The daring rescue of a shipwrecked schooner’s crew is the inspiration for a new public artwork by the “Stonehaven Banksy” – the first to be located outside his hometown.

Based on the fate of the Banff-based Isabella in a deadly gale that lashed the north-east in November 1888, the distinctive metal model is now finished and ready to be installed on the clifftops at Newtonhill.

Bid to boost pandemic-hit local businesses

It was commissioned as part of a community-led project to bring in visitors and help the post-Covid recovery of the local pub, café, restaurants and other businesses.

A series of linked walking routes taking in the village’s picturesque surroundings and rich coastal heritage have also been drawn up which will be featured on a new website and Facebook page: Newtonhill and Beyond.

It carries details of businesses and voluntary groups, maps and guides to the walks, historical information and community updates for the village and nearby Muchalls and Chapelton.

The initiative is among several selected for funding by Aberdeenshire Council’s Phoenix Fund programme, which is aimed at boosting economic recovery in several town and village centres.

Among outfits closely involved in getting it off the ground are the Skateraw Store café and shop, the Newton Arms pub and the Bettridge leisure centre – all of which have played big parts in getting the community through more than a year of lockdown.

Where did they appear from?

When mystery sculptures started appearing overnight along the seafront at neighbouring Stonehaven several years ago, they caused a stir and received national and international attention.

The man behind the intricate nautically-themed models. which remain a very popular sight, was later revealed to be Jim Malcolm, who was commissioned to create another for the village just a few miles up the coast.

He says he is now very much looking forward to an early morning visit once the model is in place to photograph it with the rising sun.

At more than 1.7 metres in length – and needing at least two people to lift – it is almost twice the size he originally intended.

“When I make things I have a rough idea what it’s going to be but it often ends up different,” he says.

“I read the story and looked into it and it just developed. Once I got going I just got into the zone and away I went.”

“But I’m really very pleased with it, especially as it’s the first schooner I have made.”

The finished craft has been kept under wraps while lockdown continued and businesses were closed.

But the easing of rules means it can now be installed at its permanent clifftop home, overlooking the harbour where the Isabella’s ill-fated journey home finished in disaster.

A planned open day celebrating local groups and businesses and promoting the village will now take place at a later date, once restrictions are lifted further.

It forges a link from Skateraw of the past to Newtonhill and Beyond of the present and future

Alan Jones has chaired a small team working on the plan for months – with the support of Newtonhill, Muchalls & Cammachmore Community Council.

He tells us: “It has been a privilege to have worked with a dedicated and enthusiastic team in making this happen in challenging circumstances”.

Also celebrating the potential of the project are Jamie Donald and Anna Hall, who had not long opened Skateraw Store when the pandemic hit and are now looking forward to being able to welcome people back properly after a year of takeaways and deliveries.

“From the very start of the project we wanted to come up with something that was for the people of the village but would also attract others from far and wide.

“We are excited to see the sculpture in place. It will be a great focal point for the walks and people visiting Newtonhill for many years to come.”

Councillor Wendy Agnew, chair of Aberdeenshire Council’s Kincardine and Mearns area committee, says lockdowns have had a “particularly hard impact on our town centre economies which were already facing multiple other challenges.

“Aberdeenshire Council developed the Phoenix Fund to help some of our town centres to recover and attract footfall back to local businesses and I look forward to seeing the benefits to the local community.”

Vice-chair and Newtonhill resident Ian Mollison adds: “I am particularly excited to see this project coming to fruition. By extending the work of Stonehaven’s Banksy out along the Kincardineshire coast, it will encourage more visitors to come to the area, enjoy a healthy walk and spend time in our local shops here in Newtonhill.”

And in the words of Newton Arms landlord Ian Beresford: “This has been a fantastic project, paying tribute to the courage and kindness of the good folk of Skateraw and the bravery and seamanship of the crew who brought the vessel to shore.

“Jim Malcolm’s sculpture of the Isabella is a lasting work of art of which Newtonhill and the surrounding area can be proud. It forges a link from Skateraw of the past to Newtonhill and Beyond of the present and future.”

A ‘mountains high’ sea, an ill-starred skipper and a gallant band of locals: the story behind the sculpture

It was a journey The Isabella had undertaken countless times in the 11 years since she was bought by a Banff coal merchant named Watson for the grand sum of £750.

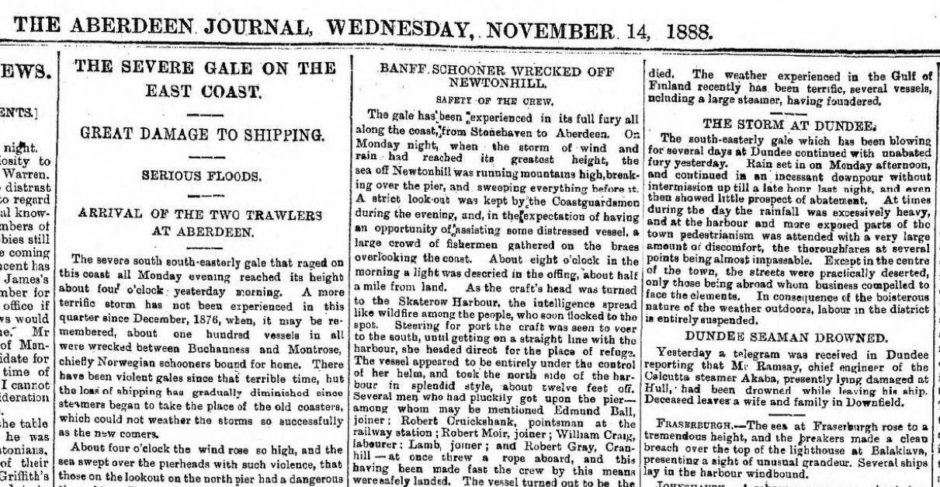

Setting sail from Sunderland with a full cargo on Monday, November 12, 1888, the schooner’s five-strong crew were anticipating a relatively smooth sailing back home to the north-east.

They reckoned without the intervention of one of the most ferocious storms to hit the coast for a decade – or indeed without the captain’s chequered history of navigating such choppy waters.

George Lyall had been wrecked twice before and nor would this, tragically, be the last time that fate befell him.

Conditions rapidly deteriorated on the passage north and the heavily-laden 93-tonne vessel, which had made an aborted attempt to seek refuge in the Firth of Forth, began to take on water – a problem that had reached crisis point by the time the Girdleness Lighthouse came into sight at 4am.

Tacking and drifting for hours, when daylight finally illuminated the scene, the Isabella could be seen close to the shore at Newtonhill, perilously close to the jagged rocks of Craig Stirling.

A monumental effort by Lyall and his mate William Roy somehow steered the stricken boat clear and into the small harbour, where a “gallant band” of villagers had gathered.

All the appearance of a mighty waterspout

The prospects of a rescue did not appear promising.

With the south-south-easterly gale still blowing with full fury, witnesses described a sea “running mountains high, breaking over the pier and sweeping everything before it”.

Along the coast in Aberdeen, a huge crowd had also gathered, defying 50-foot spray “with the appearance of a mighty waterspout” to watch several other ships try to reach safety.

The arrival of steamers over the previous few years had reduced the threat to seafarers of such dreadful conditions, but there remained many still travelling under sail like the Perth-built Isabella.

Back at the harbour in Newtonhill – still known by many then as now as Skateraw – the schooner had got close enough to the pier for a rope to be thrown by a “gallant band of volunteers, hanging on by the rings on the pier to keep themselves from being washed off by the tremendous seas that swept every new and again over it”.

One by one the crew were able to get themselves, hand over hand, to the relative safety of the pier despite the crashing waves threatening constantly to send them flying into the waves.

Leaving the deck last, Lyall was indeed knocked backward by a breaker and only saved from a certain drowning by first one and then another of the locals grabbing a foot each and pulling him to safety.

‘Intense dissatisfaction at the imputation of cowardice’

The report in these pages at the time records two very distinct impressions of the role played by the fisherfolk of Skateraw.

On the one hand it was acknowledged that they treated the rescued seamen “with every kindness” after taking them to their cottages ranged in a row from the Braehead.

But if labourers, railwaymen and joiners were named among those directly involved in the bravery, it was said that “the fisher folks displayed a lamentable reluctance to endanger their own personal safety in getting them to land. Not one of them ventured on the pier to assist when their presence would have been most welcome. They hung back, encouraging the others and comforting their women folk.”

This stung – not least when as much was entered later into the official report of the incident.

Indeed so deep was the hurt and so intense the umbrage taken at the slur, that the following year they went as far as to employ a certain Major W Disney Innes of Cowie – “universally recognised as the fisherman’s friend” – to conduct an investigation in a bid to clear their name.

Among the findings which most pleased them was that “credit is due to them for the promptitude” with which they had in fact rushed to Muchalls in search of emergency equipment.

Nothing left to save

Back at the scene of the drama, the Isabella had been thrown onto her port side, her valuable cargo “clean washed out” and was clearly becoming beyond salvage.

Lyall managed to get himself aboard in a vain bid to stow the sails and recover anything he could, to the fury of the coastguard, Commander Davies.

The skipper “turned a deaf ear” before he was “virtually placed under arrest”, marched to the station and put on a train home.

What wreckage remained from an event which has gone down in village memory to this day, was sold to a Mr Marr, an Aberdeen chandler for £13 – just over £1,000 today – and local man John Christie snaffled any remaining coals for the princely sum of 10s.

As for Lyall, eventually there came one such drama too many.

Less than a year later, in October 1889, he was captain of the Wetherill when it got into trouble in stormy seas and was lost off Whinnyfold trying to make refuge at Peterhead.

A crewmate who helped him after they were flung into the icy sea then lost sight of the ill-starred captain and, despite running “as fast as his bare and bleeding feet would allow” across rocks to get help from a crowd of fishermen returning from church, could do no more to help.