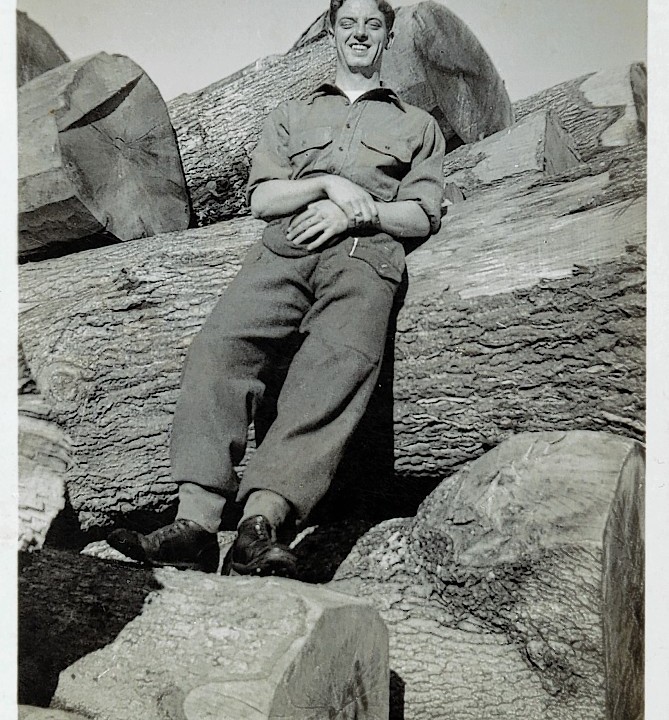

It was his first taste of war. Conscripted aged 18, Arthur Grant was taken from his life as a worker at Stonehaven’s former Glenury distillery and sent for training at the Cameron Highlander’s barracks in Inverness.

He received only six weeks training before being assigned to the Royal Pioneers Corp, and before long he was standing on the sands of Normandy.

Born on the Crathes Castle estate to a gardener father, then raised in Stonehaven, he has remained tight-lipped about his experiences of the war for most of his life.

But yesterday, Mr Grant, now 89, recalled the day he landed on Sword beach as a soldier in the largest seabourne invasion in military history.

After sailing over the English Channel, he landed near Luc-Sur-Mer, a stone’s thrown from the epicentre of British fighting at Bayeux.

Mr Grant said: “I was at this place in Aldershot leading up to D-Day, you got as much meat as you wanted in the morning, all the best grub.

“We used to say they were feeding us up for the killing. Then the day came, we had to get into the landing craft.

“Oh the scene, it was just full out, all sizes of boats and crafts, it was just a sight to behold. I was throwing sick bags over the side. I was never seasick you see, but the other boys were.

“The captain of the boat said he’d give us a dry landing, and he did.”

He said: “Eventually we got to the landing, the boy was right, we got off okay. But the smell, oh God, all the bombs and shelling, the place was just full of cordite, the air was warm with all these explosions.

“You were all right until you got up over the top of the hill. There was always shelling there.

“We were supposed to make for Bayeux, that was our rendezvous point you see and it was all just starting.”

He added: “We were ducking machine guns fire, then we got back down to the coast again and we had to hang about there for a while, one or two hours. Then had to line-up single file towards Pegasus Bridge.

“It was a hell of a job, all these dead bodies, it drives you mad. You had to hope for the best as you say.

“Boys falling down and dead bodies. I have never spoke much about it.”

He went on: “Later that night things kind of stilled down and we all lay along the side of the road. I had a boy on me, he was dead, beside me all night. We just had to lay down.

“It was a long day right enough, you was shipped away, you didn’t get anything to eat. I lived on boiled sweets.”

On the second day of the assault, as the fighting intensified, Mr Grant got caught in the midst of fierce shelling and machine gun fire.

He said: “They opened up with the artillery, I was stuck in the middle off it, and I thought this is it, and I put my head in my arms on my neck as I was supposed to do. I was pretty lucky.

“Then on Wednesday afternoon I was taken to the field dressing station. I was in hell of a lot of pain and I was awful sore needing a drink of water. It was acute appendicitis. That was me out for a couple of days.”

Mr Grant was then shipped back home after being operated on, going as far north as Sheffield for hospital treatment. He got five days of sick leave before he was sent back to France for “the push”.

Mr Grant said: “I was put back south, not far from Dover, from there it was down to the boat and back to France for the push.”

From that day until the war’s end Mr Grant would remain locked in the struggle to put an end to The Third Reich, receiving just one week of leave.

And Pte Grant of the Royal Pioneers Corp would be a corporal by the end of the European assault, fighting in Normandy until the end of Operation Overlord in August 1944, after which he moved through Belgium and Holland.

Mr Grant said: “We kept moving every day, on the move. You just slept where you we. When we was on the push, you just slept where you was on the roadside.”

He has memories both good and tragic of his time in places such as Antwerp, Breda and Goes, and of re-building a bomb-blasted bridge over the South Beveland Canal, which his family affectionately referred to as “Arthur’s Brig'”.

And the passage of time has done nothing to eliminate his memory of the day the war ended, on which he was stationed in a Dutch town.

Mr Grant said: “We was at this monastery place, and here’s all these Dutch folk dancing, and we thought “what’s going on here?” It was them that told us the war was finished.”

He married his wife Agnes, 88, in 1951, herself instrumental in the war at home, working for the RAF in England.