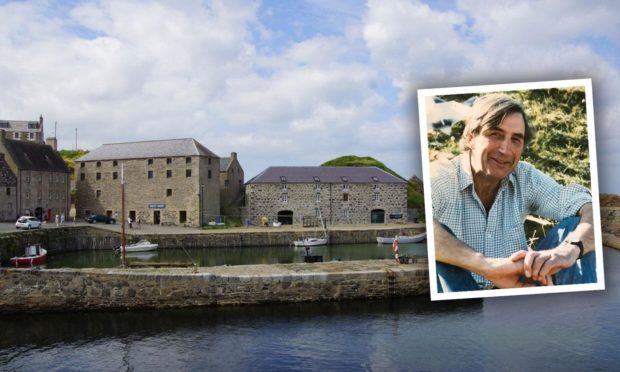

A kind-hearted businessman has left historic listed buildings at Portsoy’s picturesque harbour to a local conservation group in his will.

Tom Burnett-Stuart, who died last January, has ensured that the listed structures will be enjoyed for generations by leaving them in the care of the North East Preservation Trust.

The four buildings recently formed the backdrop to an episode of Peaky Blinders and featured in the remake of the film Whisky Galore.

The 85-year-old’s dying wish that they be returned to the community to be looked after has been hailed as a “remarkable act of generosity and care for the people of Portsoy”.

It is now likely that locals will be consulted on the best future use of the buildings.

‘They will benefit the town’

NESPT chairman Marcus Humphrey said: “We are enormously grateful to Tom Burnett-Stuart for his generous bequest.

“We look forward to working with the executors and the Portsoy community to conserve the beautiful buildings and bring them back into uses that benefit the town.

“My great thanks also go to the estate executors, Alastair Robertson and Jacky Player, who have worked tirelessly to allow a smooth transfer of ownership of the buildings to the NESPT.”

Mr Robertson said “I am delighted to see these wonderful buildings being put into the care of the NESPT.

“They have a strong track record in building conservation and adaptation.”

The buildings are –

- The category A listed Portsoy Marble Warehouse designed by John Adam

- The B-listed Portsoy Marble Workshop

- The Granary Building, which is also B-listed

- And the category C listed “Rag” Warehouse.

The buildings are largely unused, although the Marble Warehouse has a popular shop on the ground floor, which is open on Fridays and Saturdays, and the Portsoy Pottery on the first floor.

Poignant gesture

The bequest also includes two self-catering holiday cottages at the port, three empty and unused cottages in Whitehills and a “sizeable” sum of money to be used to “protect the architectural integrity” of the harbour.

As well as protecting and conserving the buildings, the bequest secures the future of the NESPT.

It is hoped that the legal process will be completed and ownership transferred by the end of the year.

The announcement comes on a big weekend for the town, with the Scottish Traditional Boat Festival taking place virtually.

‘An easy manner and an infectious sense of humour’

Profile of Tom Burnett-Stuart by Alastair Robertson

In spite of his patrician tones Tom Burnett-Stuart was every inch a Banffshire man with a deep respect for its people, culture and in particular its traditional buildings.

As the younger son of landed gentry from Marnoch he might have been expected to find a job in the city or running the family estate.

But after Eton (he had first attended Marnoch School), National Service and a spell in the steel industry, plus a diploma in engineering he came home in his twenties to make a living in the burgeoning Scottish tourist industry.

Initially he investigated everything from motels in the Highlands to the manufacture of evil-smelling tartan fibreglass trays in the basement of his mother’s home.

Finally, recognising the unique properties of the marble-patterned serpentine rock that came from the cliffs and beaches of Portsoy he learnt how to polish and cut the unpromising looking grey stone to reveal its distinctive deep reds and greens.

He was reviving a local industry. Portsoy marble had been a major export in the 18th century and was reputed to have been used for fireplaces at Versailles (Tom searched the entire palace in vain, he admitted, although it was certainly used at Hopetoun House).

He bought his first building behind the imposing Corff House, which now houses the Portsoy Marble shop, for a few pounds in 1964 and established a workshop turning out polished stone gifts and jewellery employing the late George Macrae and Jimmy Merson while John Watson became an expert carver of animal figures.

The hair-raising, if ingenious, range of pulleys, polishing machines and electrical wiring he rigged up would give today’s health and safety inspectors nightmares.

While the business grew, and Portsoy Pottery was started with Brian Shand the shop was run by a succession of devoted “girls” as he called his local ladies who happily put up with his often-idiosyncratic ideas of display and marketing.

Gradually he bought up surrounding semi-derelict buildings as they became vacant – at the right price.

For he was an inveterate bargain hunter and dealer at heart who hated to see anything go to waste.

He would invariably return from the town tip with more than he had taken.

No farm roup or auction sale was complete without Tom, no abandoned quarry left unscoured for old lintels, dressed corner stones, joists and “useful bits” of redundant machinery hauled home in a succession of battered Mini Pickups later supplanted by equally abused VW vans.

Yet everything was earmarked for a purpose. He was deeply appreciative of the skills and techniques of local joiners and masons.

He became an early champion of the then almost lost art of lime harling (render) and heartily disagreed with most of the official conservation bodies over its correct mix and use.

For he undoubtedly possessed a “thrawn” or stubborn streak.

Fortunately, this was leavened by an easy manner and infectious sense of humour.

It was never certain he had a clear idea what he would do with the buildings – 6 and 7 Shorehead are now popular holiday cottages – but of one thing he was sure, they should be conserved and brought back to life using local skills and not fall into the hands of others with no grasp of local building tradition.

Consequently, Shorehead has become a sought-after period film location, last used this winter for Peaky Blinders.

His crowning success completed shortly before he died was the restoration of the old Shorehead grain store.

He was particularly proud of the new windows, not least because he doggedly tracked down a maker in France who could produce them 40% cheaper than anyone in the UK and which he collected in his VW van from Calais.