Famous for its 400-strong colony of seals, nesting terns and beautiful sandy dunes, Newburgh Beach has recently become home to another, less pleasant resident: nurdles.

Tiny pieces of plastic no larger than a lentil, nurdles are what plastic drinks bottles, bags, food containers and even car parts look like before they are processed.

But instead of being on a factory floor ready for manufacturing, thousands of these plastic pellets are turning up on one particular north-east beach.

How did nurdles end up in Newburgh?

The short answer is, no one knows. But marine biologist Dr Lauren Smith who lives just minutes away in the town has been puzzling over it for the last few months.

“There is one little spot we seem to have and for some reason, all these little pellets are starting to accumulate there,” she said.

“You can do a clean there one day and the next day you’ll find just as many all over again.

“So I’m not entirely sure why they’re accumulating in this spot… But there are absolutely thousands of them.”

Many of them will have been accidentally dropped into the ocean while being transported.

Often they are taken around the world in large sacks, and even the smallest tear in a bag can result in millions of nurdles ending up in places they shouldn’t.

“They can also travel through drainage systems,” Lauren said, meaning that pellets can eventually flow out through rivers and into the ocean.

How big is the problem?

Because you can’t easily see them, it’s easy to assume that nurdles aren’t a big problem.

On a typical beach clean, people always rush to find the biggest bit of litter they can find, Lauren explains. But as soon as she tells them that these small bits of plastic usually harm animals faster, the realisation dawns on them.

“Micro-plastics like this are so easily distributed around the marine environment that it’s very easy for them to get into the food chain,” Lauren said.

“Whether that’s through fish or birds etc eating them and then other things are predating on them, it’s very easy for them to accumulate in large quantities in the bellies of animals.”

The plastics become trapped in their stomachs, often making animals feel full and stopping them eating real food. This can lead to starvation and eventually death

Very little research exists to quantify exactly how many of these tiny pre-production pellets end up in the environment.

Estimates which do exist tend to be isolated by country (a recent study found production facilities in the UK lose between five and 35 billion pellets a year ) or specific incidents which make the news, like the time two shipping vessels collided and spilt 49 tonnes of plastic pellets into the sea off the coast of South Africa.

How to know if you’ve found a nurdle – and what to do about it

Nurdles are very small and usually an opaque white or yellow colour. This makes them incredibly difficult to spot if you don’t know what you’re looking for.

“It’s one of those things that once you’ve actually found one, then you start to notice more and more and kinda get your eye in for them,” Lauren said.

“Most of them are white or off-white in colour so they blend in quite well to sandy environments.”

With her, Lauren carries an old jam jar three-quarters full of nurdles, all picked up on previous beach visits. Some are blue or yellow, while others are red or even black.

They are all meticulously counted, with well over 2,000 individual pellets currently in the jar.

But it’s not as simple as just scooping up a handful of pellets, each has to be picked out of the sand one by one and you need to be careful what you’re touching.

“Nurdles are known for accumulating chemicals and also releasing chemicals into the environment,” said Lauren, “so you should wear gloves if you are going to look for nurdles and clean your hands properly after.”

A thankless but important task

Although nurdles start out small, over time, like other plastics they will become weathered and fragment into even smaller particles.

Picking them up is therefore incredibly important, but it isn’t a job that wins much praise.

The small and relatively unknown nature of nurdles means that most people will never know the hard work it takes to remove them from Scottish beaches.

Lauren doesn’t mind. “Sometimes it’s just, you know, feels like just a tiny little drop in the ocean, or a tiny little pellet in the ocean I should say, but it’s so important to keep on top of this,” she said.

“Ideally yes, this needs to be stopped a source. We don’t need all of this plastic going into the environment, but at the end of the day, you can do your bit and remove it.

“The animals here at Newburgh don’t deserve to have this man-made plastic just dumped in their habitat, so if we can pick them up it’s a great thing to do and can only be a positive thing.”

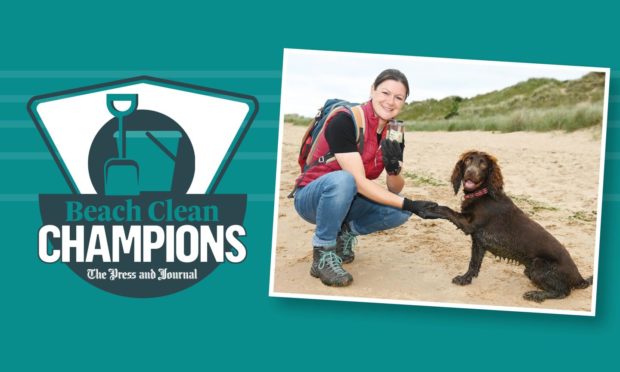

Dr Lauren Smith has have nominated as one of our P&J Beach Clean Champions.

Find out more about our Beach Clean Champions project and read about our other nominees below.