Aberdeen’s proposed low emission zone is unlikely to improve air quality in the city according to an air pollution expert – but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing.

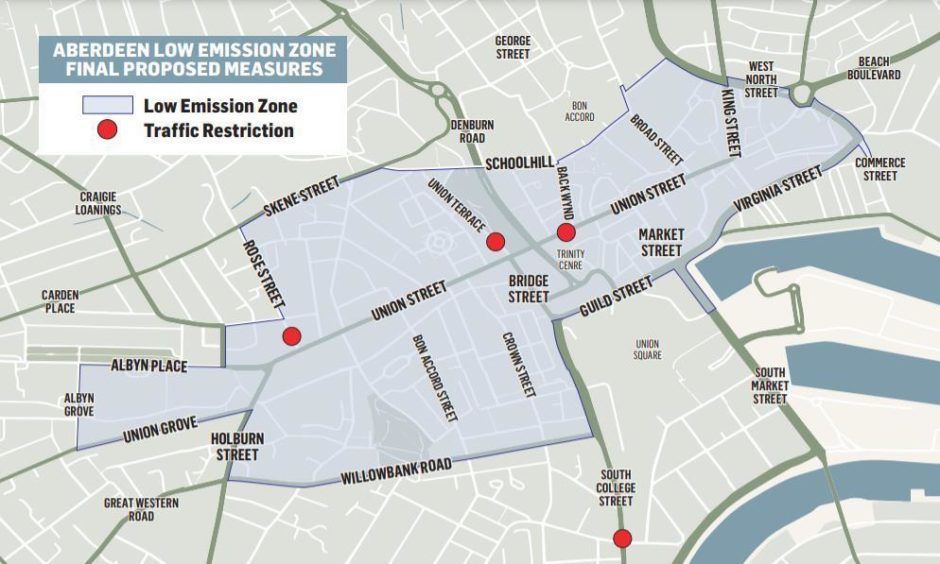

Improving air quality is one of the primary reasons laid out by the council to ban certain vehicles from driving on city centre roads from May 2022.

But an air quality expert – who spent two decades teaching at the University of Aberdeen – is concerned that in fact, air pollution levels in the city are unlikely to significantly change with the introduction of the proposed low emission zone (LEZ).

Why won’t the LEZ automatically improve air quality?

Professor Sean Semple has studied our air for most of his career, particularly focusing on researching the health effects of air pollution.

He is uneasy with the emphasis being put on the LEZ’s ability to reduce air pollution and resolve associated health problems.

“While I think measures to help reduce car use in Aberdeen to limit CO2 emissions are very welcome, I’m wary of the focus being on improving air quality just in terms of PM2.5 (tiny inhalable particles of pollution) or nitrogen oxides (gases released from burning fossil fuels),” he said.

He points out that a widely recognised issue with low emission zones is that they can increase traffic in areas around the periphery of the restrictions, as cars are forced on longer, convoluted routes to avoid certain streets.

“It is also worth remembering that emissions from ships burning heavy fuel oil in Aberdeen harbour are likely to contribute substantially to levels of PM2.5 in the centre of the city,” he said.

Is Aberdeen’s air quality really that bad?

Historically much of the smog and air pollution in the UK came from vehicles, industry and coal fires.

This has changed with the decline of heavy industry and with the development of cleaner car engines. And although we tend to think our air quality is getting worse, data shows that our air is much cleaner now than it was 100 years ago.

Professor Semple says that the north-east of Scotland in particular now has some of the cleanest and “best quality” air in the world. Levels of PM2.5 are about ten times lower than cities like Delhi.

But comparing Aberdeen to an Indian city of nearly 20 million people isn’t exactly looking at like for like.

Nonetheless air quality in Aberdeen and across Scotland’s cities remains a concern. Last year was the first time in a decade that the country was within the legal air pollution limit and it doesn’t take a genius to work out why.

Lockdown instructions to stay at home meant that businesses across the country shut down overnight. Traffic plummeted, and with it, air pollution levels dropped too.

Official data shows that the first two months of lockdown in 2020 were enough to slash annual average levels of air pollution, meaning that no sites breached the legal limits for the first time since their introduction in 2010.

What harm can air pollution cause?

There is increasing evidence that air pollution impacts our health.

Since the 1950s Professor Semple says we have known that periods of poor outdoor air quality increase mortality, simply that the number of deaths increases immediately after days when pollutant levels are high.

Deaths only occur in fairly extreme cases, but other day-to-day issues can be exacerbated by pollution.

“We know that pollution impacts on cardiovascular health,” said Professor Semple. “Heart attacks and strokes also increase when air pollution is high.

“More recently there have been studies suggesting that pollution may be linked to reduced immunity, with studies showing that cells in our lungs that are exposed to fine particles from traffic may be more susceptible to bacterial infection.”

Kids can be particularly at risk.

“Their lungs and airways are developing and so any impacts can be lifelong,” said the professor.

Can indoor air quality be worse than outdoor?

Professor Semple has a curveball up his sleeve. While we fuss over the LEZ and roadside air quality data, he explains that indoor air quality can be as bad as, if not worse than, outdoor.

“Much of the science has focused on air pollution outdoors – probably because it is easier to measure and easier to carry out studies examining outdoor levels with effects on the population being studied,” he said.

But what’s going on at home is equally important, considering we spend 90% of our time indoors.

He explains that indoor sources of pollution can come from seemingly innocent sources. “Cooking, particularly frying and roasting food, can produce high levels of particles,” he said. “Other sources can include wood stoves, candles and smoking. Smoking at home produces extremely high concentrations of harmful fine particles.”

It’s probably of no surprise to most people that when Professor Semple lead a research group measuring the fine PM2.5 particles in homes across Scotland, they found that in those where someone smokes the average daily concentrations of PM2.5 were many times higher than the levels measured next to the busiest roads in Glasgow, Aberdeen or Edinburgh.

“The current scientific thinking is that the fine particles from any source, be it traffic or cigarette smoke or cooking, is equally bad for health,” he concluded.

So while the LEZ may be a positive step for the environment in reducing the number of heavily polluting cars pumping out CO2 in our city centre, whether it is a mechanism to truly improve air quality in the city remains to be seen.