of time as two rounds of Happy Birthday – novel and unnecessary.

But it is often the first instruction issued in such medical crises.

This was the case in 1964 when Dr Ian MacQueen, the region’s medical officer of health, said it was crucial in stemming the spread of the disease – particularly after someone had used the bathroom.

In the following days, schools were instructed to ensure every child in their care was aware of the advice. They were also told to use paper towels to dry their hands, rather than those on rollers.

Due to typhoid’s incubation period, medical chiefs were hopeful that a slowing in the number of cases in late May would lead to the end of the outbreak.

But “poor toilet hygiene” from Aberdonians was believed to have led to a second wave of illness, as those infected passed it on to others, resulting in hundreds of people being hospitalised.

At the time, public toilets charged people three pence – equivalent to 22p in 2020 – to wash their hands.

But after complaints across the city, this toll was removed.

One junior doctor told the Press and Journal they had experienced a loo with no sink, but a bucket of water tied to the door handle instead.

They remarked: “It is difficult to decide whether the risk is greater from putting one’s hands into this bucket, or leaving them unwashed.”

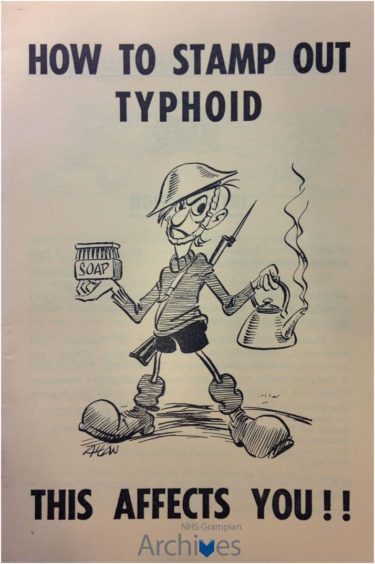

At the start of June, health chiefs issued a 12-page brochure with information on how to limit the effects of typhoid.

It was adorned with an illustration of Aberdeen Journals cartoon paperboy mascot Wee Alickie, brandishing soap and a boiling kettle, and the phrase: “How to stamp out typhoid – this affects you!!”

Inside it contained a hygiene checklist, reminding people to complete tasks including disinfecting their toilet and its pull-chain handle daily.

The outbreak soon ended, and the actions taken during it were scrutinised by a medical journal the following year.

It was decided that the disease had stemmed from a single source – the large supermarket tin of corned beef – rubbishing the initial claims of a “second wave”.

There was no proof that any typhoid cases had caught the illness from another patient.

However, it was never determined whether this was due to the step up in hygiene, the public health campaign, or a combination of both.