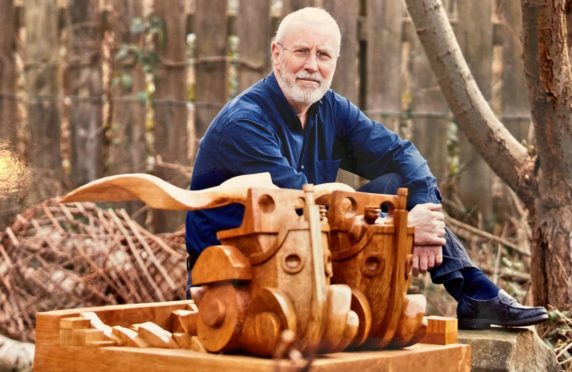

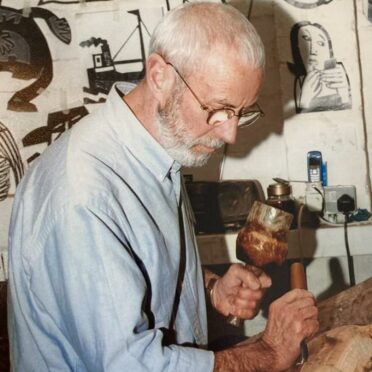

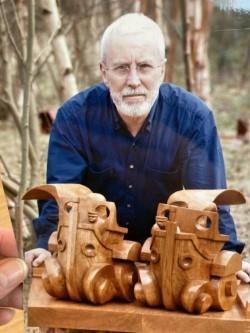

Sculptor, carver and former Mearns Academy art teacher, Iain Redford McIntosh has died aged 76 after contracting Covid.

We look back on the life and lineage of one of the North-east’s most celebrated artists.

Born on January 4, 1945, in the room above Hanover Street’s grocer’s shop in Peterhead, he was the only son of cabinet maker James McIntosh and wife Barbara Barron.

But while he was destined to craft wooden items later earning himself a place in the prestigious Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, it wasn’t the woodwork career his father had hoped for.

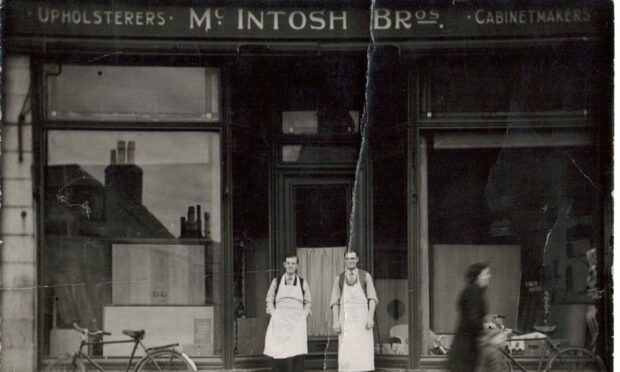

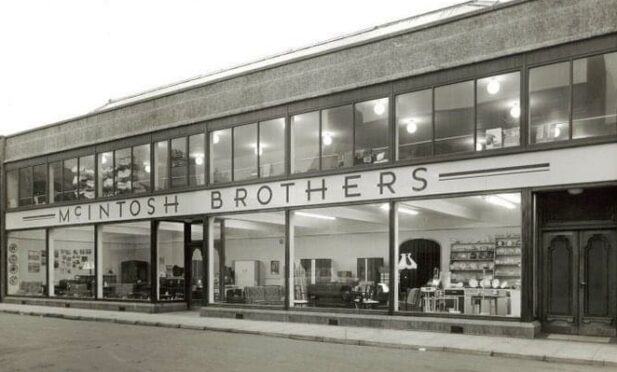

Family business

Iain’s dad was one half of the duo behind McIntosh Brothers’ Home Furnishings.

With stores springing up all over the North-east it was expected that Iain would follow suit and join his dad and uncle Bill.

But a passion for sculpting, rather than cabinetry, would take him away from the family business, and even Peterhead itself.

Both were frowned upon as the North-east fishing town was home to both sides of Iain’s family.

Roots

Ian’s parents were married on November 16, 1935 in Peterhead’s Episcopal Church.

James was 26 and a journeyman cabinet maker from Threadneedle Street and Barbara was a domestic servant, aged 28.

As well as Iain, the couple would have two daughters: Morag – who died shortly after birth due to heart complications from Down Syndrome, and Sheila, who passed away in 1939 from cervical cancer.

Loss in the lineage of the McIntosh and Barron families.

Peterhead bombings

On Sunday, September 21st, 1941, 30 people were killed in Peterhead, their deaths attributed to ‘war operations: Bomb Explosion’.

Among those were the family of Iain’s mum, Barbara.

With Sheila in her arms, Barbara and James turned the corner into James Street just as the squeal of a German bomber loomed overhead.

Protecting his wife and young child James ushered them into a doorway en-route to a family gathering further up the street.

As the bomber let loose his hold of bombs, house numbers five, seven, nine and 11 were completely destroyed.

Iain’s maternal grandfather – 69-year-old William Barron – his wife Isabella, their sons, daughters, grandchildren, aunts and uncles were all wiped out instantly as Barbara and James looked on from down the street.

Iain later records in his memoirs that although his mother was spared her life, he believed the impact of the bombings marred her as a mother.

He wrote that her aggression and coldness towards him meant news of her death in 1981 was met with very little sadness.

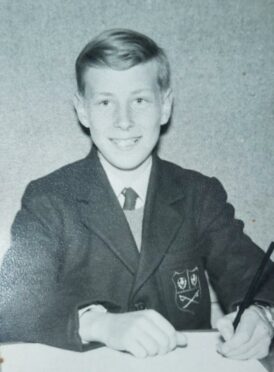

School days

Iain attended St Peter’s Episcopal Church School where he received multiple end-of-year prizes and became ‘quite good at country and highland dancing.’

Peterhead Academy, followed, which Iain described as ‘an unpleasant shock’, before he defied his parents to attend Gray’s School of Art, Aberdeen in 1962.

He did come home at weekends, however.

Even promising artists need to earn money, so a Saturday job in the family furniture store beckoned.

He thoroughly enjoyed his university days despite finding himself exiled in Garthdee’s architecture school during Aberdeen’s 1964 typhoid outbreak.

Allegedly stemming from a can of William Low’s corned beef, 400 people were affected and the art students disrupted.

In 1967 Iain undertook further study at Aberdeen Teacher Training College which opened the door for him to become principal art teacher at Mearns Academy, Laurencekirk, where he worked for 17 years.

A family of his own

On April 6, 1968 Iain married Frieda Crisp of St Andrew’s, a fellow Gray’s student.

Five months pregnant with their daughter Sally, the couple would remain married for 35 years and go on to have a second daughter, Emma.

Iain raised his family in a detached cottage with a workshop in Powmouth, near Montrose.

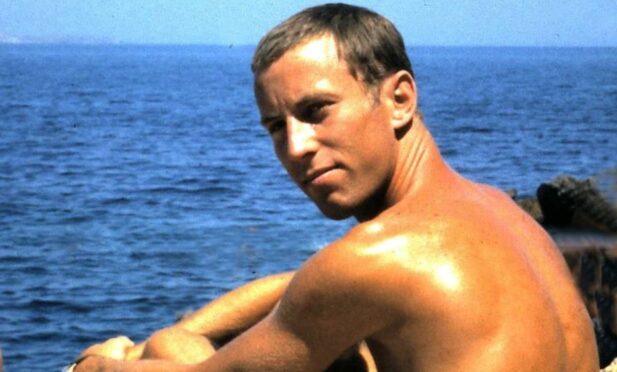

The girls would unleash a sense of fun in their father, who would love taking his daughters on foreign holidays, where snorkeling and packed-dinghy adventures awaited.

Sally and Emma would both also usher in a new season of joy for Iain; his days as a grandfather to Ryan, Rio, Angus, Archie and Rebecca.

Following the breakdown of his marriage Iain found solace in the company of Mhairi Macdonald Greig, who became a long-time friend.

Awards

Iain received numerous awards over the years starting in art college where he was given the 1965 Queen’s Award for Art and Design and the 1967 RSA Carnegie award.

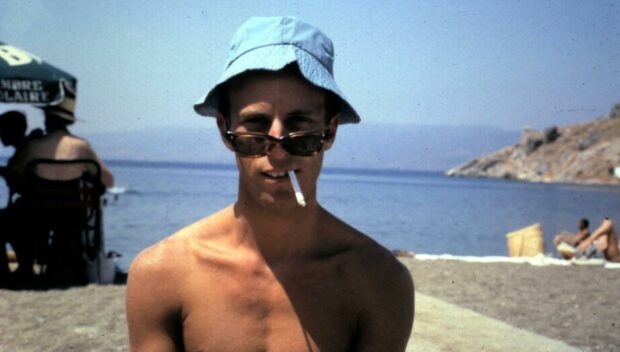

In 1966 Iain gained his Diploma in Art and also the George Davidson Travelling Scholarship allowing him to visit Greece.

He qualified as a teacher of secondary education in 1968 and in 1970 the Academy awarded him the Benno Schotz Prize for Sculpture.

More Academy honours followed in the form of the Latimer Award in ’71, and the Gillies award in 1992.

In 2005 he was elected a Royal Scottish Academician – of which he was incredibly proud.

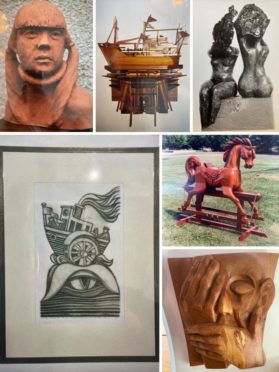

Commissions

No doubt influenced by life on the North-east coast and the woodworking skills of his father, Iain would receive commissions of his work across Scotland and beyond.

St Machar’s Cathedral in Aberdeen, Kinnaird Castle in Angus and the Glenfiddich Distillery to name a few.

His work can also be seen aboard an Arcadia Cruise Liner.

One commission, gave him more cause to smile than many others.

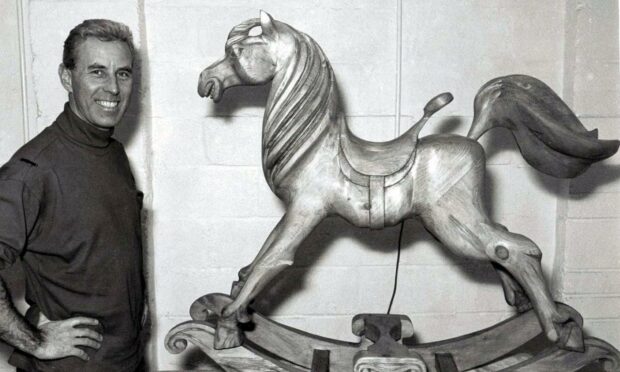

A rocking horse for Harrods

In his memoirs, entitled, ‘The Afterthought’ – Iain describes how he inadvertently became a supplier of Harrods.

He wrote: “As a carver, as a sculptor and as a father I had always hankered after making a rocking horse for my two daughters . So in 1985… in a typical fit of arrogance, decided that I would design and make the best rocking horses ever!”

He went on to say that by August Harrods had bought the first version.

He had to travel down to London to unpack it in the ‘cavernous’ storeroom under the shop. The Courier called it the ‘Rolls-Royce of Rocking Horses.’

He added: “By 1987 I had made and sold nine full-size rocking horses. One went to the daughter of a Royal Sheikh.”

Final days

Iain’s final art exhibition, Port to Port, was in 2016 but had since seen a deterioration in his health, developing a rare neuroma and vascular condition, as well as macular degeneration, making it difficult for him to work.

Daughter Sally Holland said: “Despite his ailments my dad was always in good form and I just spoken to him that week. Lockdowns meant we couldn’t see each other and so it was a devastating blow to find out he had Covid.

“His death was premature – there was so much more life in him yet.

“I’ll remember him for so much: for his humour, his work ethic, his devotion to his family. For being an incredible artist and a great man. I’m so, so proud to be his daughter and I miss him terribly.”

A celebration of his life took place in Edinburgh last month.