A simple car journey can be life-changing for the teens forced into couriering drugs for organised crime gangs.

Being arrested can lead to a moment of realisation that they need to escape the dark and dangerous world they’ve been lured into.

And for those tasked with safeguarding them, being able to speak to them during the journey to take them home can often provide the perfect opportunity to let them know help is available.

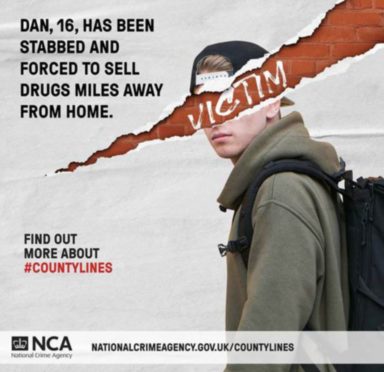

Children as young as 12 and 13 have been used in county lines activity often targeted and recruited by crime groups to deliver drugs across the UK – including the north and north-east.

Of the calls received, 22% of potential victims of criminal exploitation where drugs were involved were recorded as minors.

What happens to the children after they escape?

Modern Slavery Helpline manager, Rachel Harper explained that different cases go in different directions, saying that after arrest, youth offending teams run by local authorities would offer support to the young person.

There could be a diversion programme set up if the child is being prosecuted or charged to try and keep them out of jail, but also to try and find other routes for them.

Rachel said if it was clear the child was being used for county lines, they would recommend a local authority safeguarding team is informed as well as one from MSEH.

She said: “We would want to see that person as a child at risk and a victim. We would hope that the local authority is quickly looped in, and the child safeguarding team can come in and assess and work across agencies to really safeguard that child.”

There are some risk and prevention orders that are part of the modern slavery act which police can apply for.

Interviews can help pinpoint risk

Rachel said: “Those slavery trafficking risk orders can be a tailored way to safeguard a victim who is still in the vicinity of the gang and put some protection orders in place to keep them safe.”

The county line refers to the mobile phone used to take orders for drugs. A report from the National Crime Agency in 2018 said analysis suggested there were 2,000 so-called deal line numbers operated by criminal groups in the UK.

It also stated that a significant portion of county lines activity orginates in London, Merseyside and the west Midlands.

Measures taken in the north-east

Detective Inspector Lesley Clark from the North East Police Division’s public protection unit explained what happens when children who have been subject to county lines exploitation come to the attention of officers in this area.

If there are concerns about that child the public protection unit is contacted.

DI Clark said although the priority is child protection, if criminality is identified it is reported through the usual channels.

She said: “The key for the child or young person is getting them away from the risk, which is obviously the potential drug dealers that they are involved with.

“We’ll try and identify a place of safety. So if they are dealt with at a police office we’ll then be contacting the local force they are from, whether that’s Merseyside or Leeds or down in the West Midlands. We’ll be looking to see what concerns or risks they can share.”

Prevention is vital to keep child safe

Working in partnership with social work and other partners from the young person’s home area, police will then come up with a plan to return them.

Lesley said: “Once they are down there it would be down to the force there to implement what safety measures they need.

“The support that’s put in place comes from information sharing and making sure the home force knows exactly what the circumstances are, exactly what the risks are and the vulnerabilities we’ve identified.

“County lines is not just children travelling from English forces – it can be from the central belt or even children from our home area.”

She added: “The key is prevention, we don’t want that young person becoming involved in the exploitation again.”

‘The child bears the risk…they feel guilty’

Sarah said: “By the time a child is identified as being involved with county lines it’s incredibly difficult to intervene at that point.”

She stressed the importance of working along with missing people services, as a child going missing from their home is a sign something is wrong and could be a clue they are being drawn into something sinister.

Children are often unable to escape the clutches of the dealers because of accruing a drug debt, or being subject to threats or physical abuse.

Sarah said: “By then the stakes are so high. It’s easy to see them as making lifestyle choices, or as drug dealing low lives. But nothing can be further from the truth with some of these children.

“They have been drawn into a world that is so dark and so dangerous – they simply do not know what to do.

“That child continues to bear all the risk because they feel guilty for having got in so deep and they are trying to protect family members.”

‘An arrest can be a reachable moment’

While it can be difficult to intervene once a child has been caught, an arrest can sometimes provide a window of opportunity.

Sarah said: “It’s also true that something like a hospital admission or arrest is what we call a reachable moment. Just a moment where the child thinks ‘I can’t do this anymore, it’s too difficult, too dangerous’.”

She added: “There are things we can do there. We have had staff who have been to pick up a child perhaps from another local authority area or police force area.

“That car journey home, where you are not eyeball to eyeball and you can just have a conversation, can be a really important thing.

“Sometimes you can show them you understand and suggest there might be things and people who can help.”