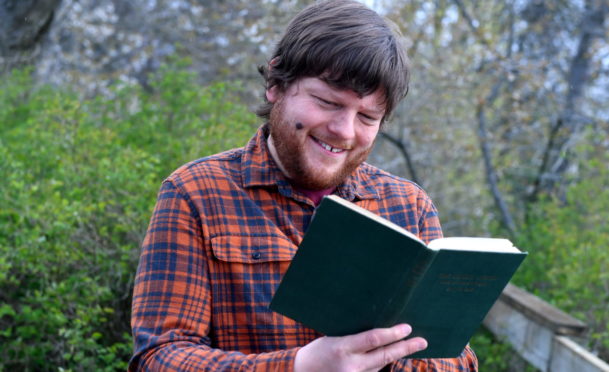

To listen to Duncan Lockerbie read out loud is to be entranced by his passion for the Scots language.

The deepening of his accent takes hold as the Doric words leap from the pages, the meaning of the ancient mother tongue only grasped by those who have grown up with the dialect.

There is a new wave however; the next generation who want to read and to speak a language that was once cause for punishment.

Previously associated with the uneducated, there was a forceful effort to ban the use of Scots language in school – with pupils physically punished if they dared to repeat the words used by their parents and grandparents.

There has since been a major investment in Scots language in a bid to prevent its extinction, from special programmes in school to Scots language initiatives at Aberdeen University.

For father-of-two Duncan Lockerbie, running Open Book sessions is a way to bring the Scots language to a wider audience.

He believes that with the world feeling tapsalteerie at the moment, words can be a wonderful way to reconnect with our past.

“Tapsalteerie has to be one of my favourite words,” he said.

“It means chaotic or upside down.

“Think of it as head over heels, only a much more chaotic and wild version.”

Duncan became involved with the Open Book sessions through his work, which also revolves around his passion for language.

He runs a Scottish poetry publishing house, which produces publications in Scots, Gaelic and English.

“I held the first session in January, and it’s the first Open Book group to be done in Scots,” said Duncan.

“I run a poetry publishing press, and I published a poetry pamphlet called Refuge by Marjorie Lofti Gill.

“It was partly based on her experience of fleeing Iran as a child in 1978.

“We got friendly and she launched Open Book sessions in 2013 thanks to crowd funding.

“She asked if I might be interested in running Scots language sessions for Open Book.

“I said yes straight away. It just seemed a good way of helping promote and support Scots language.”

Duncan believes his passion partly stems from his childhood, as he grew up hearing Doric. But repeating such words in school could lead to physical punishment.

In 1946, a report on primary education dictated that Scots was not the language of educated people.

“We don’t just need to see Scots language in print,” said Duncan.

“We need to hear it and read it.

“I grew up hearing Doric from my mum, granny and the farmers.

“I’ve been an obsessive reader since an early age. I’ve always read Scots poetry, and I’ve got my own wee collection.”

Duncan went on to study at Stirling University, where he did his dissertation on publishing in the Scots language.

“Obviously I had to research the history, and I found out things I’d never realised before,” he said.

“Scots was once a standard language across Scotland. In the 15th Century it was the language of the king.

“I didn’t know the extent of medieval Scots literature. Some of the finest canons of medieval literature in Europe wrote in Scots.

“There is a lot we don’t know about our language. It’s not a dialect or slang, it’s a rich and long tradition.

“My research pushed me on to try and make sure I could do something to help preserve the language.”

The Open Book sessions are held at Ballater Library on a Saturday afternoon, and Duncan confesses to rehearsing beforehand.

“It is slightly nerve-wracking, to read in front of other people,” he said.

“Although I grew up hearing Doric, it has mostly been something I have read off the page. Whereas most people’s experience of it is heard and spoken.

“The nature of my work means I work alone, so this has been a very different experience.

“I’ve found it quite rewarding; it’s surprising how enjoyable it is. Something so simple as reading a poem to other people. It’s the shared experience of it.

“These poems and stories come alive when you read them with others, and get a different perspective from your own.

“I’m fluent in Scots, but I still come across words where I have to refer to the dictionary.”

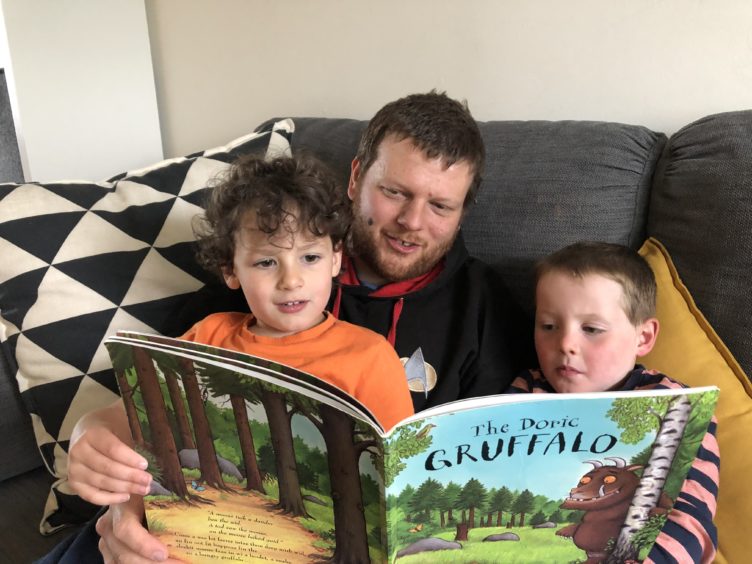

Duncan has passed his love of the Scots language to the next generation, and his four-year-old sons are huge fans of the Doric Gruffalo.

“I read to my boys a lot, there are plenty of books in Scots,” he said.

“The boys call it “speaking Tarland”. They’ll ask someone, ‘do you speak Tarland?’.

“I always find that rather funny.”

Although Open Book sessions are not currently running, you can still become involved online.

Open Book Unbound offers new weekly virtual shared reading groups.

For more information visit openbookreading.com