The screen flickers to life as the voice-over echoes, and sinister music climbs to a frenzy.

A horror movie perhaps, as dramatic scenes show exploding lava and an avalanche of rocks.

“There is now a danger which has become a threat to us all,” warns actor John Hurt, deadpan and serious.

Rock is chipped away by a chisel and a gravestone looms into view.

There is one final warning as a white lily is dropped on to a coffin lid and a single death knell rings out.

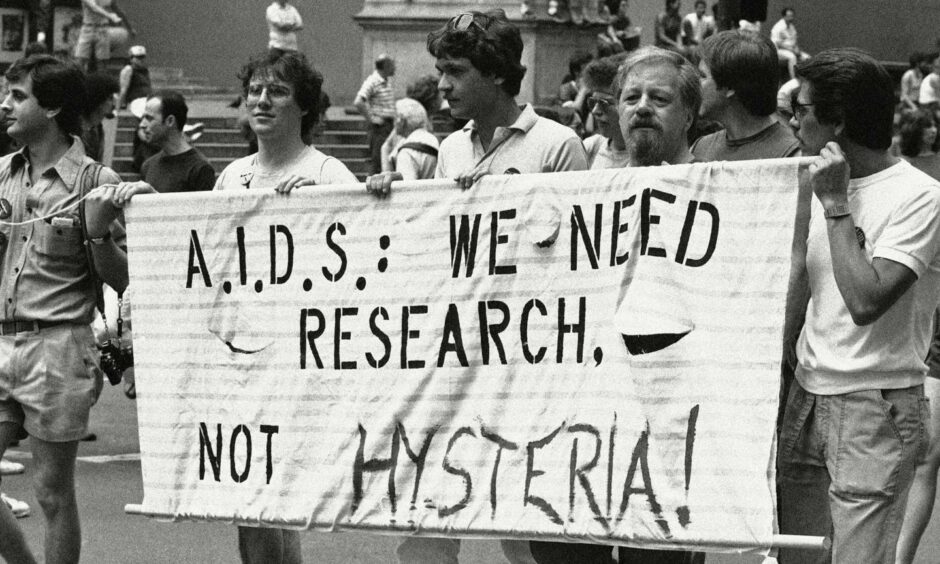

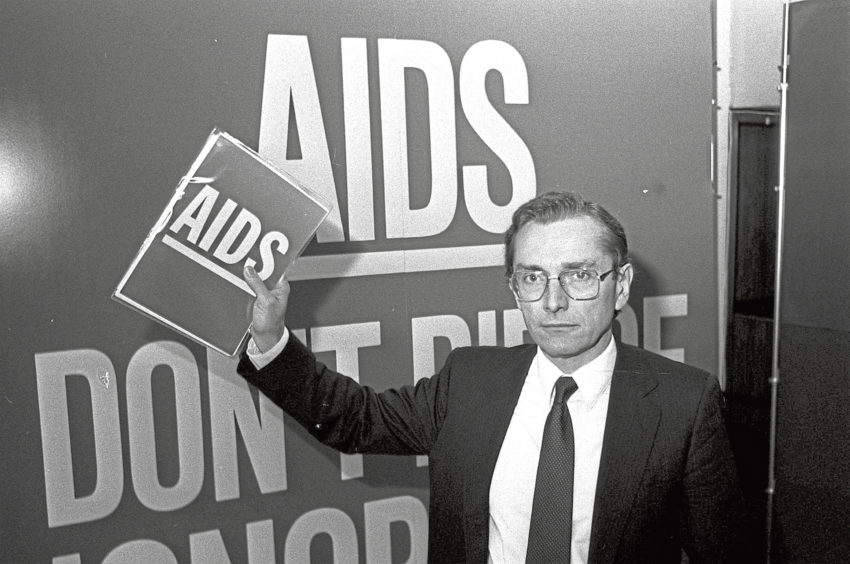

It is 1986, and public information films concerning HIV/Aids are commonplace.

Fast forward a few decades and we are now far more educated about HIV, both as a society and within the world of medicine.

Treatment has moved on, as has public opinion.

But the legacy and subsequent stigma from the world’s first major government-sponsored national HIV awareness drive has never truly gone away.

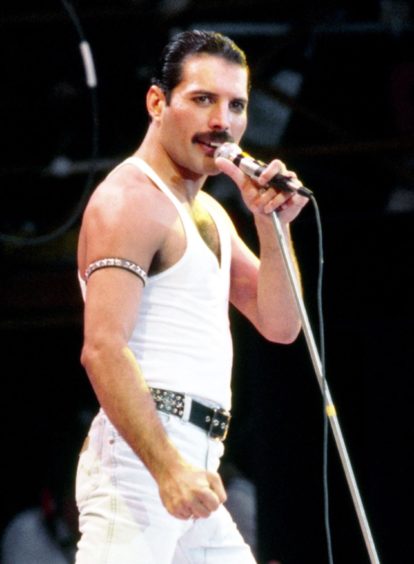

Queen frontman Freddie Mercury passed away from Aids-related bronchial pneumonia in 1991, but kept his diagnosis private until his final public statement – in which he called upon people to fight against “this terrible disease”.

We are now faced with a very different pandemic with which some parallels can be drawn.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon made commitments to eliminate HIV transmissions by 2030, as part of World Aids Day last month.

HIV Scotland, which is a leading charity, also launched Generation Zero – in a bid to achieve zero new HIV transmissions, zero HIV-related stigma and discrimination, and zero HIV-related deaths.

At a time when it would seem everything and anything is up for discussion, does stigma surrounding HIV still remain – alongside a lack of education?

A public attitudes poll, which was carried out by HIV Scotland, shows that 46% of Scots think that HIV is transmitted through biting, spitting or kissing.

We spoke with campaigners and those living with HIV who are determined to close the chapter on outdated horror stories for good.

Colin Stewart, Our Positive Voice (Grampian)

Colin Stewart likes a splash of dark humour, alongside a swift drop of bluntness.

Me and my friends always have a joke. We say ‘Let’s hope we don’t catch Covid, seeing as we already caught the other virus’,” he says, getting straight to the point.”

Colin doesn’t shy away from the fact that he is living with HIV, although he’d rather not be defined by his diagnosis.

He has built a life for himself after he tested positive in 1996, and was told he had just three months to live.

Changes in medication mean Colin now only takes one pill a day, but the stigma he faces remains largely unchanged.

Having returned to Aberdeen eight years ago, he is determined to use his experience to help others – after he and a couple of friends began Our Positive Voice (Grampian) (OPVG).

The group was set up to provide a forum for people living with and affected by HIV, after previous support networks in the area closed down due to lack of funding. The group is run by volunteers who are peer support trained, answering questions and providing support to the community.

OPVG has been instrumental in helping shape policy, and the group successfully campaigned for Aberdeen to become the second city in Scotland to sign up to the Fast-Track City (FTC) initiative.

“We really pushed to have Aberdeen become a Fast-Track City – there was a lot of banging on doors,” says Colin.

The global Fast-Track Cities initiative encouraged cities around the world to commit to action on HIV, and first launched in 2014.

“OPVG is only a small group, but that doesn’t mean we’re not mighty,” says Colin.

“We started in 2017, after Gay Men’s Health on George Street closed down, followed by The Terrence Higgins Trust closing their Aberdeen office. We were crying out for something else because there was no support.

“Part of the reason we’re a small group is because it’s difficult to get people involved due to stigma.

“If the FTC targets are reached by 2030, zero transmissions, zero deaths, zero stigma, organisations like ours won’t be needed.”

Enduring stigma

Colin has endured stigma for decades, having come out as gay when he was 20 years old.

I was 18 when I realised I was gay, and back then it was still illegal to be homosexual in Scotland unless over the age of 21.”

“I moved from Aberdeen to London in 1987, and I was having a great life.“I can remember every second of the day when it all changed, on April 29 in 1996.

“My weight had dropped to seven-and-a-half stone, and after tests I was described as having a non-negative result.

“More bloods were done and the results came on May 10.

“In a healthy person, your CD4 level, which is essentially your white blood cell count, is around 1,000. Mine was 30.

“It turned out that I had been positive for nine years prior to diagnosis but didn’t know it. There had been tell-tale signs shortly after I had become infected but I hadn’t realised it at the time.

“After I got the result, I went home and ran a bath. I got in and I just screamed and screamed. Then I got out, got dressed and went to a function. I even bid at a charity dinner, I was on autopilot.”

“I wanted one last night with my partner before I destroyed our world. I cancelled my pension plan and went on this mad holiday, backpacking through the jungle in Malaysia. I thought this was my final farewell.”

Medical advancements

“In April this year, it will be 25 years since my diagnosis and 34 years since I contracted it.

“I immediately started on the only drug that was available, AZT. The side effects were awful. Later that year, the antiretroviral drugs came out, and one of them was called Ritonavir.

“It was really potent and it turned out to be the drug which saved my life. But at the time I didn’t think I would recover.

“In those days, once you were diagnosed you weren’t put on treatment until your CD4 fell to around 200.

“Nowadays, with all the advances in treatment and the fact that the meds don’t have the same awful side effects, you start on treatment immediately. This protects your immune system and reduces the amount of virus in your body (viral load).”

As the months turned into years, Colin realised that living with HIV was, in fact, possible. But while medicine evolved, people’s opinions did not.

“The damage from the tombstone advert was everywhere, and talking to someone about my diagnosis was always a nightmare,” he says.

“I didn’t know how the person was going to react, and invariably I’d end up comforting them.

If I was visiting friends with children, I’d see the look of panic on their face when I was holding their baby. I became really sensitive to it.”

“After me and my partner broke up, I always told anyone I was seeing that I had HIV so they could make a decision before we slept together.

“After finding out, people never wanted to take things further. That’s why the U=U campaign is so important – Undetectable = Untransmissible.”

Changing attitudes

Our Positive Voice (Grampian) worked with Public Health and NHS Grampian to spread this important message regarding HIV transmission. When treatment is taken as prescribed, it can reduce the level of the HIV virus in the blood to such a low level that it is undetectable.

When that level is reached for six months, the virus is untransmittable.

“We don’t want to encourage people to have unprotected sex, but we do want to change people’s attitudes,” says Colin.

A recent survey conducted in Scotland showed that 90% of those surveyed believed that they were informed about HIV.

However, when asked if the following statements were true or false, more than 50% of those surveyed thought they were false.

Someone taking treatment who has an undetectable amount of the HIV virus in their body cannot pass on HIV to their sexual partners.

There is a pill you can take that prevents HIV infection.

Both of these statements are true.

“We need a public campaign by the Scottish Government to get rid of the myths and misinformation, and to combat the huge lack of education.”

“HIV is still thought of as a gay disease, but figures from 2019 show that more heterosexual people were diagnosed than homosexual in the Grampian region.

“HIV can affect everybody, and it’s also everybody’s responsibility.

It is said that the only way to beat Covid is if we all work together. The same can be said of HIV. The difference is that Covid affected everyone, whereas HIV is thought to impact the minority, but that is not true.”

“We need TV ads, press ads and closed caption video clips on social media.

“We need a new infomercial, because even those working within the NHS can have a lack of knowledge. In 2014, I was placed in a private room at Woodend Hospital – I was there for a hip operation. A nurse told me I was in a private room because I had HIV, and I might bleed everywhere.

“I thought she was joking.

“NHS staff can’t know all the information about every condition, disease and virus – it is the same for members of the public. That is why it is important to raise awareness of HIV and dispel the myths and reduce the stigma.

In 1996, I took about 186 tablets a week,” he says. Now I take six tablets a day, and only one of those is for HIV.

“It is not a killer virus anymore – I’m proof you can lead a full life.”

“There are a lot of people out there who are HIV positive but don’t know it. If we can get those tested and diagnosed, on medication and with an undetectable viral load, we can stop the spread of the virus.”

Lost generation

More than 5,000 people are living with HIV in Scotland, and late diagnosis is still a problem.

Chief executive of HIV Scotland, Nathan Sparling, believes there is a “lost generation” who were never educated on HIV.

“There never used to be a strategic focus to end HIV in Scotland, there were no targets,” says Nathan.

“When we reach zero transmissions and zero deaths, that’s when we as a charity won’t need to exist any more.

Our public attitudes report shows that there is a lost generation. It’s people under 35 who don’t have the knowledge, but their attitude is more progressive.”

“By the time you get to the 65-plus age range, it’s the other way round. Their knowledge is better but their attitude is worse.

“Does a stigma still exist? Absolutely, it manifests itself in lots of different ways. One of the main things is fear.

“It’s fear that stops people from getting tested. They’re scared because they think it’s a death sentence. They still think HIV can be passed on by touch.

“It can also depend on which community you are from. Whether you’re transsexual, a sex worker or drug user, you already have a stigma. Add on HIV and it becomes multi- layered.

“We need to educate young people, but it’s not as easy as saying ‘Let’s teach it in schools’, as we’re focusing on people up to the age of 35.”

The charity’s next big aim is a TV advert, far removed from the original campaign.

“There hasn’t been a TV advert concerning HIV since the 1980s, and yet there has been plenty of Covid adverts,” says Nathan.

As soon as something changes, no one is talking about it. We need people to know that HIV has changed.”

“The previous message was to scare the living daylights out of people. Then treatment became available and there were no adverts of people living with HIV. That’s the failure, we need a widespread public campaign.

“We’ll never not talk about Covid.

“The problem is that we haven’t had the same attitude towards HIV. In turn, the stigma is disabling society – it’s not HIV itself that is the problem.”

Remarkable changes in treatment means medication has reduced to as little as one pill a day.

Nathan believes that even those working in healthcare need to be educated, however, due to the symptoms of HIV going unrecognised.

“Treatment is incredibly effective – it’s not the cause of a lot of people’s worries anymore,” he says.

“We know from anonymous blood samples that around 500 people in Scotland right now are living with HIV without knowing it.

“So there is still so much work to be done.”

What are the symptoms of HIV?

Most people infected with HIV experience a short, flu-like illness that occurs two to six weeks after infection.

After this, HIV may not cause any symptoms for several years.

The most common symptoms are a raised temperature, sore throat and body rash.

The only way to know for sure if you have HIV is to get tested.

-

To find out more about Our Positive Voice (Grampian), visit www.ourpositivevoice.org or phone 01224 968468.