Plans to revive forgotten railway stations around the north-east won’t just benefit rural residents, but could actually help save the planet.

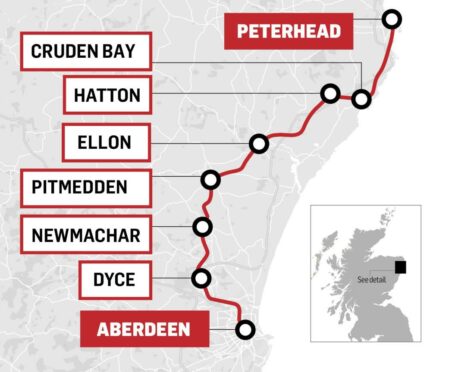

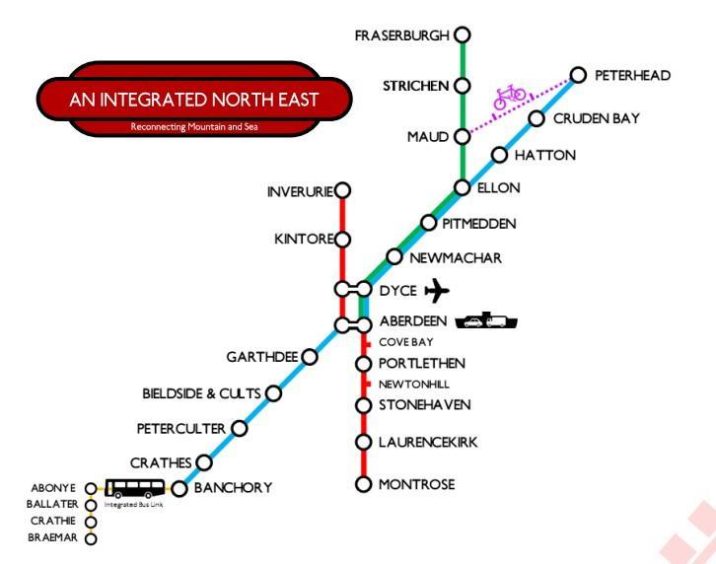

Earlier this year Campaign For North-East Rail (CNER) set out plans to bring modern infrastructure to the “forgotten” corners of Aberdeenshire, reopening rail links to Peterhead, Fraserburgh and Banchory.

Primarily the proposals look to offer a lifeline for what they call “isolated communities”. The Buchan towns of Peterhead and Fraserburgh have the dubious honour of being further from the British rail network than any other town in the UK.

But a new environmental report suggests that the impact of reintroducing rail links to the region wouldn’t just benefit residents and local businesses, but would also significantly contribute to saving the planet.

Step One: How to save 80 million miles of CO2

According to the group’s calculations, the railway could save at least 32,000 tonnes of carbon annually.

That is the equivalent of more than 80 million miles in an average car, or the carbon footprint of operating a UK university for six months.

We estimate that in its first year of operation the route would see over a million passengers, saving more than 450,000 trips on the A90 alone, and yet more on surrounding roads such as the A947. Additional trips will come with visitors to HMP Grampian, and in later years…

— Campaign for North East Rail (@CNERail) August 9, 2021

“Rail is a drastically more efficient way of moving heavy goods and, of course, passengers,” said Wyndham Williams, an engineer and one of the minds behind the CNER report.

“The main reason for that is from an engineering perspective. Frictional losses are so much lower – rails on a track are much more efficient than rubber tyres on a road – and the other main reason is that you can also stack up freight trains so they have 50 containers on them.

“Which means one locomotive is hauling the equivalent of 50 trucks with 50 diesel engines.”

Step Two: How did the Borders Railway do it?

Sitting down to crunch the numbers, the group applied strict parameters to their workings.

Together they analysed everything from vehicle statistics, regional tourism and oil and gas freight, to Brewdog beer shipments, fish tonnages and HMP & YOI Grampian visitor numbers.

These numbers were carefully measured and cross-checked before the group compared their findings to the Borders railway.

Opened in 2015, the Borders to Edinburgh railway line reconnected Galashiels and other local communities with Scotland’s capital by rail for the first time in 45 years.

With virtually the same length of track, the same number of stations and a similar population, the two railways have a lot in common.

“It’s been a blessing really that the Borders railway has been done,” said Mr Williams. “We don’t have to make guesses, we’ve actually got data, we’ve got passenger numbers, we’ve got costs.

“Peterhead and Galashiels are comparably sized places which are very similar in distance to the nearest big city, so we can lift this data and apply it to the north-east economy to make very reasonable assessments.”

Step Three: Rail freight is key

One of these assessments is that 450,000 trips will be shifted from private car to rail each year, but it’s not just passengers who will be reducing their CO2 contribution by taking the train.

Significant expansion of rail freight is a key ambition of the Scottish Government, precisely because of how much carbon can be saved shifting goods in this way.

Not only is less carbon released, but Mr Williams and others working on the campaign believe that long haul freight will be moved faster and more reliably on the proposed Buchan line, removing thousands of lorries from congested roads.

“Plus the route will be fully electrified from day one,” he said, referencing one of the Scottish Government’s other ongoing programmes, a zero-carbon railway by 2035.

“This means it will use 100% renewable fuel and no carbon would be generated from the journey at all, whether its freight or passenger.”

If they’re right, the numbers make for a compelling environmental case in favour of the proposed railway.

The investment and upheaval might seem huge from where we are standing now at the starting line but without big long-term projects like this which challenge the status quo, it’s difficult to see how Scotland will achieve its green targets.

“I was personally quite surprised by the numbers,” said Mr Williams. “I have never looked at anything like this before but the numbers are very compelling. There is a huge contribution to be made here.”